![]()

Chapter 1

A Spanish Prince and an English Princess

It has pleased Our Lord to deliver the Empress, my very dear and very beloved wife. Today, Tuesday the twenty-first of the present month, she gave birth to a son. I hope in God that he will prove to be of service for you and for the great good of these kingdoms.

Charles V

At a little after four in the afternoon, while the rain came down in torrents, the bells of the church of San Pablo de Valladolid started ringing wildly. At the signal other bells in the city joined one by one. Across the narrow street in the great house of Bernardino Pimentel, the young Empress Isabel had just given birth to a son. The new father, Emperor Charles V, waited just long enough to hold the baby in his arms, then handed him back to the nurse. With his whole court Charles then marched through a temporary wooden passageway connecting the house to the church of San Pablo, where the choir monks sang a Te Deum. Once the service ended, the emperor signed a proclamation addressed to each of the cities of Castile, announcing the royal birth: “It has pleased Our Lord to deliver the Empress, my very dear and very beloved wife. Today, Tuesday the twenty-first of the present month, she gave birth to a son. I hope in God that he will prove to be of service for you and for the great good of these kingdoms. I pray to Him that it may be so and that I may better serve you, as this is what I have longed for.”1

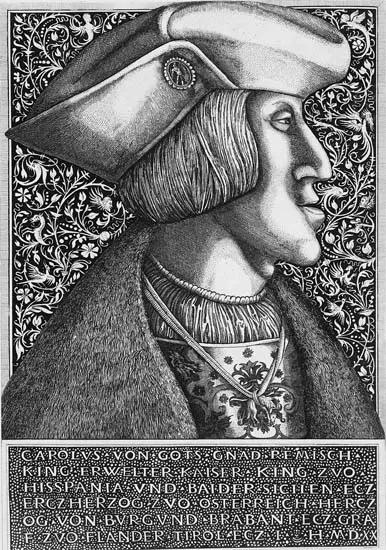

The date was 21 May 1527. Just ten years earlier, when Charles first arrived in Valladolid, he was a stranger, speaking little and understanding less of the Castilian tongue. Born and raised in the Netherlands, Charles was an outsider in Spain, unwelcome in the country he had come to rule. Though scarcely seventeen years of age, he was already ruler of the Netherlands, Duke of Burgundy, and Archduke of Austria, all titles inherited from his father, Philip the Handsome. The thrones of Spain were his by inheritance from his grandfather, Ferdinand of Aragon; but he was a foreigner, and the Spanish nobility was reluctant to welcome him. In fact, they preferred his younger brother Ferdinand, who had been born and raised in Spain, knew the language, and understood all the local ways. Perhaps worst of all, Charles brought with him a full complement of Flemish supporters, who proceeded to grab the most lucrative offices in church and government. Spanish discontent became so severe that the Cortes de Castilla finally presented Charles with a list of eighty-eight demands, including these: get married and produce a Castilian heir to the throne; stop appointing foreigners to office; and learn the Castillian language in order to speak to people and understand what they have to say. To this last Charles replied: “We will try very hard to do it.”2

Discontent grew during the next year, and reached a peak when Charles left the country to take up the imperial crown. Then a general revolt swept the towns of Castile, not finally suppressed for another two years. When Charles returned, he imprisoned some of the remaining offenders, executed the worst, and pardoned the rest.3

Midst all the turmoil of ruling the Netherlands and the Holy Roman Empire, Charles worked very hard to keep his promise to the cortes. He learned the language of Castile, gave key appointments to local people, married, and produced an heir. It took a decade, but Charles finally became undisputed ruler, and Philip was his heir. There were grand celebrations in Valladolid and elsewhere, when the little prince was baptized on 5 June 1527 in a wonderful ceremony at the church of San Pablo.4

Fig. 1 Charles, King of Spain, in 1521

A story, passed through the Dormer family of England, gives some insight into the religious rivalries in Valladolid, as well as the Spanish royal baptismal protocol. The royal rooms were in the house of Bernardino Pimentel. This grand structure lay next to the plaza that fronted the great church of San Pablo. The main gate of this dwelling faced toward a Dominican convent, a smaller church in a less prestigious parish. However, a tall window in the royal suite faced the plaza of San Pablo, and it became the door of a special passageway built to connect the house and the church. Suitably decorated for the occasion, the temporary hallway brought the baptismal procession to the church, without the need to enter the confines of the other parish. The little prince was carried in the arms of Don Iñigo de Velasco, condestable de Castilla and duque de Béjar, who was godfather. He was accompanied by the emperor’s sister, Leonora, widowed Queen of Portugal and Queen of France, who was godmother. At the door of the church the entourage was met by Alonso de Fonseca, archbishop of Toledo, along with other bishops and dignitaries. Following an ancient formula, these worthies asked the godparents what they wanted. Answering for the prince, they replied that they wanted baptism. The archbishop then proceeded with the ceremony, during which the infant cried, as infants are wont to do. Afterwards the King of Arms introduced the new heir by three times proclaiming him: “Don Felipe por la gracia de Dios, Príncipe de Spaña.” After a solemn Te Deum the royal entourage returned to the house of Bernardino Pimentel, and the infant prince went back to bed.5

Meanwhile in England a young princess, a distant relation of the Spanish heir, suddenly found court life much less congenial than it had been. Born on 18 February 1516, Mary was the child of Henry VIII of England and his wife Katherine of Aragon.

Henry expected his wife to produce a male child to inherit his throne. During the first decade of their marriage Katherine was pregnant at least six times, producing both boys and girls, but Mary was the only one who survived infancy. Thus Mary was heir to the throne of England. She was a pretty little girl, and Henry loved her. But she was not the son that Henry wanted as his heir, so Mary often suffered from her father’s cold indifference.

While Mary was still a child Henry began to use her as pawn in international diplomacy. At the age of two she was promised to the heir to the throne of France, at the age of six to Charles himself, who was her cousin, and at the age of nine to a younger son of the French king.6

When they were first married, Katherine was certainly a pretty girl, but her beauty faded as time passed. In any case, Henry was never inclined to be a faithful husband, and his ever-roving eye lit upon a succession of mistresses and temporary lovers. One of the young ladies actually produced a son, who was christened Henry and supplied with the honorific Fitzroy. When it became more and more likely that Katherine would not bear a son, Henry began to treat the boy as though he might possibly inherit the throne, leaving Katherine and Mary to brood in isolation. On the other hand, the mother of young Henry Fitzroy found herself abandoned for a new prospect who had caught the king’s fancy. This young woman, Anne Boleyn, keeping in mind the fate of her predecessors, made it plain to the king that she wanted a husband and not just a lover. Henry, for his part, began to think that if he married Anne, she might be able to give him a legitimate son. Therefore, he determined to end his marriage to Katherine.7

As a Catholic, Henry could not divorce his wife, but if their marriage were invalid, he was free to marry Anne. Henry began to think the marriage to Katherine was invalid. As a young girl Katherine had been married to Henry’s older brother Arthur. However, Arthur died at the age of fifteen, and Katherine then married Henry. So there was his solution: if Katherine’s earlier marriage to her husband’s brother had been consummated, then by canon law there was a relationship of affinity between them, and they could not marry. At the time their marriage was arranged the problem did not seem to be insurmountable, for Katherine swore that she was still a virgin (and Henry later boasted that this was indeed true). But just to be on the safe side, Henry’s negotiators secured a papal dispensation for affinity before the wedding took place. It was a small point, but there was another, less serious and equally obscure: the canonical impediment of “public honesty,” arising from the fact that a previous marriage had been contracted. This was not considered a problem at the time, and the marriage negotiators seemingly considered that it was unnecessary for the dispensation to cover that point.8

Fig. 2 Katherine of Aragon

Eighteen years later, increasingly anxious to take Anne Boleyn to his bed, Henry said that these and other matters made him doubt the validity of the papal dispensation. Gathering his expert theologians and canon lawyers Henry began to say that Katherine had not come to him as a virgin and that in any case the papal dispensation was insufficient to overcome the various difficulties. Then Henry introduced a novel argument. He claimed that a verse in Leviticus forbade him to marry his brother’s wife: “And if a man shall take his brother’s wife, it is an unclean thing: he hath uncovered his brother’s nakedness; they shall be childless.”9 On its face, this was a weak argument, based on a verse of scripture that was ambiguous at best,10 for Katherine was not a wife but a widow. And other verses in scripture, cited in the annulment of Katherine’s marriage to Arthur, seemed to encourage marriage with a brother’s widow.11 It is not clear why Henry chose this verse as the basis for his appeal.

In the end, the pope refused to annul the marriage between Henry and Katherine. Thereupon, in some haste, Henry married Anne, and got a new archbishop to annul his marriage to Katherine. In the course of events Katherine was deprived of her royal status, and Mary was declared illegitimate, no longer eligible for succession to the throne.12 Within a few months the new queen gave birth to a girl, Elizabeth. Though disappointed again in trying to produce a son, Henry had little choice but to welcome Elizabeth as the new heir to the throne.

The pope responded to all this with a bull of excommunication against the English king. Henry then had Parliament declare that the king was supreme head of the Church of England. Thus, with a few rash moves Henry managed to reject and humiliate both Mary and her mother, in the process alienating himself from most of Catholic Europe and plunging England into more than a century of turmoil.

It was a period of agony for Mary, who was barely in her teens when Henry began living openly with Anne.13 Childhood for a royal heir was never uninterrupted bliss, but Mary’s youth was more troubled than most. Separated from the loving care of her mother, and denied the attention of her father, she became morose and disillusioned. Kept away from the court, she was never able to observe how the country was governed. Instead, she learned that courts were places of favoritism and intrigue, a useful lesson, but not sufficient training for a future queen.

In fact, Mary was not educated to become a ruling queen. Rather, she was taught to develop her mind in such a way as to strengthen her practice of the virtues of chastity and charity, the chief marks of a good woman. Governing was best left in the hands of men. Mary was trained only to be a good wife for a king and a good mother for a prince.14 From time to time there was talk that she might inherit the throne, perhaps allowing her husband to do the work of governing, but by the time she was twenty this seemed to her like a distant possibility. She had sufficient grace and charm that various lesser princes sought her hand. But nothing came of these negotiations, and Mary began to realize that Henry would never allow her to marry. The reasons were not hard to find: a foreign match would bring with it the threat of invasion and foreign rule, while a marriage at home might well split the kingdom between rival claimants to the throne.15

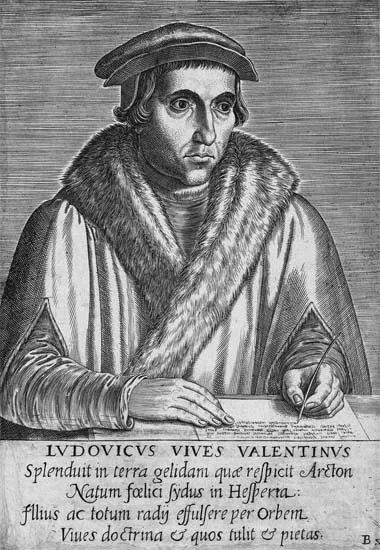

When the time came to begin Mary’s formal education, the choice of a tutor was left in Katherine’s hands. Even though there were scholars of great stature in England, Katherine looked abroad for help. With some prompting from Sir Thomas More she became the friend and patroness of Juan Luis Vives, a Spanish humanist teaching at the University of Louvain. In 1521 Vives had completed a study of Augustine’s City of God and dedicated it to Henry VIII. Very soon thereafter, with some prompting from More, Henry made a small annual grant to Vives. The new pension arrived just in the nick of time for Vives, who had lost his patron at Bruges.16 A little later Vives completed a new book, De institutione fœminæ Christianæ, and dedicated the work to Katherine, suggesting that it be used in directing the study of the young princess.17 This was not just gratitude on the part of Vives. He hoped that the dedication would move the queen to increase his stipend and invite him to stay in England.

Fig. 3 Juan Luis Vives, Mary’s tutor

England, 1523, Mary’s education

By this time Mary was seven years old. Vives wrote in his book that a child should start reading somewhere between the ages of four and seven. If his words were framed to fit the little princess, as they probably were, then Mary may already have begun to read. At the same time, her mother was very likely showing Mary how to spin and sew and to perform other domestic duties. Katherine herself had learned these skills from her own mother, Isabel, and Vives said that such work was as fit for “a pri[n]cesse or a quene” as for any other woman.18

So what was the point of learning for a woman? In the mind of Vives, Mary could have no better example than the three daughters of Thomas More. Their father had considered learning as the foundation of goodness and chastity. Mary should not just learn “uoyd uerses, nor wanton or triflynge songes, but some sad sentence, prudent and chaste, taken out of holy scripture, or the s...