![]()

— Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

original title: Per un Pugno di Dollari

Credits

DIRECTOR – ‘Bob Robertson’ (Sergio Leone)

PRODUCERS – ‘Harry Colombo’ (Arrigo Colombo) and ‘George Papi’ (Giorgio Papi)

SCREENPLAY – Sergio Leone, Duccio Tessari, Jaime Comas, Fernando Di Leo, Tonino Valerii and Victor A. Catena

DIALOGUE – Mark Lowell and Clint Eastwood

ART DIRECTOR, SET DECORATOR AND COSTUMES – ‘Charles Simons’ (Carlo Simi)

EDITING – ‘Bob Quintle’ (Roberto Cinquini)

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY – ‘Jack Dalmas’ (Massimo Dallamano)

MUSIC – ‘Dan Savio’ (Ennio Morricone)

Interiors filmed at Cinecitta Film Studios, Rome

Techniscope/Technicolor

An Italian/Spanish/West German co-production.

Jolly Film (Rome)/Ocean Film (Madrid)/Constantin Film (Munich)

Released internationally by United Artists

Cast

Clint Eastwood (Joe, the Stranger); Marianne Koch (Marisol); ‘Johnny Wells’, Gian Maria Volonte (Ramon Rojo); ‘W. Lukschy’, Wolfgang Lukschy (Sheriff John Baxter); ‘S.Rupp’, Sieghardt Rupp (Esteban Rojo); ‘Joe Edger’, Josef Egger (Piripero); Antonio Prieto (Don Miguel Rojo); Margherita Lozano (Consuela Baxter); ‘Pepe Calvo’, Jose Calvo (Silvanito); Daniel Martin (Julio); Fredy Arco (Jesus); ‘Carol Brown’, Bruno Carotenuto (Antonio Baxter); ‘Benny Reeves’, Benito Stefanelli (Rubio); ‘Richard Stuyvesant’, Mario Brega (Chico); Jose Canalejas (Alvaro); ‘Aldo Sambreli’, Aldo Sambrell (Manolo); Umberto Spadaro (Miguel); Jose Riesgo (Mexican Cavalry captain); Jose Halufi, Nazzareno Natale and Fernando Sanchez Polack (members of Rojo gang); Bill Thompkins, Joe Kamel, Luis Barboo, Julio Perez Taberno, Antonio Molino Rojo, Franciso Braña, Antonio Pico and Lorenzo Robledo (members of Baxter gang) with Raf Baldassare, Manuel Peña, Jose Orjas, Juan Cortes and Antonio Moreno

Though the westerns made by Sergio Leone and Clint Eastwood in the mid-sixties are forever called spaghetti westerns, the Spanish contribution to the genre has often been ignored. The German-made, Yugoslav-shot ‘Winnetou’ stories may have awakened European producers’ interest in westerns, but Leone’s movies would have looked very different if they hadn’t been shot in the beautiful locations around Madrid and the deserts and sierras of Almeria. Among the expatriate American actors who found themselves sweating in temperatures that topped 110 degrees in the summer, Almeria was affectionately known as the ‘Armpit of Europe’. This sandblasted landscape had a reputation as a place where washed-up ‘stars’ went to die in the cheapest international adventure co-productions. But no one in Spain could have foreseen the impact Leone was about to have on their film industry when the director arrived there in spring 1964 with an actor dressed in a blanket.

The Spanish had been making westerns since 1962, often co-producing with the French. These exotic action movies were based on the Zorro legend. Whilst not being particularly popular outside Spain, they did prove two things: Spain could look passably ‘western’ and stories with a Hispanic flavour could be made cheaply on their own doorstep. The handful of Zorro films made in the early sixties are interesting period pieces. The heroes are highly camp, the villains surprisingly brutal and the quick-fire action ensures they are nothing less than entertaining. Frank Latimore often played Don Jose de la Torre (a.k.a. ‘El Zorro’ – ‘The Fox’). Most interesting is the friction between the local gringos and Mexicans, which is at the heart of the original Zorro stories. The villains are usually gringo, but the treachery and murder that escalates the violent situation in ‘Old California’ has clear parallels with the Italian westerns that followed in their wake.

Sergio Leone had spent the late fifties assisting Hollywood film-makers on Rome-shot epics. Since then, his only steady work had been to collaborate on screenplays with other budding directors, like Duccio Tessari, Sergio Corbucci and Sergio Sollima. Among his assignments was some second-unit work on the chariot race in Ben Hur (1959), though to hear Leone tell the tale you would think he had driven the chariots. Leone then directed The Last Days of Pompeii (1959) and The Colossus of Rhodes (1960), both reasonable successes. Soon afterwards he was fired from the second unit of The Last Days of Sodom and Gomorrah (1962) for taking excessively long lunch breaks. Temporarily unemployed, Leone wrote a western provisionally entitled The Magnificent Stranger (released as A Fistful of Dollars), collaborating with Jaime Comas, Victor Catena, Tonino Valerii, Duccio Tessari and Fernando Di Leo. There is no writing credit at the beginning of the film, only ‘Dialogue by Mark Lowell’ (the English translator). Some sources mention a writer named ‘G.Schock’, which was a Germanic-sounding pseudonym for the writers, to please the West German investors. Interestingly, the name ‘Jaime Comas’ appears on a gravestone in the finished film.

The plot of Leone’s film was inspired by Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961), which was released in Italy as La Sfida Del Samurai (‘The Challenge of the Samurai’). In Yojimbo, a nameless ronin (played by Toshiro Mifune) arrives in a shantytown ruled by two rival families. The factions’ business interests are different (one sells saki, the other silk), but both want control of the area. By skilful manipulation, the yojimbo (‘bodyguard’) hires himself to each gang until the conflict is resolved with both groups being annihilated, leaving the wanderer to move on. Kurosawa’s movie is a comic strip version of his earlier, more serious works, injecting sidelong humour and humanitarian observations into a jokey, hokey but nevertheless brutal narrative. Leone retained all the major characters intact, adapting them to a ‘westernised’ (as in ‘wild west’) version of the Japanese prototypes. In A Fistful of Dollars, Gonji (the tavernkeeper) became Silvanito; Hansuke (the watchman) became Juan De Dios (the bellringer); Kuma (the coffin-maker) became Piripero and the nameless ronin became a nameless gunfighter.

In Leone’s adaptation, the gangs in the Mexican village of San Miguel are distinguished as Gringo and Mexican (like the Zorro films), but are still two families – gunrunning Sheriff John Baxter (a weak-willed lawman), his wife Consuela (who really runs the show) and their slow-witted son Antonio, against a trio of Mexican brothers: the liquor-selling Rojos. Although the eldest of the Rojos is named Don Miguel (or Benito in the Italian version), he wields no power in the clan, which is led by his sadistic brother, Ramon. The stranger tells Silvanito, ‘The Baxters over there, the Rojos there and me right in the middle. Crazy bellringer was right, there’s money to be made in a place like this.’ The stranger plays both ends against the middle, intensifying the rivalry, until in the finale the Rojos massacre the Baxters. A problem with a ‘westernised’ version of Yojimbo was that the original final showdown pitted the hero, armed with a sword and a throwing knife, against the villain Unosuke (Tatsuya Nakadai) with his pistol – the only firearm in town. Leone’s adaptation pits the stranger, with his Colt .45 and a piece of railcar strapped to his chest, against Ramon’s Winchester 73 carbine, with its greater range and chamber capacity; but again the inferior weapon prevails.

The main differences between Yojimbo and Fistful are the motives, characters and scenes added by Leone. The hero siding with the bad guys in order to destroy them owes much to the ‘Zorro’ movies, while gunrunners and liquor merchants were a regular ingredient of early Italian/Spanish cowboy and Indian fare. A gold robbery and the stranger’s location of the loot during a cemetery shootout (a detective story element) was suggested by the adventures of the Continental Op in Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest (called Piombo e Sangue or ‘Lead and Blood’ in Italy) and the western-set Corkscrew. Both these stories feature a lone hero caught in a faction-riven town. Hammett was best known for his tough, precise style that pared every detail to the minimum; in Hammett’s world, the rule of thumb was ‘trust no one’, and Kurosawa’s hero seemed to agree. Interestingly, in spring 1962, an article in Film Quarterly titled ‘When the Twain Meet: Hollywood’s Remake of The Seven Samurai’ (which compared Kurosawa’s original with John Sturges’s The Magnificent Seven) closed with news that ‘a minor United Artists producer’ was soon to remake Yojimbo in the US as a western, but the film never happened.

By 1964, Leone had convinced Jolly Film (Italy), Constantin Film (West Germany) and Ocean Film (Spain) to put up $200,000 to make a film provisionally entitled The Magnificent Stranger. He wanted Henry Fonda as the stranger, but Fonda was far too big a star. The title of the film was clearly based on The Magnificent Seven (or I Magnifici Sette on its Italian release), so Leone approached two of the Seven stars: Charles Bronson judged the script the worst he had ever read and James Coburn was too expensive (wanting $25,000 when only $15,000 was available). Rory Calhoun (the star of The Colossus of Rhodes) also turned Leone down. Folklore has it that Richard Harrison, an ex-AIP actor working at Cinecitta, suggested Leone should try Clint Eastwood. The story is fanciful, but however Leone found Eastwood it was a happy accident. Previously reduced to earning a living digging swimming pools and as a lifeguard, Eastwood’s screen career began in the fifties, on contract at Universal. He played the pilot who napalmed the giant Tarantula (1953) and also appeared in ‘the lousiest Western ever made’ (Ambush at Cimarron Pass – 1957). He was currently playing Rowdy Yates in the CBS TV series, Rawhide.

Leone watched an episode of Rawhide entitled ‘Incident of the Black Sheep’, wherein Rowdy escorts an injured sheep farmer (guest star Richard Baseheart) and his flock to a nearby town and suffers the same prejudicial treatment that he, as a cattleman, had meted out on the sheepherder. Leone thought that six-foot-four-inch Eastwood stole every scene, with his laid-back acting style. Eastwood wasn’t enthusiastic about a remake of a Japanese action film near Madrid, but his wife Maggie thought it was ‘wild’ and ‘interesting’. Eastwood found the script unintentionally funny as it was written in a strange version of American slang. But the fee was attractive, as was the trip to Europe (somewhere he’d never been) and so he agreed, providing he could alter his dialogue. Moreover, once his dialogue was pruned, $15,000 wasn’t a bad salary for standing, squinting into the sun in Spain. Even so, the fact that he was the cheapest actor available for the role wasn’t lost on Eastwood – especially when Leone had the stranger telling Don Miguel ‘I don’t work cheap’.

Eastwood had seen Yojimbo and saw in Mifune a very different acting style – a strength of character through silence, coupled with a dynamism in the action sequences. He realised that such a scruffy, stubbled style would be well suited to a new kind of antihero. Eastwood had experimented with his character to a certain extent on Rawhide, even adopting his soon-to-be trademark stubble in episodes such as ‘Incident of the Phantom Bugler’. But after five years on the series he was sick of his clean-cut image, exemplified by a series of health tips in TV Guide. He was equally tired of the thin plot material and the lack of scope in Rowdy’s character. He claimed that his costume on Rawhide ‘stood up by itself’ and out of boredom he would put lip-gloss on his horse to liven up the monotony. It was clear that it was time for a change of scenery.

Covering all markets, the multinational production companies behind Fistful bankrolled a cosmopolitan cast of German and Italian co-stars and Spanish extras. German actors Wolfgang Lukschy, Sieghardt Rupp and Josef Egger are all higher in the credits than Spaniard Pepe Calvo, due to the West German backing for the film. Lukschy was Colonel-General Alfred Jodl in The Longest Day (1962) and the German-dubbed voice of John Wayne and Gary Cooper. Though German actress Marianne Koch speaks only in three scenes and sings in another, she gets second billing, for what amounts to a cameo role as Marisol, a Mexican peasant woman with jet-black hair and Cleopatra eyeliner. Koch was a popular actress in Europe at the time, occasionally appearing in British and West German thrillers and jungle adventures. She often adopted the pseudonym ‘Marianne Cook’, though some of the early advertising material for Fistful in Italy christened her ‘Marianne Kock’.

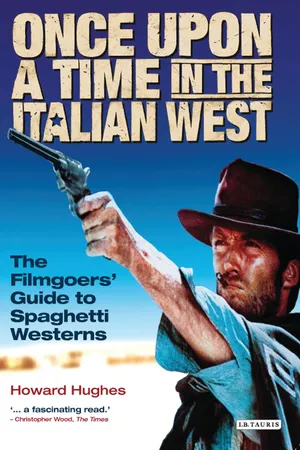

The Stranger in town (Clint Eastwood) and Silvanito the bartender (Pepe Calvo) in familiar surroundings. Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

Italian Gian Maria Volonte (cast as Ramon Rojo) was billed as ‘Johnny Wells’ in the titles, ‘John Wels’ on posters and ‘Johannes Siedel’ in Germany. Thirty-one-year-old Volonte was a stage actor who toured from the age of 22 with an actors’ caravan around Italy, playing the classics. His fiery temper left him banned in Italy after an argument over a production of Crime and Punishment, so he finished up in genre movies like Hercules Conquers Atlantis (1961) and Journey Beneath the Desert (1961). Margherita Lozano had appeared in Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana (1961), while both Antonio Prieto and Daniel Martin had appeared in an interesting Spanish film, Los Tarantos (1964), which detailed a tragic love affair between youngsters from rival gypsy families. It was Fistful that formed Leone’s stock company of actors, and Benito Stefanelli, Mario Brega, Antonio Molino Rojo, Lorenzo Robledo and Aldo Sambrell all appeared in Leone’s later westerns. Stefanelli also supervised the stunt work and was a translator.

Eastwood and his stunt-double Bill Thompkins arrived for the 11-week shooting schedule (from late April to June 1964). Some sources claim that Eastwood was also billed as ‘Western Consultant’, but it is Thompkins (billed by his full name, W.R.Thompkins) who is credited as ‘Technical Adviser’. He also had a bit part in the film (he’s the Baxter gunman in the green shirt) and did Eastwood’s nighttime riding scenes, shot by the second unit in Almeria. The low-budget production was a world away from Hollywood. There were pay strikes, faulty power generators and no sanitary facilities. According to Leone’s assistant, Tonino Valerii, the rental on the western town set still hadn’t been paid months after the film was completed. Eastwood was amazed at the Italians’ lack of western knowledge, pointing out that coonskin hats weren’t suitable for a Mexican setting. While on location, Leone spotted a tree he thought would be perfect for the hanging tree at the beginning of the film, so the tree was dug up and relocated.

The San Miguel town set was the Hojo De Manzanares ‘western village’ near Colmenar Viejo, north of Madrid. The large adobe church was converted into the wooden Baxter house. At the opposite end of the street, a false front was superimposed on an existing saloon building to become the Mexican Rojo residence, with a fake wall and gateway erected to make the property look like a hacienda. Franco Giraldi was Leone’s second unit director, and he later used the town set for Seven Guns for the MacGregors (1965), in the scene where the water tower in the main street was blown up for the finale. It is interesting to see how other directors used the same set. In Minnesota Clay (1964), Left-handed Johnny West (1965) and In a Colt’s Shadow (1966), the street is bustling with market stalls and locals going about their daily business, whereas in Fistful it is deserted. The graveyard was near the town set, while the Rio Bravo river (where Ramon’s gang attack a Mexican Army convoy) was at Aldea Del Fresno (the ‘Village of the Ash Trees’) on the River Alberche. The desert riding sequences were shot in Almeria; the house where peasant girl Marisol was imprisoned by the Rojos still stands in San Jose – it is now a hotel called El Sotillo. The stranger’s ride into the outskirts of San Miguel was filmed in the Spanish village of Los Albaricoques. Other sets, costumes and props were from the Zorro movies. A mine, where Zorro undergoes his ‘transformation’, reappears as the stranger’s hideout. The bullet-ridden suits of conquistador armour that decorate the Rojo’s house had once adorned the Californian governor’s residence, while the Mexican courtyard and interiors were part of Casa De Campo, a rural museum in Madrid already used as a marketplace in Zorro the Avenger (1962).

The sunny locations are beautifully photographed by Massimo Dallamano. Unfortunately, some of the evening scenes are filmed day-for-night using filters. This is understandable on the low budget, but they cheapen Fistful’s look. Where filters were not used, the night scenes were more stylish, with Dallamano using torches and firelight to good effect. When the stranger is introduced to Ramon in a sunny courtyard, pieces of white fluff float across the scene, giving an arty, parad...