![]()

CHAPTER 1

America before Pearl Harbor: ostrich or owl?

In the years before Pearl Harbor, many Americans were in furious disagreement over whether or not to resist Hitler; a disagreement that continued earlier arguments over participation in World War I and the League of Nations. From 1920 until 1932, successive Republican Presidents pursued a policy of keeping America isolated from international organizations and conflict. In contrast, Roosevelt, elected President in 1932, had supported President Woodrow Wilson and the League of Nations. He introduced policies of free trade and tried to use economic and military means to counter what he saw as the growing threat from Hitler and Mussolini, and the Japanese in Asia. To persuade Americans to get involved abroad, he put forward a positive agenda of international cooperation as values for which Americans should be prepared to stand up for. After Pearl Harbor they were formalized in the Declaration by United Nations.

One reason the ideas of the United Nations during the war have been forgotten is that as US politics became more conservative during the Cold War when Roosevelt’s liberal policies were attacked successfully. As part of this process, the liberal political ideas he had used to underpin the war effort were discarded. In life, Roosevelt defeated conservative resistance to a radical internationalist policy. In death, the conservative ascendancy has seen his role in the war effort marginalized along with the ideas he championed.

From 1946 his face has been on US ten cent coins. Nevertheless, he has been neglected by the US military. One might expect that, given his track record in leading what Americans now call ‘the Greatest Generation’, Roosevelt would be revered by America’s national security institutions as a strategic genius. Indeed, he built most of the military, industrial and bureaucratic organizations that are so influential today, as the historian Alan Henrikson (2008) has demonstrated.

Nevertheless, there are no significant US Army, Air Force or Marine Corps facilities that bear Roosevelt’s name. And he has only one of the US Navy’s smallest ships named in his honour, while Gerald Ford, President for just two years, has a new generation of aircraft carriers, the most prestigious type of warship, named after him. Only in the 1990s was a major memorial built for Roosevelt in Washington, DC, and this seems to have been an isolated act.

Certainly, conservatives who associate themselves with the aura of victory over Hitler, and opposition to anything they can call appeasement, do not mention him, or the policies he led, in favourable terms, despite his leadership in opposing appeasement. President George W. Bush used the ‘Axis of Evil’ terminology as a means of comparing Iran, Iraq and North Korea to Hitler and his Axis allies,1 without any mention of the President who led the resistance to Hitler. The ostensible reason for neglecting Roosevelt as a military leader is his alleged appeasement of Stalin. Whatever the reality, this should not detract from his greatest success, the defeat of Hitler, Mussolini and the Japanese warlords.

Roosevelt himself regarded these critics of his policy towards Stalin as part of a general smear campaign. However, as we shall see, Roosevelt’s success in mobilizing America required him to defeat conservative ‘anti-communist’ smears within the United States in the 1920s and 1930s and throughout the war. As Roosevelt put it, ‘Labor-baiters, bigots, and some politicians use the term “Communism” loosely, and apply it to every progressive social measure and to the views of every foreign-born citizen with whom they disagree’2 – a practice still familiar almost a century later.

Roosevelt brought to politics a strand of progressive Protestant values of part of the New England elite. These included a belief in public service and helping the unfortunate in society instilled in him by Endicott Peabody, his headmaster at Groton School. These ideas were suited to an age when economic disaster afflicted many Americans. When he became President he had already the experience of high office as Navy Secretary in World War I and as Governor of New York. He had also had to steel himself to overcome an inability to walk caused by the disease poliomyelitis.

Roosevelt gave his own assessment of the political struggle up to Pearl Harbor in a speech he gave in 1944 when victory in World War II was in sight.3 In a radio broadcast made before 2,000 people at the Foreign Policy Association in Manhattan, Roosevelt reminded his listeners that it was the Republican Party that had opposed the League of Nations, so dooming that organization. He accused the Republicans in Congress of obstructing his efforts to prevent the rise of Hitler and warned that if they were returned to power they would destroy his efforts at building the peace. And he particularly attacked their past refusal to recognize the existence of the Soviet Union.

I The expansion of Germany from 1933 to August 1939.

He also, though, took care to praise the internationalist section of the Republican Party whose votes he wanted and some of whom had senior positions in his Administration. Turning to his own time as President, Roosevelt intensified the attack on the trade and security politics of his political opponents:

We know that after this Administration took office, Secretary [of State, Cordell] Hull and I asked that high tariffs be replaced by a series of reciprocal trade agreements under a statute of the Congress. The Republicans in the Congress opposed those agreements – and tried to stop the extension of the law every three years. I am just talking about their votes [in Congress]. In 1937, I asked that aggressor nations be quarantined. For this, I was branded by isolationists in and out of public office as an ‘alarmist’ and a ‘war-monger’. From that time on, as you well know, I made clear by repeated messages to the Congress of the United States, and by repeated statements to the American people, the danger threatening from abroad – and the need of re-arming to meet it.

And it was made plain to Mr Hull and me that because of the isolationist vote in the Congress of the United States, we could not possibly hope to obtain the desired revision of the Neutrality Law. In 1941, this Administration proposed and the Congress passed, in spite of isolationist opposition, the Lend-Lease Law, the practical and dramatic notice to the world that we intended to help those nations resisting aggression.

The majority of the Republican members of the Congress voted – I am just giving you a few figures, not many – against the Selective Service Law [selective compulsory military service] in 1940; they voted against repeal of the Arms Embargo in 1939; they voted against the Lend-Lease Law in 1941; and they voted in August 1941 against extension of the Selective Service – which meant voting against keeping our Army together – four months before Pearl Harbor.4

Roosevelt’s argument was that the Republicans had prevented the development of global security organizations and free trade, alienated allies, built up Germany and tried to prevent all resistance to the dictators. His critics argued that Roosevelt needlessly provoked the Germans and Japanese and had responsibility for the failure of an international economic conference in 1932 supposed to revive international trade.

His argument about the difficulty of getting Republican support to stop Hitler becomes clearer when we look in more detail at America’s reaction to Hitler’s successes in 1939 and 1940. In March 1939, Hitler attacked that part of Czechoslovakia he had not been given at Munich six months before. Poland joined Hitler in carving up Czechoslovakia by seizing the area around Techen. In Spain, Franco finally defeated the democratic government. Then, in July, discussions between Britain, France and the Soviet Union on a military alliance against Hitler collapsed – the Western Europeans showed little interest in working with the communists. Stalin cut his losses and stunned the world by making an alliance with his ideological arch-enemy, Adolf Hitler: in August 1939 they announced their pact. A few weeks later, in early September, Hitler attacked Poland from the west. Stalin then moved into Poland from the east, overrunning the country. The British and French, having declared war on Germany, declined also to go to war with Russia, accepting the Soviet explanation that they were protecting people from the Nazis. People soon began to suffer under the Nazi and Soviet occupations, and by the summer of 1940, Stalin had moved to take over the Baltic States.

In response to these events, Roosevelt at last felt able to ask Congress to repeal America’s Neutrality Act, which banned sending help to states at war. After six weeks deliberation, Congress voted to allow Britain and France to buy US weapons for cash, but took away authority for them to be transported on US ships, something that had been legal, thereby giving help in one way while restricting it in another. This extraordinary restriction may have been designed to keep the US out of the war, but it was of direct help to Hitler, who no longer hard to worry that the weapons would be carried on American ships which he could not sink without going to war with the US. The Allies could now buy US weapons, but could they get them across the U-boat infested Atlantic?

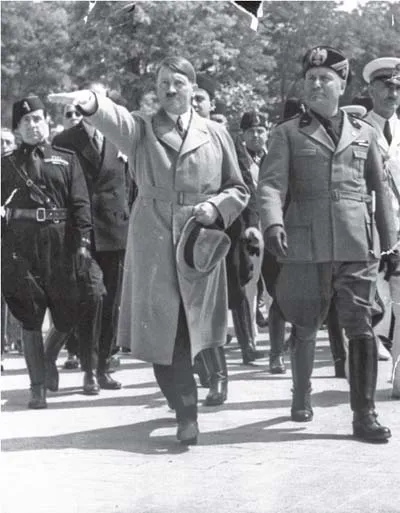

3 Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

Too little, but not quite too late, Congress began to pay for more weapons for US forces. In 1940, Americans were still spending less on the military as a proportion of national wealth than they had in 1932, in the depths of the recession. In 1938, Roosevelt had sought increased spending for the production of 20,000 warplanes, but had been rebuffed in Congress.5 Only in 1941 did spending increase substantially, including an order for a dozen aircraft carriers.

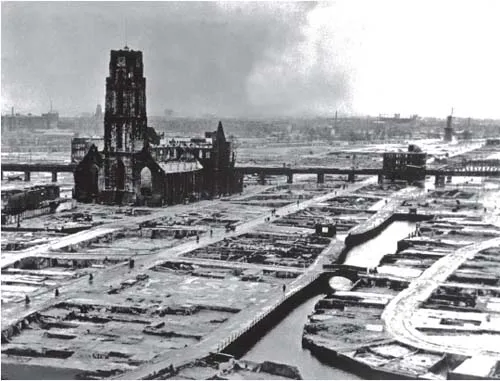

4 The Dutch city of Rotterdam after German bombing in May 1940.

Legislators failed to take advantage of one of Roosevelt’s most far-sighted and least-remembered preparations for war. In 1933, he requested the defence industry to offer a range of the latest high-tech weapons. Of these, one of the most famous was a bomber aircraft – the B-17 Flying Fortress – built by the Boeing aircraft corporation as early as 1935 to meet a War Department specification which resulted from Roosevelt’s 1933 request.

In the summer of 1940, however, the US had few modern weapons and few trained men – the army had just a few hundred thousand compared to millions in those of Germany, Britain, France and the Soviet Union. Only after Dunkirk, when it appeared Britain could fall to the Nazis, did Roosevelt think it possible to get a law past Congress compelling young men to register for compulsory selection for a year’s military service. At this point in the war, Hitler’s tanks and warplanes had destroyed the British and French armies in Europe and bombs were falling on London and other cities. Britain stood alone, expecting Hitler’s invasion fleet of air- and seaborne forces and braced to fight another battle at Hastings, where the English had lost 900 years earlier to the Norman conquest.

In America by 1940, there were two main political movements vying for the support of the American people in relation to the war in Europe. These were America First and the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies (CDAAA).6

America First was a broad alliance or a ragbag of misfits depending on one’s point of view. It contained pacifists, communists, those who favoured fascism and feared communist revolution at home and abroad, those who hated British Imperial domination from Ireland to India, and those who believed that America could get along fine protected by its navy and the wide Atlantic and Pacific oceans.7 The CDAAA leaders were William Allen White of the Kansas City Emporia Gazette and Clark M. Eichelberger of the League of Nations Association. The Committee to Defend America sought to link the need to help those fighting to the ideas that this was a fight for freedom against tyranny and that victory would be accompanied by a better world.

Both groups sought to influence the 1940 presidential election. Then, as now, the nomination and election campaigns were a long-drawn-out affair. When the Democrat and Republican Party conventions met in the summer, it was after Dunkirk. Gallup polls showed that American public opinion had swung towards fighting alongside Britain if this was essential to stopping Hitler from winning.

The Republicans were focused on attacking Roosevelt’s economic New Deal, including financial programmes to support the elderly and unemployed and nationalization of businesses. Front runners were the gang-busting New York state prosecutor Thomas Dewey and Senator Arthur Vandenburg. The convention in Philadelphia that July ended up choosing neither of them. Wendell Willkie, a charismatic lawyer and lobbyist for the electric power and other private utilities, came in as an outsider. One of his advantages was that he had no record of opposing involvement in the European war. At this time the Republicans needed a candidate untainted by isolationism but likewise not bent on war, and Willkie was the only contender to fit that specification. The Republican platform blamed Roosevelt for the failure to resist Hitler and gave a commitment to ‘all peoples fighting for liberty, or whose liberty is threatened, of such aid as shall not be in violation of international law or consistent with the requirements of our own national defense’.8

The vagueness was satisfactory to the competing factions in the party, but barely edged ...