![]()

| CHAPTER 1 Getting wise about water | |

This book will shock you into thinking about water in new ways. Put simply, we human beings don’t understand the true value of water, and we are at a point in our relationship with nature’s vast but limited water resources where we simply cannot afford to stay ignorant. Already, our over-consumption and mismanagement of water has had a very serious impact on our water environments and the essential services they provide.

Our ignorance is immense. Most of us don’t have the slightest idea about the sheer volumes of water involved in our daily lives. At the start of the twentieth century, with a global population of one billion, this ignorance simply did not matter. The ratio of water to people was so massive that it was as if our water supply was infinite. But it is not. And now, with a global population pushing seven billion, water scarcity is not just a possibility. It is already a reality for many.

Our imagination allows us to understand water scarcity in far-off places. We can picture the arid desert, the drought-cracked soil and treacherous dirty water supplies reported in news footage and charity appeals. Water scarcity belongs in the world of famine, cholera and five-hour treks to the nearest reliable well. In the industrialised world, where clean water is forever available at the simple turn of the tap or twist of a bottle top, we can’t conceive of the possibility of its absence. The hydrological and economic processes that make this possible are an invisible hand, operating outside the scope of our daily concerns. But this hand is faltering.

How much water do you have for breakfast?

We are addicted to over-consuming water, and we don’t know it

It’s an easy question: how much water do you have for breakfast? You might think you have none. Then you might remember that, of course, there is water in your tea or coffee. And your milk. Isn’t there, technically, some water in that? So, you’re having at least 300–400 millilitres. Right?

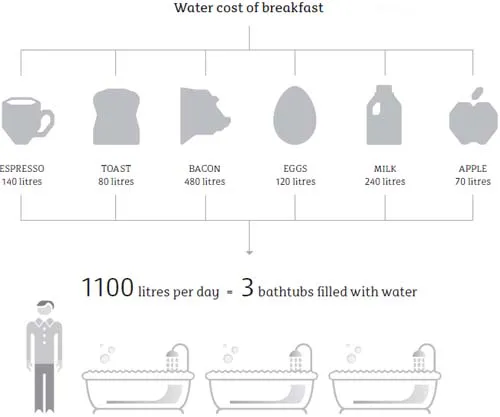

Let’s look a little closer. Take a normal – if slightly indulgent – breakfast in the US or UK. There is a cup of tea or coffee, a slice or two of toast, perhaps bacon and eggs, maybe a glass of milk, and possibly a little fruit as a nod to health and a leaner waistline. Now, what is that in water terms? Let’s start with coffee. Well, you might say, I like my coffee strong. There’s barely any water in there at all. Maybe...But what if I told you that in your tiny espresso there is 140 litres of water. Yes – 140 litres. You might think I was slightly deranged. But that is the virtual water hidden in the coffee. That is the amount of water used in growing, producing, packaging and shipping the beans that make the coffee. Here is a simple example of what we mean by something’s cost in virtual water. It is, I am sure you will agree, rather a lot more water than you first thought. But it is just the tip of your breakfast’s virtual-water iceberg.

There’s the toast. Forty litres of water are expended to bring that toast to your table. Per slice. That is the cost in water of making, transporting and finally toasting. An apple is 70 litres. The eggs are 120 litres. Throw in a glass of milk at 240 litres. And then there is the bacon, at 480 litres for one portion. In all, this full English breakfast has cost about 1100 litres. That’s a little over a cubic metre of water. If you find it hard to imagine a cubic metre of water, imagine a full bathtub. Now imagine three baths. Full. That is the cost of your breakfast in water.

Figure 1.1 The cost of breakfast in water, in the UK or US.

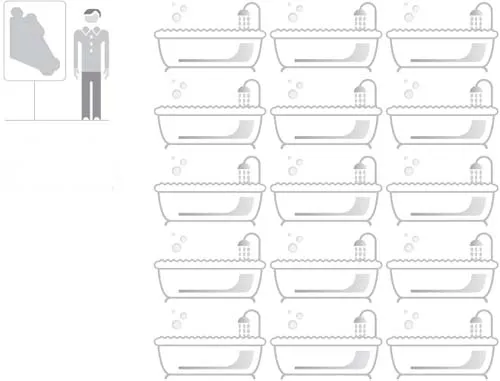

Of those three baths, over two-thirds of that water goes towards making the animal products – the milk, the eggs and the bacon. The meat non-vegetarians eat is the biggest single source of water consumption in their life. The average non-vegetarian diet in the US or Europe consumes about 5 cubic metres of water each day. That is 15 bathtubs, each and every day, consumed just to keep one person fed and watered.

Figure 1.2 Daily water consumption of a non-vegetarian diet: 5000 litres of water per day, namely 15 bathtubs filled with water.

Vegetarians can consider themselves a bit more frugal on water consumption; they only need eight bathtubs per day. Consider the millions of people living in the Western world, and consider all those bathtubs of water. It is a colossal figure.

Figure 1.3 Daily water consumption of a vegetarian diet: 2700 litres of water per day, namely 8 bathtubs filled with water.

That’s the industrialised nations, but what about the emerging BRICS economies? Let’s look at what is for breakfast in India, a fast-growing economy and the ‘I’ in BRICS. For the vegetarian, breakfast will be grains, vegetables and vegetable oil. In Southern India, you might wake up to idlis, vadas, dosas, salty pongal, rounded off with some hot sambar and at least one variety of chutney. In all, this only costs about 300 litres of water. In China, breakfasts are slightly more indulgent and more likely to contain meat, as well as bread, noodles and porridge. They average 600 litres. Brazilians love their meat for breakfast, and so their breakfast costs as much as, if not more than, the average Western breakfast in water terms.

The other 160 or so countries in the world range from the very wealthy Arab oil nations to the extremely poor states of sub-Saharan Africa. In the Middle East, discounting the oil-rich countries, meat is rarely the cornerstone of the diet, as it is in the industrialised world. There, the average person requires a half to two-thirds of the amount of water each day consumed by the average person in the US and Europe. Throughout this book, we’ll find that money and water (nearly) always flow in the same direction.

BRIC(S) AND WATER

Though well established in the discourses of economics, geopolitics and academia, the acronym BRICS may be unfamiliar to many. It stands for Brazil, Russia, India, China and sometimes South Africa. Occasionally, we see BRIICS, which is the same but with the addition of Indonesia. These economies are singled out as not fitting the model of either the industrialised nations of the Northern Hemisphere – plus Australia and New Zealand – or the less industrialised, developing nations of the South. We’ll be returning to them throughout this book. Their importance both to virtual water and the world in general cannot be overplayed. It’s no exaggeration, though an appalling piece of punning, to claim that BRICS are what will keep the global house standing in the future.

By now, you might be getting a sense of the amount of water you consume in the course of a year. If you are a meat-eater in the US or Europe reading this book, to get a rough sense of your water usage each year, imagine a house. A nice big three-storey house. With three spacious rooms on each floor. It’s 10 metres deep and 10 metres wide. It’s a large, generous-sized house, a family home. Fill it with water until every last room and corridor is bulging. Until the windows are rattling under the pressure and the whole thing looks as though it might suddenly explode. That is the amount of water you are using each year. Of course, you are drinking only a tiny fraction of that. A large wardrobe should slake the thirst of all but the most avid water-quaffer. Those other times when we are clearly, consciously and directly using water – the baths, showers, cooking, washing up, cleaning clothes, toilet visits – account for a little more, perhaps a roomful. All the non-food commodities we buy account for another roomful. And the rest, amazingly, is food. It can’t be reiterated enough: most of the water you use comes through your food consumption. Forget bricks in the toilet cistern: going vegetarian would save many lifetimes of toilet trips. Luckily, in the US and Europe, our jobs are pretty water-friendly. Service-sector salaries between $30,000 and $150,000 represent quite spectacular returns on only a couple of wardrobes of water. It is no coincidence that we in the developed world have managed to squeeze the greatest incomes from the smallest quantities of water. We might even put that forward as a definition of a wealthy industrialised nation: one that has maximised the financial returns per cubic litre.

Water is for life...not just for drinking

Water is one of the key components of life. Without it, we would be dead very very quickly indeed. All living things need water: it is the main building-block of the living cell. Water is also the basic ingredient of all bodily fluids: it flows in the vessels of our body and accounts for over 70 per cent of our bulk. Without it, we wouldn’t be able to move nutrients around our body. Internally, we would pretty swiftly become a dried-up riverbed, with fish, boats and discarded boots sitting motionless in the mud. As should be becoming clear, water is also vital to food production. Food is essentially the result of nature’s highly evolved integration of air, water and energy into vegetation. If we human beings are perched at the top of the food chain, then water is down at the bottom, making every last bite and gulp we take possible. If the bottom wobbles, the top falls.

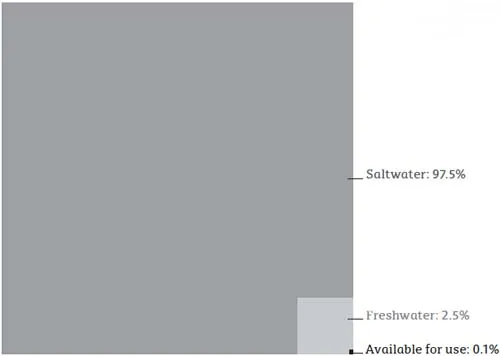

Mother Nature is – like all good mothers – a bit extravagant and overindulgent to us children. When it comes to water, we have a superabundance. Seventy per cent of the world’s surface is covered with the stuff. But most of it – 97.5 per cent – is salty and of very limited use to us. Of the remaining 2.5 per cent, only a small fraction is actually of sufficient quality to be used by the world’s plants and animals. So much for mother’s love, you might think.

Figure 1.4 Plenty of water but not as much as you might think.

Each year, about 110,000 cubic kilometres of rainfall drops on the earth: that is a one-metre-thick blanket of water wrapped around the entire planet each and every year. Of this global freshwater, just over half evaporates or is transpired by vegetation and crops. Another 36 per cent ends up in our streams, rivers and lakes, and ultimately in the oceans. We humans now only make use of 6.5 per cent of rainwater.

As we clear away natural vegetation and redesignate land for crop growth, so too are we diverting water from nature and introducing it into our human economy. Yet somehow, while economists have been happily integrating land and raw materials into their theoretical factors of production, water has fallen outside their calculations. In this book, we are going to discover why that has to change. Water is already an invisible, potent force in the global economy, perhaps an over-riding force. Although, as we shall see, locally, even its near-complete absence can be mitigated. Just as our land-centric attitude enables us to name a planet predominantly covered in water Earth, so too we manage to remain wilfully blind to the pivotal role of water in our world economy. How do we manage this collective perceptual fraud? What is the explanation?

The answer perhaps lies in the history of our relationship with water.

A brief history of water use

Water scarcity has not been a problem. Until very recently in our history, our tendency to die early and reproduce poorly has kept global population below the one billion threshold. There were fewer of us and, in our pre-industrial state, we were using far far less water, about 1000 cubic kilometres a year worldwide, a fraction of 1 per cent of the freshwater available.

It has taken us most of our evolutionary journey to learn how to exploit water. First, we needed to come down out of the trees, which we did around seven million years ago. It was another five million years before we resembled current humans. But it was only in the Neolithic period, around 11,000BCE, that we developed arable farming. So was born virtual water. Until then, we only directly saw the water we used because we were either drinking tiny amounts of it or washing with very small amounts. By 10,000 years ago we were unwittingly diverting it via cultivation and embedding it in our food.

Like many fundamental behavioural seismic shifts, this one’s significance with respect to water was not noticed at the time. Only with considerable historical distance can we see the importance of that change. It was another two millennia before we managed to domesticate animals. Until that time, we had to rely on two basic energy sources: fire and us. Now we had a slave race of animals: horses and cattle became our main energy force. They moved us and our goods around. They tilled our land. Those that didn’t serve us fed us. And then, only two hundred years ago, a movement by turns economic, social, political and technological, definitively revolutionised our energy supply. Very recently, in the middle of the twentieth century – in the space of a few decades – most of North America and Europe was freed from a reliance on animals to farm and produce food, or to help produce goods and services or move them around.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

What do Elton John, Bob Dylan, Marilyn Monroe and Virtual Water all have in common? They all needed a name-change to get noticed. I first began talking about ‘embedded’ water in 1988, but the concept seemed to have little or no impact. It was only a chance remark at an evening workshop in London in 1992 that led to the coining of the term ‘virtual water’. A rose by any other name would certainly not smell as sweet from my experience. Perhaps it was the fashionable resonance of the word virtual in the digital-obsessed 1990s, but the concept took off very rapidly. Curious, not least as ‘embedded’ seems a more accurate and informative moniker than the ambiguous and nebulous ‘virtual’. Yet the term stuck, and is now familiar to every water minister in the world. Goodbye Norma Jean...

Until this industrialising moment in our very recent history, for nearly seven million years we had not really learnt how to pollute. We were too few, too spread out, and aside from some low-level killing of flora and fauna we had yet to make our mark on the planet. From water’s perspective, it was as if we didn’t exist. The water system could absorb our levels of pollution and happily carry on, entirely unchanged. Amazingly, it has only been in the past couple of decades that people in the industrialised economies have listened to calls for stewardship of the water environment. There is a widening awareness that our industrial methods of exploiting our water environments come with serious costs that are not internalised in the prices we pay for water-intensive goods and services.

iPods, aeroplanes and water

We human beings are users. I don’t mean that pejoratively. It is our great skill, which has enabled us to gain dominance (mostly) over this planet and all the other species. We are capable of and comfortable using complex technology intuitively and without an understanding of how it works. It’s the same with our own brains and the rest of our physiology. We do not understand them. But we use them. We are natural users and exploiters. I cheerfully listen to digitised music on my ergonomic iPhone, leaning back in the electronically reclining seat while travelling ...