![]()

| 1 | Introduction to the Gulf |

The Gulf conjures images of fabulous wealth. A thousand years ago, the legend of Sinbad told of intrepid sailors making fortunes from treasures and trade in the Indian Ocean. A century ago, Gulf waters were famed for yielding splendid pearls that bedecked royalty and rich bourgeois. In the petroleum era, the Arabian shore’s drab ports underwent rapid transformation into cosmopolitan hubs renowned for sleek architecture. Each era’s affluence accrued to a handful of fortunate merchants and rulers while most men and women have had to toil for basic necessities, whether by fishing, pearling, trading, farming or pasturing herds of camels.

In the span of history, the amount of wealth flowing to the Gulf due to oil exports is exceptional. The attention paid to the region by powerful external forces is typical of the modern era. In the 1600s, Britain and the Netherlands challenged the Portuguese; in the 1800s, Britain, France, Germany and Russia jockeyed for spheres of influence. Early in the twenty-first century, the Gulf was the scene of an extraordinary concentration of military power due to global dependence on oil and political rifts that threatened its flow through the Strait of Hormuz. The United States now maintains a string of military bases along the Arabian shore from Kuwait to Oman. The military budgets of the Gulf Cooperation Council states are vast for countries with such small populations. Iran’s Islamic Republic possesses an array of ballistic missiles and its nuclear power programme may result in its joining the ranks of nuclear states. In the current situation, we can see the recurrence of a historical pattern whose elements include geostrategic rivalry, military confrontation and a pivotal economic role for outside powers. Before delving into the history of the Gulf, let us consider the natural resources for economic activity and the forms of social and political organization that constitute the foundations for the sheikhs, kings and sultans who have sought to harness the Gulf’s potential.

While the Gulf has witnessed a parade of empires, it has never spawned its own major power. In fact, throughout history no local force has ever unified the Gulf. The dispersion of power and the role of external forces present a challenge to the task of framing a historical survey because the standard narrative approach is to define eras according to the rise, development and fall of dynasties and nations. But here we have to deal with a different kind of history, not the story of kingdoms and empires, for the region typically lay at the edge of empires forming a frontier and a passageway between them. Therefore, while this history says a great deal about the succession of powers that struggled to dominate the Gulf, it is important also to pay attention to the durable rhythms of economy and society that persisted whether Persians, Arabs or Europeans had the upper hand in one era or another. Those rhythms owed much to limits imposed and possibilities offered by climate and natural resources.

A survey of geography illustrates the environmental constraints on economic production, social organization and political development. Meagre freshwater supplies and extreme aridity account for low population density, making it difficult to marshal economic and material resources for a powerful state. The ancient civilizations of the Middle East evolved along the banks of the Nile and the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers: South Asian civilization arose along the Indus River; Persian kingdoms and empires developed on the far side of the Zagros range whose spring run-off feeds fertile lands. Along the shores of the Gulf, human settlement was concentrated at the few locations with freshwater sources.

The northern end of the Gulf is the outlet for the Shatt al-Arab, the river formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates. The Shatt irrigates fertile gardens and carries goods from the Gulf upriver for distribution in the Mesopotamian valley and for transport across the desert to Mediterranean destinations, and sends goods downstream for shipment to Gulf ports and beyond. South of the Shatt on the Arabian side the land is barren until one reaches the fertile aquifer-fed oases of al-Hasa, scene of densest settlement on either coast. Four to five dozen artesian springs flow into irrigation canals and channels watering date groves and vegetable gardens.

Across a shallow bay from al-Hasa lies the Bahrain archipelago, blessed with abundant springs. Its largest island, in medieval times known as Awal, more recently as Bahrain, is about 30 miles long and ten miles wide at its broadest point. The two other primary islands are Muharraq and Sitra. The entire archipelago is located in the midst of pearl beds. The Qatar peninsula marks the southern end of this relatively wet (for Arabia) region before the coast bends northward through the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to the tip of the Omani peninsula, which straddles four zones: on the west, the northern stretch of the peninsula forms part of the Gulf shore; the eastern side faces the Indian Ocean; along the central spine of the peninsula and bending southeast runs the mountain range called Jabal Akhdar; to the south is the edge of Arabia’s most barren desert, the Empty Quarter. At the feet of Oman’s mountains a string of aquifers supply water to oasis settlements. The northernmost extremity of Oman, the Musandam peninsula overlooks the Strait of Hormuz, across which lies Iran. From Hormuz to the Gulf’s northern end is nearly 600 miles. The Strait itself is about thirty miles wide.

While the Arabian shore is a long stretch of flatlands from the Shatt al-Arab to the mountains that rise some miles south of Musandam, the Iranian side is a narrow coastal plain between 15 and 40 miles wide behind which rise the Zagros Mountains. This range impedes communication between the coast and the interior, funnelling trade through a handful of passes and shielding coastal towns from easy domination by interior powers. By contrast, the lack of any physical barrier between the coast and the interior on the Arabian side facilitated trade and political domination by nomadic tribes over the coastal peoples. The Iranian shore is dotted by ports that trade between the sea and the interior plateau. Bandar Abbas was developed by a seventeenth-century Persian shah to serve as a point of exchange with European traders. Half a millennium earlier, the port was known as Hormuz. It had the advantage of proximity to a relatively lush region watered by a small river. The name Hormuz later became attached to an island in the mouth of the strait. A short distance away is Qeshm Island, where the British established a naval headquarters in 1820 to suppress piracy, only to abandon it after a few years due to the intolerable heat. Further up the coast are a string of historic ports: Lingah, Kish/Qais Island, Bushehr and Siraf.

The interior region served by these ports is Fars, the historical centre of Persian culture and civilization. A few miles from the sea, the land rises sharply, creating three distinct climatic zones, each offering distinct resources and opportunities for varieties of production and exchange. The coastal plain is a narrow band of sandy, barren land on which little besides date palms can grow. Further inland foothills are cut by fertile valleys and meadows watered by small streams coursing from high peaks. Here decent soil and careful use of water made possible cultivation of orchards yielding a variety of fruits. Towering over the foothills the peaks of the Zagros range forms a forbidding obstacle to human traffic except through narrow passes leading to the Iranian plateau which taps mountain run-off diverted to a maze of underground channels leading water to fields, villages and towns.

Compared to the rugged Iranian and arid Arabian shores, the sea offers a variety of riches. Its warm waters teem with animal life: fish, crustaceans and the dugong, a large aquatic mammal belonging to the manatee family hunted for its meat. For centuries divers retrieved pearl-bearing molluscs in shallow waters. Since the seabed on the Arabian side is generally shallow, pearling has been most intensive there, especially on either side of the Qatar peninsula, north to Bahrain and south to the Musandam peninsula. Less extensive pearl beds lie off the coast of Kuwait and in the shallow waters around Kish and Kharg Islands near the Iranian shore. To obtain pearls, divers scour the seabed at depths of 15–20 yards wearing stone weights to keep them submerged until they tug a rope to signal the crew to pull them to the surface. Water temperature varies by season, and the optimal time for divers is the warm months from May to October. Providing and provisioning a boat required a capital outlay normally provided as an interest-bearing loan by rich merchants. The captain, crew and divers hoped to recover enough pearls to pay back the loan, but frequently fell short and consequently carried their debt forward to the next year. Divers might bequeath their debts to their children, creating a form of debt bondage from which it was difficult to ever escape.

Before modern times, the best opportunity for accumulating wealth was by controlling ports to tax the flow of goods. The Iranian shore has an edge over the Arabian side because the deepest parts of the Gulf, for the most part a shallow body of water, lie close by. That explains the concentration of a succession of major port towns until modern times on the Iranian shore. Along that shore, no single location has the advantage of a superior natural harbour. Therefore, several ports and islands serve roughly equally well as points of exchange. The upshot is that Gulf history is marked by the rise and fall of port towns, influenced by changing trade patterns and the fortunes of external powers.

As a matter of broad historical conception, the shifting fortunes of Gulf ports make most sense when the region is viewed as part of a larger economic system encompassing the Indian Ocean basin and two types of exchange networks. In local networks, small vessels hugging the coast carried goods between Arabia and the Indus River delta. In long-distance networks, large ships connected the main ports in the Gulf, India, East Africa, Southeast Asia and China. Traders from all parts of the basin exchanged raw materials and manufactures with each other’s ports, and each port also looked to its own hinterland for exchange. No single zone – be it India, China, Africa or the Gulf – had a natural advantage over another, and no port within a particular zone had a natural advantage over another; therefore trade patterns constantly recalibrated according to market conditions and prices. Parity in access to goods and the sea lanes meant that no single location could monopolize trade without resorting to force, an element that was not introduced until the advent of the Portuguese in the sixteenth century. In other words, the economy of the Gulf and Indian Ocean had no natural centre. It consisted of networks that adapted to economic fluctuations arising from political disturbances.

1. Fishermen and Dhow in Oman.

The suitability of different sites for ports combined with the scarcity of water for cultivation and consumption to produce one of the distinctive features of the Gulf’s peoples, namely their mobility. Maritime trade is in its nature a mobile mode of existence, bringing sailors and merchants from different regions into contact. Because ports had roughly equal access to inland trade routes, it was possible for upstarts to challenge dominant centres. In the early 1600s, Hormuz Island lost its paramount standing in trade because Portuguese governors tried to exact too heavy a tax from merchants, who chose to relocate. In the early 1900s, Dubai lured traders from the Persian port of Lingah with low tax rates and cheap real estate.

Mobility was also part of the fishing and pearling economy, the latter drawing divers from the settled population for the five-month season. For the region’s purely terrestrial residents, mobility is the byword for raising livestock. Arabia is the land of Bedouin, whose very survival required seasonal migration with their flocks in pursuit of pasture. A political by-product of the population’s penchant for migration was the difficulty of establishing and sustaining control over people and resources. If fishermen, pearlers, traders or nomads found a local strongman oppressive, they moved with their boats, goods and animals to a more amenable place.

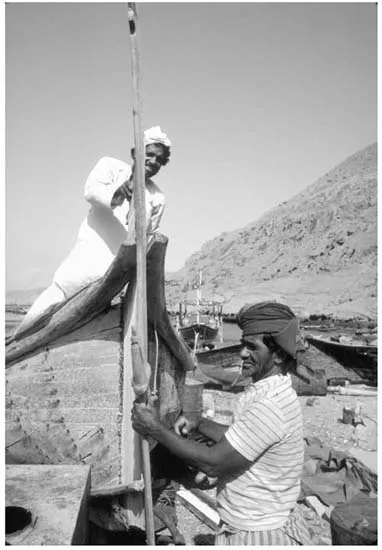

2. Making a Fish Trap in Bahrain.

The people of the Gulf inhabited three kinds of environment: coastal towns, oasis settlements and the desert. Coastal towns lived off the sea. Fishermen plied the waters in boats and cast nets from shore. Pearlers on the Arabian side dived for treasures during the warm months. Traders participated in exchange networks in the Gulf and the Indian Ocean world, benefitting from the regularity of the seasonal monsoon whose winds propel ships from Arabia to India during summer months and in the other direction during winter months. All three activities converged on shipbuilding, represented by the famous dhow. The margin of subsistence in all these fields of production and exchange was narrow. The surplus yielded by scattered populations was insufficient for the construction of large palaces or religious monuments. The thin bounty did not fund patronage for writers to produce literary testaments to a ruler’s grandeur. Therefore, the historical record is spotty, usually rendered by travellers passing through: Greeks, Arabs, Persians and Europeans. As a result, in speaking of how Gulf peoples organized their daily lives of production and exchange, we assume stability and continuity to fill gaps in written testimony that stretch for centuries.

Oasis settlements occurred where underground aquifers are close enough to the surface for cultivators to irrigate date palms. The date palm was more than a source of food for human nourishment. In an illustration of maximum utilization of the natural environment, Arabians used palm branches in the construction of homes and beds, fronds to make brooms, leaves to weave mats and baskets, and date kernels to feed animals. A variety of grains and vegetables was also grown in oases and supplied to traders and sailors residing in ports. The largest concentration of oases naturally occurred above the region’s most abundant aquifers: along the bases of the mountainous Oman peninsula and in al-Hasa.

On the Iranian side of the Gulf, cultivators confronted the same dearth of rain and surface water as their counterparts in Arabia. They excavated tunnels to channel snow melt from mountain slopes to the plains. This hydrological innovation called the qanat system minimized evaporation in a hot climate and enhanced storage capacity in a line of wells that tap the subterranean channels. The first qanats were excavated in Iran during the tenth to eighth centuries BCE. During the Achaemenid era (c. 550 BCE–330 BCE), Persian settlers introduced qanats to Oman, where the mountainous topography resembled that across the Strait of Hormuz. They made possible the spread of cultivation in the Omani interior and were the cause of the increase in population and number of towns, each based on a local qanat system. It is no exaggeration to say that qanats made it possible for Oman to develop strong states in different eras. Qanat irrigation supported a much larger population than would otherwise have been sustainable and that population supplied the manpower for a succession of Omani dynasties. Qanats were also excavated in Bahrain and al-Hasa during the Sasanian era (240–630) and helped account for their perennial prosperity.

The Bedouin of the desert raised livestock, primarily camels and goats, in a terrain that requires movement over a broad swathe of territory. Their migrations followed a seasonal rhythm according to the location of grazing sufficient to keep their hardy flocks alive. During long dry spells that could kill off a tribe’s animals, Bedouins would raid oases and coastal towns rather than starve. Even in flush years, settled populations normally paid tribute to powerful Bedouin tribes, the khuwwa or brotherhood payment, in reality a form of protection or extortion. The coercive dimension of Bedouin relations with sedentary folk was tempered by symbiotic relations. The Bedouin exchanged animal products for grain and riding equipment. They also served as guides and escorts for overland caravans, and supplied camels to bear loads of merchandise. In that capacity, they played a critical part in connecting the Gulf to centres of production and consumption in Syria and the Mediterranean lands.

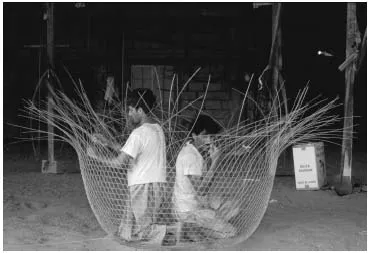

3. Bedouin Children in Saudi Arabia.

The dispersed, local scale of economic production and social organization, roughly equal up and down the length of the Gulf’s shores, obstructed the accumulation of power and its concentration in a single location able to dominate the region. In political terms, this meant two things. First, any single port, oasis or Bedouin tribe possessed a high degree of autonomy. Second, the dispersion of local power made the region vulnerable to domination by ambitious external powers. If we compare political patterns along northern and southern shores, we find variation due to their respective hinterlands. The northern shore forms a natural boundary for land-based kingdoms and empires with centres in the Iranian plateau. The first Middle Eastern empire, founded in the sixth century BCE by the Achaemenid dynasty near present-day Shiraz, inaugurated a history of Persian power in the Gulf, including periods of domination over much of the southern shore.

The Arabian side of the waters did not generate a comparable political force because the peninsula’s extreme aridity barred the development of economic foundations for empire. This is not to say that Arabia’s interior dynamics did not impact the Gulf. The most enduring legacy is, of course, the dominant religion, Islam, formed on the far western side of the peninsula in the seventh century. Apart from that singular event for world history, the movements of Arabian Bedouin tribes from time to time departed from customary migratory circuits to form waves crossing from south-west to north-east. In the early 1700s, such a wave of tribal movement brought to Arabian shores today’s ruling clans of Kuwait, Bahrain and Qatar.

Political history, then, is in large measure a record of the advent and recession of external powers (unless we view the northern shore as a natural part of the Persian realm; in that case, we would speak of the strengthening and weakening of central control over its southern periphery). During times of imperial assertion, the historical record is fuller due to the coins struck by royal mints and narratives penned by court chroniclers. At times of imperial weakness, the record is sk...