![]()

Chapter One

MATRIX OF POWER: THE ŚĀKTA PĪṬHAS AND THE SACRED LANDSCAPE OF TANTRA

Of all pīṭhas, the supreme pīṭha is Kāmarūpa. It bears great fruit, even if worship is done there only once … That pīṭha is the secret mouth of Brahman, which brings happiness, where Mahiṣamardinī [the goddess as slayer of the buffalo demon] dwells with her millions of śaktis. Since the gods, goddesses and sages are of this [Brahman] nature, they are all present here. Therefore, this place is kept secret by the great kula adepts.

—Kulacūḍāmaṇi Tantra (KCT 5.36–40)

—Judith Butler, Gender Trouble (1990)1

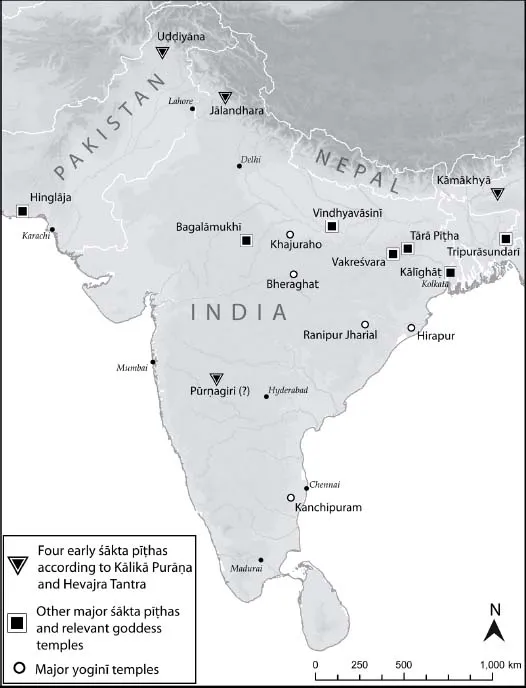

As a living, embodied, and historical tradition, Hindu Tantra spread throughout South Asia in a network of holy sites or epicenters of divine feminine energy known as the śākta pīṭhas or “seats of power.” Extending from Kāmākhyā in the northeast to Pūrṇagiri in the south and Uḍḍiyāna in the northwest, the śākta pīṭhas embody a complex, capillary network or matrix of power, comprising many veins and nodes that reflect the vast, flowing system of energy that is the goddess as śakti, embodied and embedded in the physical world. This matrix of power is from its origin born from bloodshed and sacrifice—the death and dismemberment of the goddess Satī, whose various body parts make up the śākta pīṭhas. But it is also intimately tied to the creative power of sexual union—the union of Śiva and Śakti who lie joined in secret love play on Kāmākhyā hill, giving life and vitality to the entire universe.2

In this chapter, I offer a brief overview of the history and context of South Asian Tantra, with particular focus on Kāmākhyā as one of the oldest and most enduring seats of power (Fig. 1). Today, it is impossible to say exactly when or where the complex body of traditions we now call “Tantra” originated. Various authors have suggested that Tantra’s origins lie outside of India (China, Tibet, the Middle East) or in non-Hindu indigenous groups (the hill tribes of northeast India) or in the mountains of northwest India (Uḍḍiyāna or the Kashmir Valley). There is no clear evidence of actual texts called tantras until the ninth century,3 though many believe their origins lie in Hindu Śākta or goddess-centered traditions going back to at least the fifth century.4

Yet virtually all the early sources agree that Kāmarūpa (the “form” or “body of desire”) is one of the oldest and most revered of the early seats of goddess worship and Tantric practice, dating back to at least the eighth century.5 The śākta pīṭhas in general and Kāmākhyā in particular, I will argue, represent a complex interaction or negotiation between mainstream Vedic or brāhmaṇic traditions and indigenous elements from the pre-Hindu areas of India. Particularly in the case of Assam, Tantra draws much of its power from the tremendous, dangerous, and potentially impure “power at the margins,” the power associated with non-Aryan traditions and with the dangerous forces at the edges of the Hindu social-political order.

The concept of śakti and the network of the śākta pīṭhas, I will suggest, also reveal both the usefulness and the limitations of contemporary models of power such as Foucault’s widely influential work. In many ways, the Foucaultian view of power as a shifting, capillary, and productive network of relations is quite helpful for understanding śakti as a pervasive, creative energy that flows through every aspect of the physical universe and the social order. Yet at the same time, as a “female power, engendering both life and death in its temporal unfolding,”6 śakti also reveals the inherent gender-blindness of the Foucaultian model; indeed, it forces us to grapple very directly with the gendered dynamics of power as it is played out in lived history, social relations, and political struggles. Finally, as we will see in the subsequent chapters, the Tantric view of śakti also highlights the fact that power is not simply an abstract theoretical concept but an inherently performative phenomenon. It is a kind of power that is continuously reenacted through the recitation of myth and the ongoing performance of ritual, sacrifice, festival, and pilgrimage.

Divine sacrifice and the origins of the śākta pīṭhas

The mythic narratives about the origins of the śākta pīṭhas tie together three key themes that later become central elements throughout South Asian Śākta and Tantric traditions: the themes of sacrifice, desire, and power. According to a well-known story found in various retellings in the Brāhmaṇas, the Epics, and the Purāṇas,7 Lord śiva was married to the goddess Satī, the daughter of Dakṣa. However, Dakṣa very much disliked his son-in-law, śiva, who is a fierce, frightening, outsider sort of god; so when Dakṣa arranged for a large sacrificial ritual, he intentionally did not invite śiva. This disinvitation was such a profound insult that Satī committed suicide by throwing herself onto the sacrificial fire. In his rage, Śiva became “Mahārudra, the god of destruction,” as “millions of ghosts and demons came out of his beauty and began a wild dance … The yajña was postponed and then became a wholesale massacre.”8 Having destroyed the entire sacrifice, śiva beheaded his father-in-law, Dakṣa, and replaced his head with that of a goat—the original sacrificial victim—thus making him the ironic victim at his own sacrifice.9

In sum, what we have in this myth is the story of a sacrifice gone awry, an interrupted ritual that turns into a dangerous, inverted sacrifice spun out of control. After destroying the sacrifice and beheading Dakṣa, the distraught śiva then carried off the body of his dead wife upon his shoulders. So terrible was śiva’s rage that it threatened to destroy the entire universe; so, in order to defuse the situation, the gods entered into Satī’s body and dismembered it. The various parts of Satī’s body then fell in various sacred places in India, the śākta pīṭhas or “seats of power,” which are intimately joined to Śiva in the form of his liṅgam. The oldest and most powerful of these seats are usually said to be Kāmarūpa in the northeast, Uḍḍiyāna in the north (probably in the Swat Valley of modern Pakistan), Pūrṇagiri in the south (real location undecided10), and Jālandhara (near Kangra, Himachal Pradesh). The Kālikā Purāṇa’s version of the story also adds two additional pīṭhas in Kāmarūpa and one in Devīkūṭa (in the Dinajpur district of Bengal):

The gods entered the corpse of Satī in order to tear it to pieces so that various [holy] places could arise on the earth where these pieces fell. First the feet fell to earth in Devīkūṭa. The thighs fell in Uḍḍiyāna for the good of the world. The yoni region fell in Kāmarūpa on Kāma hill. And to the east of that, the navel fell to the earth. The breasts, adorned with golden necklaces, fell in Jālandhara. The neck fell in Pūrṇagiri, and the head again fell in Kāmarūpa. Out of his love for Satī, bound in infatuation, Śiva himself remained in the form of a phallus wherever these pieces fell.11

The self-sacrifice of the goddess Satī and the creation of the śākta pīṭhas is thus an ironic inversion of a normal sacrifice. Indeed, it is a kind of twisted mirror of the original creative sacrifice described in the Vedas, the sacrifice of the Primordial Person (Puruṣa) recounted in the famous creation myth of the Ṛg Veda. In the Vedic narrative, Puruṣa is ritually dismembered by the gods in a primordial, creative sacrifice “in which everything is offered,” a sacrifice that generates all the various parts of the cosmos and the social order from the pieces of his severed body.12 In the Satī narrative, conversely, the sacrifice of the goddess is a destructive and nearly apocalyptic act—a sacrifice that threatens to destroy the entire universe because of its divine but dangerous power. And it infuses the earth, not with the abstract male principle of Puruṣa, but with the vital, creative but also destructive energy of the goddess.

As the seat of the goddess’ yoni or sexual organ, Kāmākhyā is widely regarded as the most powerful of the pīṭhas and, indeed, literally the “mother of all places of power.” According to the Kālikā Purāṇa, it is here that the goddess dwells in the form of a reddish stone, the physical embodiment of her yoni, which grants all desires; and it is here on the blue mountain (Nīlācala or Nīlakūṭa) that the goddess and lord Śiva lie in secret union, their yoni and liṅgam joined in lovers’ play beneath the mask of stone:

And in this most sacred pīṭha, which is known as the pīṭha of Kubjikā on mount Nīlakūṭa, the goddess is secretly joined with me [Śiva]. Satī’s sexual organ, which was severed and fell there, became a stone; and there Kāmākhyā is present.13

Kāmarūpa, the great pīṭha, is more secret than secret. There śaṅkara [śiva] always resides with Parvatī [the goddess].14

In sum, the Satī story combines the themes of sacrifice, dismemberment, and sensual desire, centering all of these powerful forces on the mountain on Kāmākhyā hill where the goddess and her lover lie in secret union. As Nihar Ranjan Mishra observes, “This narrative makes Nīlācala both a graveyard and a place of Śiva-Parvatī’s amorous pastime.”15 This fusion of the creative energy of desire and the destructive violence of sacrifice, we will see, lies at the core of Śākta Tantra and at the heart of the goddess’ power.

Later Hindu traditions would add a great variety of other śākta pīṭhas or centers of the Devī and her dismembered body parts, whose number varies in different lists, ranging from 3 to 108, though it is usually fixed at 51. Historically the oldest pīṭhas seem to be centered on two regions on the northern Himalayan range: Kāmarūpa in the northeast, which is mentioned in all the earliest lists of pīṭhas, and the Tantric centers of the northwest regions like Kashmir and the Swat valley. With the coming of Islam, the northwestern pīṭhas largely declined, and there appears to have been a proliferation of new pīṭhas emerging in northeast India, especially in Bengal.16 Today, the major living śākta pīṭhas include a wide array of vibrant goddess temples, such as Kāmākhyā in Assam, Kālīghāṭ in Kolkata, Hiṅglāja in Baluchistan, Bagalāmukhī in Datia, and Tārāpīṭha in Bengal. Together, the pīṭhas comprise a vast, interconnected, sacred landscape suffused with the goddess’ vital energy. As Sarah Caldwell observes in her study of Śākta Tantra in South India, “Throughout India, the earth is regarded as a sacred, living entity having a female nature. From the temple of Bhārat Māta in Banaras to Kāmarūpa in Assam … the land of India is infused with śakti, female creative power.”17

Sociologically, the pīṭḥas also played a key role in the culture of South Asia’s many traditions of siddhas (perfected beings), sādhus (holy men), yogis, and yoginīs. As Davidson notes, “Modern Indian sādhus congregate and encounter one another at sites of mythic importance, and it might be expected that such was formerly the case as well.”18 As we will see below, there is much evidence that Kāmākhyā was a central pilgrimage site for sādhus and siddhas from an early date, and today, one can find hundreds of holy men and women camped around the precincts of the temple. Along with Rishikesh, Haridwar, and Varanasi, it remains one of the most popular destinations for sādhus of every sectarian persuasion, but above all for the red-clad Śāktas who fill the temple grounds.

Finally, throughout Tantric literature, the geographic pīṭhas are also mapped onto the physical body and the sacred landscape of the individual self.19 As we will see in Chapter 4, the pīṭhas are typically identified with specific power centers within the individual human body, the microcosmic reflection of the divine cosmic body. And Kāmarūpa, the place of desire, is identified with the most hidden, most sacred place within the human body in which śiva and śakti unite in secret love: it is at once the yoni pīṭha or sexual organ of the female body and the secret center between the genitals and anus within the male body.20

The power of the goddess, in short, suffuses the macrocosm, the socio-cosm, and the microcosm alike, at once the geographic landscape of the śākta pīṭhas, the social landscape of South Asian religious life and physical landscape of the individual body. The enti...