![]()

1

Autobiography: The Externalisation of Personal Memory

Autobiography assumes a variety of forms and involves a range of practices. In literature alone, it encompasses ‘the memoir, the confession, the apology, the diary and the “journal intime”’, as well as less testimonial forms such as novels, drama and poetry.1 On another front, the revealing of personal histories has become a popularised practice through mass media such as tabloid newspapers or television – the chat show serving as an obvious example. Equally, autobiographical information has become a key part of the everyday administration or institutionalisation of our lives – in the filling out of insurance forms, applications for finance or social benefit, the recording of medical histories and so on.2 Operating on so many levels and in so many forms, autobiography plays a key role in Western culture and has come to represent a key issue of our time: the relationship of the private to the public. With this in mind, this chapter addresses the ways in which a number of artists have represented their histories and walked the often delicate path between the public and private spheres. I begin with a look at the prehistory of autobiographical art in self-portraiture, but for the main part this chapter is concerned with the work of artists who have made personal experience rather than the mirror-likeness of portraiture the lynchpin of their self-representations. What will become evident is that the current openness of expression in contemporary art has allowed for the terms in which autobiography is figured to be stretched and tested in new and significant ways.

The first artist to make self-portraiture a trademark of his work was, of course, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669). In a series of self-portraits that lasted his adult lifetime, Rembrandt brought a psychological depth to his self-imaging that went further than a simple chronicling of his changing appearance. Indeed, the amount of self-scrutiny that Rembrandt applied to himself in the seventeenth century was without precedent in the art of any culture and coincides with the emergence of the individualist self in the West. As literary historian Michael Mascuch has shown, this new tendency was expressed in part by the spread of new, more popular, practices such as personal almanacs and diaries. Until this point in history the model for autobiographical writing had been set by St Augustine in his Confessions and sat within a clear framework of religious and moral piety. By the seventeenth century, ‘the spiritual notebook was losing its status as instrument, and acquiring a new status as an object created by a subject; that is, an autonomous text, deliberately wrought by an individual intending it to represent some aspect of his personality’.3 This corresponds with the view expressed by Rembrandt’s contemporary Constantijn Huygens, that portraiture is ‘the wondrous compendium of the whole man – not only of man’s outward appearance but in my opinion, his mind as well’.4

The nature of Rembrandt’s gaze is crucial in relation to this access to the inner man. As art historian Gen Doy has pointed out, seventeenth-century portraitists were well aware of the way that the painted eye creates an illusion of captivating the gaze of the viewer wherever he/she may be positioned in relation to the painting, and even of following him/her around the room.5 But this alone is not enough to make the gaze compelling; in conjunction with this simple illusion, Rembrandt’s eye contact obtains because, while unflinching, there is something indefinable in it and it is almost constantly troubled. Again following Doy’s commentary on seventeenth-century portraiture in relation to notions of the self, it could be said that the nature of Rembrandt’s gaze bears the hallmarks of the sort of individual self-scrutiny that is associated with the philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) – the notion of a self-conscious, self-defining subject which, despite challenges from postmodern theorists, remains deeply embedded in the culture.6 Aligned with the compelling yet vulnerable nature of Rembrandt’s gaze, it is also a notion that privileges or encourages a romanticised interpretation of Rembrandt’s personality by those who read his self-portraits as autobiography.

However, the ‘story’ of Rembrandt’s life that emerges as the self-portraits follow on from one another is not an autobiography that looks back on the past to give it narrative shape. The majority of his images are not retrospective, and only a few serve to mark a life event such as his marriage to Saskia Uylenburgh in 1634. Instead, they are indicative of how Rembrandt wanted to present himself at a given time, in some cases to aid his pursuit of fortune and, in later life, to support his fame. The autobiography offered by the self-portraits has been constructed from without by critics and historians, who, as Gary Schwartz points out, insist on seeing Rembrandt as ‘a sensitive human being with great spiritual depths’ despite historical evidence to say that this was not typical of his conduct and character as experienced by his contemporaries.7 The self-images that Rembrandt offers seem, rather, to represent the selective nature of memory, both on the part of the artist, who presents a preferred view in order to memorialise himself, and on the part of the viewer, who, in the vein of Romanticism, wants to believe in the depths of humanity that Rembrandt shows us. In crude Freudian terms, Rembrandt may be said to present us with mementos of his ego-ideal (or, rather, a long series of ego-ideals) which act both as a conscience and as a counterpoint to the baser realities of his life.8 By extension, the ‘thinking’ self that Rembrandt portrays can serve as a kind of collective ego-ideal, and, as such, may be a key factor in his undeniable popularity.

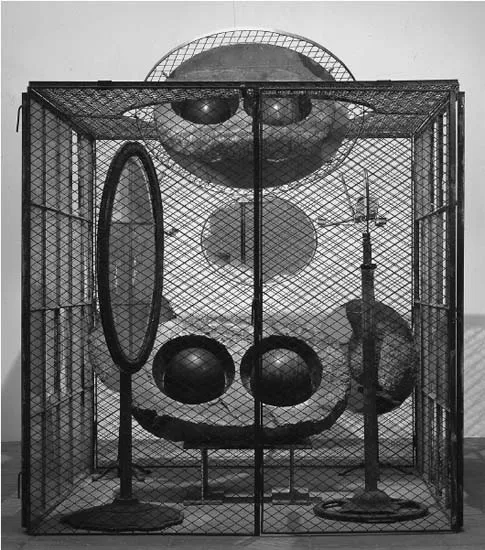

Figure 1: Louise Bourgeois, CELL (EYES AND MIRRORS) in progress 1989–1993. Marble, mirrors, steel and glass, 93 x 83 x 86 inches; 236.2 x 210.8 x 218.4 cm. Collection Tate Modern, London. Photograph: Peter Bellamy.

But the ego-ideal that Rembrandt presents is far from one of perfection, and the reason why Rembrandt’s self-portraits consistently find a widespread relevance is perhaps that they are not idealised, but touched by what art historian, Simon Schama, has called ‘the poetry of imperfection’. Even as Rembrandt seeks to impress with accessories and costume, his face is subject to ‘the pranks and indignities suffered by all mortal flesh’.9 In contrast to the human frailty expressed in his facial features, Rembrandt’s tendency to put on a show of material status in nearly all his self-portraits is also noted by Schama, and seen to be especially poignant in the self-portrait of 1658 held in the Frick Collection, New York. Here, despite being in the depths of misfortune, the artist presents himself not only with dignity but also in a rich costume that defies his circumstance (alongside a face that is, nevertheless, a continuing testimony to the vagaries of time and experience).10 Memory, of course, is inherently selective and there is a proven tendency to rework the original facts of an event or experience in a way that coheres around the wishes and values of the person remembering.11 So, while the actual truth value of Rembrandt’s self-portraits may be in doubt, what is important for his viewers are the human truths that they appear to embody.

In terms of memory or memorialisation, Rembrandt provides documents of himself that in chronicling physiognomic changes are literally autobiographical (the tracing of a life), but these traces, as already noted, are constructed in the present tense and most often bear a distant relationship to his actual circumstances and life events, and work more at the level of commemoration. This was echoed to some degree two hundred and fifty years or so later in the work of Rembrandt’s compatriot, Vincent Van Gogh (1853–1890). Yet, while Van Gogh’s recordings of his own likeness are also numerous and run a wide gamut of changing circumstances, they are more a poignantly truncated record in relation to a short lifespan and show a more rapidly changing self-image. In addition, while Rembrandt’s troubled gaze is often reiterated, Van Gogh’s self-portraits are more overtly diaristic than Rembrandt’s. His self-images reflect the actualities of his life far more directly and, in that respect, construct an autobiography based more closely on his life circumstances.

Van Gogh’s self-portraits shift from the conventional realism of the earlier self-images to an attempt to reinvent himself as a progressive and urbane artist when he arrives in Paris in 1886, as in Self-portrait with Light Felt Hat and Bow Tie, in which his dress is that of the fashionable townsman and his palette is lightened to match that of the avant-garde. But this is soon followed by self-portraits that document his changing mental state and re-identification with workers and peasants. This is strikingly shown in the portraits he made of himself showing his bandaged ear in January 1889, in the aftermath of his first major mental health crisis in Arles, and in the bleakness of his penultimate self-portrait painted in St Remy in September of the same year (Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo). In contrast to Rembrandt’s tendency to hide the particular circumstances of his life, Van Gogh’s often painful baring of both life and soul makes the private public and paves the way for the confessional practices associated with the autobiographical art of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. In this respect, his self-portraiture not only signals a paradigmatic shift in the genre of self-portraiture but expands the nature of the ‘memory-work’ that it performs.

Nevertheless, changeable as the self-portraits are in relation to Van Gogh’s health and circumstances, they almost all fit within the conventions of the mirrored likeness, usually head and shoulders, although sometimes with an arm and hand holding a palette. Exceptions to this format are found in two extraordinary self-images in which Van Gogh has substituted his face, firstly for that of Christ (Pièta, 1889, after Delacroix), and secondly for that of Lazarus (The Raising of Lazarus, 1890, after Rembrandt). In appropriating familiar compositions and religious iconography that are already ingrained in cultural memory, Van Gogh finds a vehicle for themes of death and resurrection pertinent to his situation both as an invalid and an artist. In this, he asks to be remembered as a victim and martyr to the larger forces and conditions that worked against him, both in his struggle to develop successful interpersonal relationships and in his struggle to become a successful artist in his own time.

A similar strategy is frequently replayed in the work of the last self-portraitist that I want to discuss, the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907–1954), who conflates autobiographical symbolism with cultural symbolism in a way that again sets particular terms for the ‘memory-work’ that her art involves. For the most part, Kahlo’s self-imaging divides into two dominant approaches: one which abides by the conventional format of the mirrored image (either head and shoulders or full-length), with personal attributes that often allude to the larger socio-political context that she inhabits; and one in which she illustrates or stages key moments in her life in a mise en scène of some sort. Representative of the first approach is a work such as The Two Fridas, 1939. In this large piece, Kahlo positions two seated full-length images of herself as if mirror images of each other – except that one wears what appears to be a colonial-style wedding dress while the other wears the traditional Tehuana costume of a south-west Mexican woman. A divided self is immediately suggested, but simultaneously denied by the entwining of the two figures with major blood vessels that grow from the exposed heart of each Frida. Painted at the time of her (temporary) divorce from leading Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, the ‘colonial Frida’ is the Frida that Rivera espoused while her ‘twin’ represents the Frida that Rivera had in fact encouraged and helped mould – the representative of an independent postcolonial Mexico.12 Significantly, the heart of the ‘colonial Frida’ is broken and sprouts an artery that divides, ending on one side in a severed state, staining the wedding dress, and on the other the heart of the ‘Tehuana Frida’, which is whole and which sprouts a further independent artery leading to a miniature portrait of Rivera’s head.

As others have observed, the personal can be seen to blend with the political in much of Kahlo’s work. In this case, the micro-politics of her relationship with Rivera are mapped onto the macro-politics of postcolonial identity, the tenuously linked hearts symbolising the pulls and stresses that the duality of identity exerted on Kahlo, born of a German father and Mexican mother and divorced from a man who she felt had refused to love her European side. While the bleeding heart can be seen as a symbol of Kahlo’s personal anguish, it is also central to both the iconography of Christ’s martyrdom and that of Aztec ritual sacrifice, functioning equally in both traditions as an emblem of suffering and surrender.13 In the almost diagrammatic fusion of the personal with larger cultural meanings, the separations and entanglements inscribed in the painting allude to rather than replay or restage the events or circumstances of Kahlo’s life. While the iconography is deeply encoded, the stylised technique and symmetrical composition also play a large part in the way that Kahlo chose to memorialise the dualities and inner conflicts of her identity.

In contrast, the self-images that depart from traditional portrait formats are different not only in the introduction of narrative but also because they introduce an element of retrospection and historicisation. However, works such as The Henry Ford Hospital (1932) and My Birth (1932) are more than simple recordings of past events; they are also, both literally and metaphorically, a reframing of these events. As art historian Gannit Ankori notes, The Henry Ford Hospital not only replays the trauma of miscarriage but overtly addresses a much broader trauma of identity. Kahlo herself referred to the piece as an ‘anti-nativity’ and represented herself as La Llorona, the weeping woman from Mexican folklore, who in various versions stands for evil, extreme violence, bad motherhood and sexual deviance.14 Similarly, My Birth draws a complex relationship between personal and collective history and mythology, compounded by an atemporal combination of Kahlo’s own birth and the death of her premature foetus in a single image, in which she is ‘born but gives birth to herself’.15 Thus, while more historically specific than The Two Fridas, My Birth and The Henry Ford Hospital also make similarly broad cultural references, connecting the personal to culturally shared mythologies and histories. This interweaving of personal memory with religion and myth not only allows for hindsight but also generates insight into the interweaving of personal memory within larger cultural schemes.

As Ankori suggests, the painting can be seen as an image of rebirth, a response to recent events that must have caused Kahlo to dwell on the idea and experiences of motherhood (a failed abortion, the adjustment to oncoming motherhood and a quickly ensuing readjustment to the miscarriage and the death of her own mother). On the other hand, Kahlo rejects any conventional image of mother and child, exposing the carnal reality of the female body, allowing Kahlo to rethink her identity as a woman.16 However, despite this flouting of iconographic convention, the work takes a conventional form – that of a domestic retablo, a votive image that is used to give thanks for escape from disaster, usually accompanied by an inscription.17 In this case, however, the inscription is conspicuously missing from the scroll at the bottom of the painting – a telling absence, given Kahlo’s habit of inscribing the scrolls in her more conventional self-portraits. The reason for the absence of the inscription becomes obvious when it is remembered that the painting refers back to the miscarriage depicted in The Henry Ford Hospital, in which personal disaster had been neither avoided nor overcome. Moreover, the missing inscription can also be read as a sign of...