![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Early Years

Dante Alighieri believed that he was a direct descendant of the ancient Romans. According to family tradition, a great-great-grandfather on his father’s side could trace his origins to the Elisei, one of the Roman families reputed to have founded Florence. This illustrious ancestor, Cacciaguida, was born towards the end of the eleventh century. A Florentine, he served, as other Tuscans did, in the Second Crusade, was knighted and killed in battle. His wife, Alighiera Alighieri, came from the region of the Po Valley, possibly Ferrara, and some of her descendants adopted her family name. Derived from the Latin word aliger, it means ‘winged’. Dante owed his Christian name to his mother’s side. A shortened form of Durante, it means ‘enduring’. The notion of ancient lineage, whether Roman or not, and names charged with such significance must have inspired in him a strong sense of destiny.

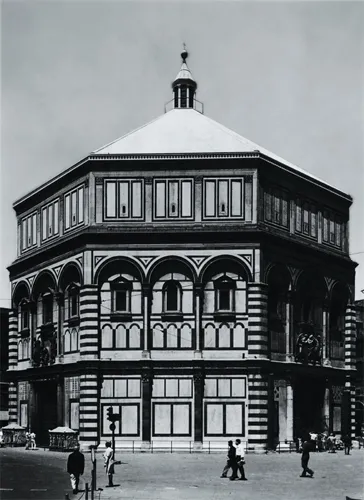

He was born in the year 1265. The precise day is not known but since he claimed the constellation of Gemini as his natal stars1 it must have been between May and June. He was christened the following year in the Baptistery of San Giovanni, one of the earliest buildings in Florence, where he believed that his ancestor Cacciaguida too had been baptized.2 The Cathedral, as we know it today, had not then been built and the Baptistery was more prominent than it is now.3 Dante called it his ‘beautiful San Giovanni’ and looked back to it from exile with longing, hoping one day to receive the poet’s crown of laurel there.4

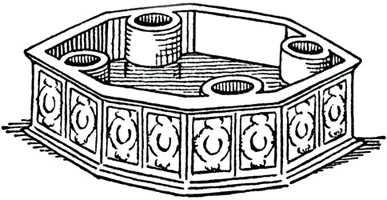

The original baptismal font is no longer in place, though broken segments of it are said to be in the Museum of the Works of the Cathedral. It was a low octagonal structure, like the font in the Baptistery at Pisa,5 and inside it, as at Pisa, were stone cylinders. Multiple baptisms were held twice a year, on Easter Eve and on the Eve of Whit Sunday, when the Baptistery was crowded with families and godparents. It has been said that the baptizing priests stood in the cylinders and leant forward to the water in the font. It is more likely that the priests stood in the dry font, facing the congregation and baptizing with water contained in the cylinders. One day someone (it has been said a child) fell into a cylinder and was unable to extricate himself. Dante smashed it with an axe to release him, an action that was considered sacrilegious. He makes a point of justifying himself in Inferno, where holes in the rock containing Popes guilty of simony remind him of these cylinders, one of which he broke, he says, to save someone who was drowning:

... e questo sia suggel ch’ogn’ uomo sganni.

... and by this seal let all be undeceived.6

His father, Alighiero Alighieri, was about 45 years old when Dante was born. A man of property, both inside Florence and in the countryside beyond, he added to his income by lending money, an activity which Dante later condemned as usury. By means of it, however, the father maintained his family in comfort and left them modestly provided for. Dante’s mother, named Bella, was the daughter of Durante Scolaro, said to be related to a distinguished family, the Abati. She died when Dante was a child, some time between 1270 and 1275, and his father married again. His second wife was Lapa, the daughter of Chiarissimo Cialuffi. She bore him two children: a son, Francesco, and a daughter, Gaetana. Another daughter (possibly of his first wife), whose name is unknown, married Leone Poggi. Their son, Andrea, was said by Giovanni Boccaccio, Dante’s first biographer, to look marvellously like the poet.

Boccaccio was eight years old when Dante died in 1321 and had never set eyes on him. Nevertheless, in preparation for his biography, he questioned many people who had known him, including his nephew Andrea. He describes Dante’s appearance as follows:

This our poet, then, was of middle height; and when he had reached maturity he went somewhat bowed, his gait grave and gentle, and ever clad in most seemly apparel, in such garb as befitted his mature years. His face was long, his nose aquiline, and his eyes large rather than small; his jaws big, and the under lip protruding beyond the upper. His complexion was dark, his hair and beard thick, black and curling, and his expression was always melancholy and thoughtful.7

From measurements taken of Dante’s skeleton in 1921,8 his height was between 1.644 and 1.654 metres, roughly the equivalent of five feet five inches. Measurements of the upper part of the skull confirm that his face was long. The nasal cavity suggests that the nose slanted slightly to the right and that it was large and aquiline. The orbits of the eyes show that they were large; also that the right eye was larger and slightly lower than the left. The cheek bones were prominent. The lower jaw is missing so its size cannot be verified. Calculations of the skull indicate that his cranial capacity was 1,700 cubic centimetres. The weight of his brain has been estimated as a possible 1,470 grams. These measurements suggest that his brain was above average in size and weight.9

In his youth he was not bearded, as can be seen from the portrait of him, said to have been painted by his friend Giotto, on the wall of the Bargello in Florence. This was damaged and badly restored in 1841 but some idea of what it was like originally can be seen from a sketch which the artist Seymour Kirkup was able to make of it before the damage had gone too far.10 This shows a sensitive, oval face, beardless, with a straight nose and firm chin. The prominence of the under lip, to which Boccaccio refers, can be seen in potential and this perhaps developed as he grew older.

There is no evidence that Dante felt himself an outsider among his father’s second family. An allusion in one of his poems to a sister standing at his bedside while he lay ill indicates, on the contrary, an affectionate relationship:

Donna pietosa e di novella etate,

adorna assai di gentilezze umane,

ch’era là ’v’io chiamava spesso Morte,

veggendo li occhi miei pien di pietate,

e ascoltando le parole vane,

si mosse con paura a pianger forte.

A lady, youthful and compassionate,

much graced with qualities of gentleness,

who where I called on Death was standing near,

beholding in my eyes my grievous state,

hearing babbled words of emptiness,

began to weep aloud in sudden fear.

These lines are the beginning of a canzone which Dante included in a selection of his early poems, entitled La Vita Nuova.11 In a prose commentary he explains that this ‘kind and gracious young woman’ was closely related to him. The traditional interpretation is that she was his half-sister, Gaetana, who in the year of Dante’s illness, 1290, would have been about 15. Apart from this brief and tender reference, Dante does not mention his siblings, though it is said that his half-brother Francesco visited him in his exile and negotiated a loan for him. He refers to his parents once only, in Il Convivio, a work he wrote in the early years of his exile. Explaining why he is writing in the vernacular instead of in Latin, he gives as one reason his intimate love of his native speech, which he feels is part of his very being. This is literally true, he says, because his parents spoke it and this brought them together and so was responsible for his existence:

Questo mio volgare fu congiugnitore de li miei generanti, che con esso parlavano ... per che manifesto è lui essere concorso a la mia generazione, e così essere alcuna cagione del mio essere.

This vernacular of mine brought my parents together, for they spoke in it ... so it is obvious that it had a share in begetting me and thus is a cause of my existence.12

In these words we can sense Dante’s longing to hear the Florentine speech again. It may even be that he is here recalling an echo of his mother’s voice: con esso parlavano: he seems to be remembering his parents talking together. If so, this must be one of his earliest childhood memories.13

His father died some time between 1281 and 1283, leaving Dante, then in his late teens, under the authority of a guardian, as the law required, until he was 25 years of age.14 From the many images of parenthood that occur in the Commedia it would seem that the early loss of his mother and later of his father left Dante with an emotional need. Several times he writes of himself as a child: held in the protective arms of Virgil, carried sleeping up part of Mount Purgatory by St Lucy, turning to Beatrice like a little boy to its mother for reassurance in a moment of panic; once he even compares himself to an infant hungrily mouthing for the breast.

After the death of his mother, his most important childhood experience was his meeting with a little girl of eight when he himself was nearly nine. Describing this event later in La Vita Nuova, when the child, grown to womanhood, had married and had died, Dante, by then an established poet, idealized the feelings she aroused in him at this first meeting as the beginning of a life-long submission to the power of love. In a realistic sense, it may have been his first awareness of the stirrings of puberty. Later in life, in a sonnet addressed to a poet friend, Cino da Pistoia, he admits that the origins of his feelings for her were sexual.15 In another poem he even traced her influence upon him to the day of her birth, when, he says, his little childish body felt a strange tremor and he fell to the ground.16 Since he was then only about nine months old, he could not have remembered this. If there is any truth in it, he may have suffered an infantile convulsion about which his nurse or his mother told him later. He describes himself as having a tendency to faint when overcome by strong emotions, as when in La ...