![]()

1

DRY FUTURE: JUST IMAGINE (1930)

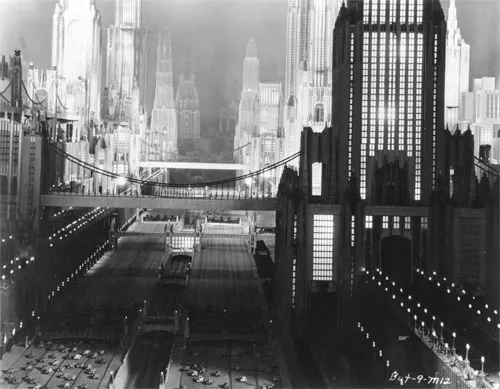

The city shone. Gleaming white towers formed broad avenues laid out with ribbons of garden. Bridges arched gracefully between the ranks of buildings, carrying trains and speeding lines of automobiles; some streets plunged into tunnels through the larger towers. Between the skyscrapers neat formations of aircraft crisscross the city. We notice two single-seat monoplanes in particular. They pull to a standstill and hover next to each other using propellers mounted horizontally in the wing. The young male pilot of one jumps onto his wing and hops nimbly across onto the wing of the other. A young woman smiles up from the controls and the action begins ...

It was a scene unlike anything in American motion pictures to that point. A vision of a possible future realized with a level of detail had been seen only once previously, in Fritz Lang’s lavish German masterpiece Metropolis (1927). This was the first sight of the future New York in Fox Metrotone’s Just Imagine, the film with the distinction of being Hollywood’s first major SF film. Here for the first time were many elements that would become commonplace in the decades to come, the most obvious being contemporary comment. Just Imagine was a genre piece before the cinematic genre had fully formed: a paradox that led to a flurry of allegations of plagiarism from writers who considered themselves to be the only possible originators of its ideas. Other films would seek to impress the audience with lavish spectacles of the future and space travel, and beguile them with speculation in risqué fashions in the future, but Just Imagine would remain unique in one regard: it would be the only SF musical.

The origins of Just Imagine lie not in America’s traditions of experimental fiction or genuine social or scientific speculation, but on that familiar epicentre of American fantasy: Broadway. Just Imagine plundered the emerging aesthetics of the imagined future to serve the ends of musical entertainment and make a political point – satirizing Prohibition – along the way. It was the creation of Fox Metrotone studios and the highly successful team of lyricists Buddy DeSylva and Lew Brown and composer Ray Henderson.1 Individually, each of the three had already made a mark with songs that became part of the American landscape. The team first came together on Broadway in 1925. Their collective output included standards like ‘Button up your Overcoat’, songs showcasing African-American entertainers including ‘Black Bottom’, and songs for ‘Minstrel’ entertainers like Al Jolson for whom they wrote ‘Sonny Boy’. In October 1929 they scored a massive hit with the film musical Sunny Side Up for Fox. It was a cheerful ‘cross town’ romance set in New York City. Tunes included the highly hum-able title song ‘Keep your Sunny Side Up’. The director of Sunny Side Up, David Butler, attracted attention with mobile camera work and experimental colour sequences. The film’s real success lay in its being available at the very moment that the bottom dropped out of the American economy. It became America’s escape from the Wall Street Crash. The film did well enough to guarantee studio demand for a swift follow-up. The follow-up would become Just Imagine.

In seeking to repeat the success of Sunny Side Up, DeSylva, Brown and Henderson sought an amalgam of the previous film’s successful elements: music, romance and comedy. The new future setting added a dose of escapist fantasy. It was a promising strategy to show a comfortable future in the midst of a distressed present. Studio documents reveal that Just Imagine was a pet project of DeSylva particularly. He had long since noticed the potential for a musical set in the future – some of the ideas seen in Just Imagine were road-tested on stage in The George White Scandals of 1926. In fact he recalled raising the idea of a ‘futuristic musical comedy’ when he first began contract negotiations with Fox studio executive Sol Wurtzel, long before Sunny Side Up.2

The core plot of Just Imagine concerned a standard pair of lovers divided, but that still left the need for comic relief. In Sunny Side Up the humour had been provided by one of the most popular screen comedians of the era, El Brendel, who played the poor girl’s downstairs neighbour Eric Swenson. The new film would place his talents front and centre. Brendel was a dialect comedian whose screen persona was a hapless thickly-accented Swede with a propensity for phrases like ‘yumping yiminy’. Born in Philadelphia from a German/Irish family, Brendel had begun a career in vaudeville in 1913 with a German dialect routine. With the wave of anti-German feeling that surged across America during the Great War, Brendel judiciously evolved his Swedish persona and prospered, performing with his wife Flo Bert. The humour was gentle and played on the anxieties of an immigrant nation whose citizens found understandable release in laughing at someone less adjusted to life in the new world than themselves.3 The same dynamic was seen at work in the ‘greenhorn’ tradition in Jewish comedy.4 By 1921 Brendel was a regular on Broadway. His success was such that even before the coming of sound he had a contract in Hollywood, joining Famous Players in 1926. He signed with Fox in 1929. In the wake of The Jazz Singer Brendel was ideally placed to exploit the new technology with its demand for amusing audio to match the pictures. His speaking roles included the rookie flyer turned mechanic Herman Schwimpf in Wings (1927) and in 1930, the comic role of Gus the Swede in The Big Trail (1930).5 In Just Imagine Brendel played an Everyman from the present revived fifty years in the future – a take on the familiar idea of the sleeper waking in the future familiar from Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel of 1888 Looking Backward or William Morris’s British response News From Nowhere (1890), or H. G. Wells’s When the Sleeper Wakes of 1899. There was no particular plot reason for making him a Swede, though the characterization made a certain sense if one imagined a modern man fifty years adrift in time as the ultimate greenhorn immigrant.

The most exciting element of Just Imagine would be its future city settings. These were the work of the set designer and art director, a former architect named Stephen Goosson. As James Sanders has noted, Goosson drew inspiration from the work of the late Italian futurist Antonio Sant’ Elia, the New York architect Harvey Wiley Corbett and most especially the drawings that Corbett commissioned from Hugh Ferriss, which reached a wider public as a result of his book of illustrations, Metropolis of Tomorrow, which appeared in 1929.6 These influences had already shaped Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. With an unprecedented budget and a dirigible hanger in Arcadia, California to work in, Goosson, together with the mechanical effects director Ralph Hammeras and their team, began the process of creating the city of the future. The fan magazine Photoplay reported:

It took 205 engineers and craftsmen five months to build it, at a cost of $168,000 ... . It was designed after long conferences with noted artists and scientists who dare to peer far into the future. Seventy-four 5,000,000 candle power sun arcs light the set from above. Fifteen thousand electric light bulbs illuminate its buildings and streets.7

The production was complex. The scenes set on Mars required casting multiple sets of identical twins. The film needed elaborate costumes, sets, miniature work and the brand new process of back projection, which worried studio managers. A studio lawyer wrote anxiously to Wurtzel:

It is my understanding that plans are being made for some trick photography in the new Butler production. If this is the case, I think that we should be sure what method is going to be used and whether or not we are laying ourselves open to any claim for damages by reason of existing patents.8

The production was apparently fairly uneventful. When interviewed in his later years the director’s only major recollection concerned the leading man John Garrick being stranded above the set in his mock-up aircraft during an earthquake.9

Just Imagine began with a preface in invoking the world of fifty years previously – 1880 – it depicted a sleepy street corner in horse-drawn New York City and then flashed forward to the same corner in 1930 following a hapless jaywalker and his attempt to cross the street without being hit by a car. With the distance to the past established, a narrator invited the audience to ‘Just Imagine’ the world of fifty years into the future: ‘If the last fifty years made such a change, just imagine the New York of 1980 ... when everyone has a number instead of a name and the government tells you whom you should marry. Just Imagine ... 1980!’ The scene shifts to the skies above the future New York where two lovers hovering in adjacent aircraft steal a conversation. The young man, an airline pilot named J-21 (John Garrick), has bad news for the woman LN-18 (Maureen O’Sullivan); the state marriage tribunal has ruled against his petition to marry her and instead favoured her father’s choice, an obnoxious newspaper proprietor named MT-3 (Kenneth Thompson), on the grounds that MT-3 has achieved more in his life. J-21’s appeal date is set for four months’ time.

Later, at home, J-21 confides his despair to his friend RT-42 (Frank Albertson). As a distraction, RT-42 and his girlfriend D-6 (Marjorie White) take J-21 to witness a medical experiment at D-6’s place of work: the revival of man who has been dead since he was struck by lightning on a golf course in 1930. At the lab they find an astonishing array of technology and ranks of impassive scientists. A mysterious ray revives the corpse (El Brendel) but the scientists have no further plans for the man and even offer to kill him again. Concerned, J-21 volunteers to help him find his feet in the new world. Noting that he predates the alpha-numeric naming schema of the day, they resolve to call him ‘Single O’.

Single O is disoriented by the sights of 1980, though fascinated by the revealing women’s fashions. When he realizes that food has been replaced by one kind of pill and illicit cocktails by another, he mourns ‘give me the good old days’. He makes the same remark when he sees a couple obtain a baby from a vending machine rather than through the traditional method.10 He cheers himself up by getting drunk on pills.

MT-3 forces LN-18 to reject J-21 and he wanders the city alone. A mysterious stranger finds him and offers to give the flyer his heart’s desire. J-21 is taken to meet a great inventor named Z4 (Hobart Bosworth), who reveals that he is looking for someone to pilot his rocket plane to Mars. J-21 recognizes his opportunity to distinguish himself beyond MT-3 and thereby get the court to rule in his favour. RT-42 agrees to join him as his co-pilot and the flyers celebrate their departure with an illicit drinking party on the airship Pegasus. They go to the launch site. As their rocket blasts away from earth Single O emerges as stowaway, under the impression that he was going to J-21’s ‘Ma’s’ rather than the planet Mars.

Landing on Mars a month later, the three friends encounter exotically costumed Martians, many of whom appear to be dancing girls. They are welcomed by the Martian queen, Loo Loo (Joyzelle Joyner). Single O is befriended by a large, camp, Martian male named Boko (Ivan Linow). The Earthmen are entertained to a bath and a show by performing Martian monkeys. As the show reaches its climax, they are attacked and captured by a second group of Martians led by Boo Boo (also Joyzelle Joyner) and Loko (also Ivan Linow), who are the physical doubles of the first. J-21 realizes that...