![]()

Chapter 1

Jedda Calling

Oil Negotiations, 1933

In those days, from the balcony of the Grand Hotel in Jedda, you could see the white minarets across the rooftops, hear the muezzin calling the faithful to prayer, and briefly imagine a romantic picture of Araby. As with other towns in Arabia, the modern age had bypassed Jedda, leaving it firmly entrenched in an earlier time. The narrow alleyways below the balcony were dark and winding, protected from the burning sun by mats and loose boards, while merchants did business from little booths in the suq. Street cries filled the air and camels passed by, loaded with freight or pilgrims on their way to the holy places.1

Jedda on the Red Sea was the main port on the western coast of Saudi Arabia and the gateway to Mecca and the holy places. In reality, Westerners found its climate unhealthy, the rain and cold of winter replaced by a rising humidity in the spring that presaged the unbearable heat of summer. In 1933 there were no modern amenities to speak of: the recently refurbished Grand Hotel had no running water, no air conditioning and toilets of sand. All the foreign delegations to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia were housed in the town. The British were the most numerous, followed by the Dutch, who spent most of their time looking after the large number of pilgrims arriving from the Dutch East Indies. The isolation of foreigners, however pressing or welcome their business, was a constant feature of life in the town and much felt by the diplomatic and consular corps.2

When T.E. Lawrence visited Jedda during the Great War, he felt the heat of Arabia that came out ‘like a drawn sword and struck us speechless’. In the alley of the food market, along the meat and fruit stalls, ‘squadrons of flies like particles of dust danced up and down the sun shafts’. The atmosphere, he concluded, ‘was like a bath’.3 Sir Andrew Ryan, British minister in Jedda between 1930 and 1936, described a tumbledown and squalid town that, although picturesque with an air of greatness, looked as though it had never quite recovered from the bombardment it had received from a British warship in the nineteenth century.4

There was little Western interest in the Arabian interior, apart from a starry-eyed attachment to the great sand desert, the Rub al-Khali which Bertram Thomas had crossed two years before. But an oil strike on the island of Bahrain in May 1932 had triggered the interest of an American company, Standard Oil of California (Socal), in the oil prospects of the Arabian mainland. Not to be outdone, their rival in the region, the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), was also attracted. Now the oilmen gathered in Jedda to discuss with representatives of the kingdom an oil concession for the eastern province of Al-Hasa.5

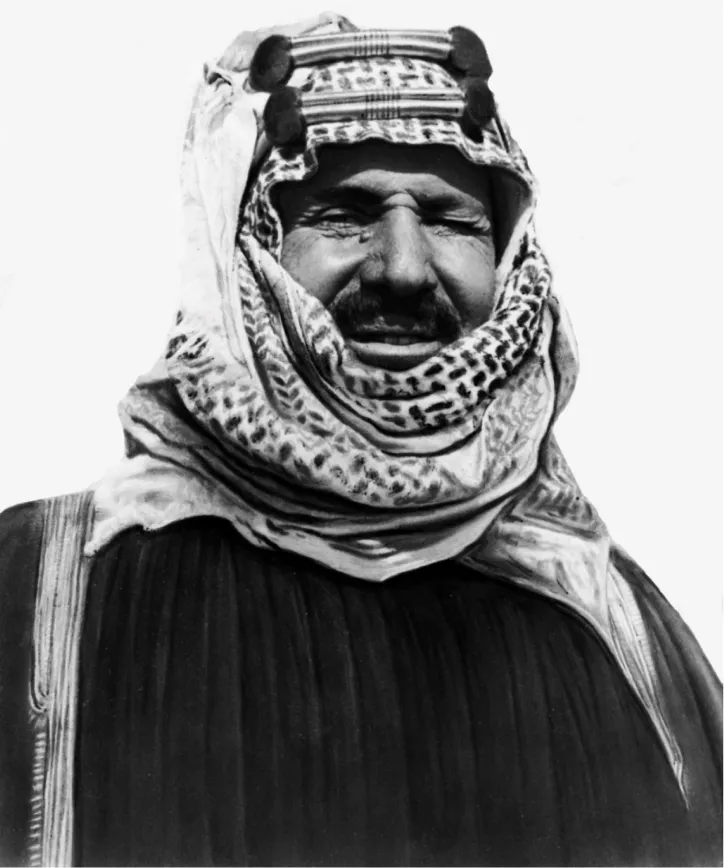

The king of Saudi Arabia, Ibn Saud, was six feet three inches tall and made an impression both by his height and by his air of command. Then in his fifties, he was still a handsome man apart from a blotch across the left eye due to neglected leucoma. ‘He has,’ an observer once wrote, ‘the characteristics of the well-bred Arab, the strongly marked aquiline profile, full-flesh nostrils, prominent lips accentuated by a pointed beard. His hands are fine with slender fingers [and he has a] slow sweet smile.’6 Not everyone was taken in by that smile however; as Ryan once remarked, ‘it was spoilt by his habit of switching it on and off almost mechanically’.7

Abdul Aziz ibn Abdul Rahman Al Saud, known to the British as Ibn Saud, in middle age. (source: Royal Geographical Society)

For those who had dealings with Ibn Saud, it was his apparent spirituality combined with an acute political skill that left a lasting impression. And although a deeply religious man – he took his duties as imam or spiritual leader of his people very seriously – he also took a close interest in foreign news programmes on the radio and avidly read translations of newspaper cuttings sent by his representatives abroad; thus he managed to keep himself up to date with international events. His political judgment was sound and he was rarely wrong: it was only in his later years that it weakened and became clouded by a degree of sentimentality.8

Now, in the Jedda of the 1930s, Ibn Saud was at the height of his power but, in the eyes of many foreign diplomats, his hold on power was weak. His throne had been forged by violence and violence threatened to break up his domain: live by the sword, die by the sword. The notion of a kingdom stretching from one shore of the Arabian Peninsula to another was a novelty and, since 1920, hardly a year had gone by without Ibn Saud having to put down an uprising somewhere in his kingdom.9

Ostensibly, however, Ibn Saud appeared strong and secure in his tenure. All this talk of oil was most propitious; and payments for an oil concession for Al-Hasa might refill his flagging coffers. His stipend of £60,000 from the British government had long since ended and the Great Depression had crippled his main source of income – taxes on pilgrims travelling to Mecca – as the number of pilgrims dropped from a peak of 127,000 in 1927 to 29,500 in 1932.10 There was little point in trying to persuade the king to curb his spending. Ibn Saud preferred to indulge his family rather than consider any stringent financial measures. His advisers were constantly scrimping, saving, and looking for new sources of income. The rental payments from an oil concession promised to go some way towards meeting the shortfall.

It was a situation that would have challenged the most competent minister, but the king’s advisers were unfazed. The confidential pen-pictures of leading Saudis compiled by British officials in Jedda make interesting reading today. The chief finance minister, Abdullah Suleiman from Aneiza in the Nejd, was described as an able and vigorous man. Born about 1887, he had started as a coffee boy and clerk before rising through the ranks of royal advisers to acquire complete control of all financial matters, and a certain grandeur besides. Ready and energetic in conversation and full of ideas about development, he showed great enthusiasm in the face of much hostility, envy and ill-natured criticism from his brother advisers. He was a keen fisherman and tireless traveller, his other pleasures including tobacco and the bottle.11

Yusuf Yasin, a Syrian refugee from Palestine, was the king’s confidential secretary, dogged negotiator and procurer of royal concubines. Born in about 1898, he was described as a pompous busybody, although his loyalty to Ibn Saud was never in doubt. He was ‘a difficult colleague with the small-mindedness of a Latakian grocer [he came from Latakia in Syria], but not unpleasant if taken with a pinch of salt’.12

There were other advisers such as Foreign Minister Fuad Hamza and Hafiz Wahba, the Saudi ambassador to London, who will figure later in our story. Despite their differences, these advisers had something in common: they had emerged from the dying embers of the Ottoman Empire with a strong sense of their Arab identity. Many were of Palestinian, Syrian or Egyptian origin, intelligent, enthusiastic, and they saw in Ibn Saud the opportunity to advance the Arab cause. Although the British underestimated and often denigrated them, one diplomat calling them ‘pinch-beck politicians’, such men were moving into positions of influence in governments across the Middle East.13

Amid this crowd stood an Englishman who, when at royal audiences (majilis), dressed in Arab robes: Harry St John Philby, known variously as ‘Jack’ or ‘Abdullah’. To some, Philby’s attempt to ingratiate himself with the king seemed a little absurd. The British minister in Jedda of the late 1930s, Reader Bullard, remembered seeing Philby in the majilis: a Muslim convert who imitated the Arabs by preceding every remark addressed to the king with the words ‘God prolong your life!’, Philby wore only sandals on his feet when all the other courtiers were in socks and slippers and even the king wore socks with ‘Pure Wool. Made in England’ on the soles.14

Philby had first arrived in Saudi Arabia as a British political officer with a brief to keep Ibn Saud ‘on side’ during the Great War. He returned to Saudi Arabia after the war as a special adviser to the king. Converting to Islam in 1930 had opened doors and enabled him to follow Bertram Thomas’ achievement of crossing the great sand desert, the Rub al-Khali or Empty Quarter. According to one British diplomat, Philby’s main purpose in life was to establish that the British were aligned with the forces of darkness. Another referred to him as ‘that Muslim renegade’.15 Yet, in 1932, Philby’s star was rising with the Saudis and his links with the ruling family made him attractive to a foreign company wanting to do business in the kingdom.16

Socal was an outsider to the Middle Eastern oil business. Based in San Francisco, the company was ‘crude-short’, meaning that it had limited access to supplies of crude oil. In response to domestic fears that American oil reserves were rapidly depleting, it had taken up the post-war challenge of seeking new sources of oil abroad. In 1920 it had set up a division specifically to look for new oilfields, sending geologists worldwide and spending $50 million in the process.17

As a foreign company seeking to operate in Saudi Arabia, Socal faced huge obstacles. It had no experience of Saudi Arabia and was unsupported by an American diplomatic presence in the country. It was unable to gain direct access to Ibn Saud and his advisers, and the lack of modern communications made it impossible to negotiate from a distance. In this situation, Philby was the perfect fixer.

In February 1933 a Socal delegation arrived in Jedda and checked in to the Egyptian Hotel, recently upgraded to a ‘government institution principally for high-class pilgrims’.18 Lloyd Hamilton, an astute property lawyer with no Arabic, soon abandoned the hotel and decamped with his wife to Philby’s house at the Beit Baghdadi. This was hardly any better, a rickety old building where the shutters were drawn all day to keep out the flies. Karl Twitchell, a mining engineer assisting Socal, and his wife were old desert hands and found the zinc baths and sand closets of the Egyptian quite tolerable.

IPC was much better placed than its rival, for it already had more oil than it knew what to do with. Since striking oil at Baba Gurgur in 1928, the company had made massive oil discoveries in Iraq. The company’s representative in Jedda was Stephen Longrigg, the archetypal English gentleman, tall, debonair, aloof, wearing a Panama hat and sporting a monocle. A member of the company’s Land and Liaison Department in Haifa, Longrigg’s skill as an Arabic speaker marked him out as an ideal negotiator of oil concession agreements with Arab potentates. He was accompanied by Sulaiman Mudarres, a young Syrian Muslim educated at Oxford, and they lodged in the Grand Hotel. As Ryan wryly observed, ‘we really now need a separate hotel for concession hunters’.19

* * * * *

Despite Socal’s oil strike in Bahrain, prospecting for oil on the Arabian mainland was still a massive gamble. With hindsight, this seems absurd, since Saudi Arabia today is the largest oil producer in the world. But in 1933 it was an entirely different matter, since no one really knew if there was oil in Arabia, let alone in the eastern province of Al-Hasa. Indeed, before oil flowed to the surface at Bahrain, the consensus of geological opinion had been that there was no commercial oil in Arabia.

Socal had a report from Karl Twitchell, following his visit to the province, stating that he had found oil seepages there. The report was not disclosed to Longrigg, who considered the concession a ‘pig in a poke’. The geological theory underpinning Saudi hopes of finding oil was, in his opinion, ‘somewhat naïve’, and the rationale for taking on the concession appeared to be exceedingly weak.20

But there was more to it than that. Socal’s discovery in Bahrain threatened IPC’s monopoly of oil in the Middle East. In the longer term, if oil was found in large quantities in Arabia, it might undercut prices and undermine IPC’s position in Iraq. The company’s aim was tactical – it intended to block Socal’s ambitions in the region by getting the Hasa concession and sitting on it. IPC executives did not want to explore Al-Hasa province, only to have the right to explore it: this was the ‘dead hand of IPC’ that would so infuriate Ibn Saud and his advisers.21

In one sense, however, IPC’s participation suited the Saudis since it brought an element of competition to the proceedings.22 The Saudis wanted a loan of £100,000 (£6 million today) in gold along with rental and royalty payments. The company replied with an offer of £5,000, which the Saudis rejected out of hand. The Americans countered with a better offer and Longrigg, suffering in the oppressive climate and pining for a boat back to Haifa, telegraphed London for further instructions.

An enervating heat settled over the town. With nothing else to do but wait, the parties shuffled back to their lodgings and made the best of their situation, trying to alleviate the boredom by writing up their notes and composing letters home. Meanwhile, Abdullah Suleiman would travel to Mecca, the headquarters of th...