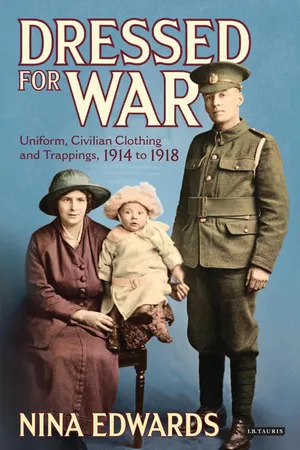

![]()

1 THE PRELUDE

As the state of war gathered momentum across Europe, the step dancer leans back against a curtained window, the light of a new age like a halo surrounding her. The painting was shown at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1918, yet it is an image of optimism at the war’s outset,1 with striped green silk taffeta iridescent harem trousers, recalling Amelia Jenks Bloomer’s enthusiasm for the eponymous loose trousers gathered at the ankle and worn under a short skirt, which had become briefly fashionable for ladies’ bicycling in the 1850s. The woman in the painting wears a white blouse rather low-necked and feminine, in soft Pierrot-like folds. The hair is shingled, and on her feet are ballet slippers and white stockings, in homage to the costumes of the Ballets Russes, so recently arrived in London from Paris. This is the self-portrait of Madeline Green, a young middle-class English artist from a comfortable London suburb, and she looks out at us conscious of the effect her version of the exotic demands. It is daring, but not too daring. The mood suggests something of the Perfect Summer Juliet Nicolson evokes,2 of indolent pleasure heightened by a vague sense of excitement ahead, of the aristocracy in tennis whites or toying with a croquet ball, too lazy to play in the late summer heat, bored but expectant.

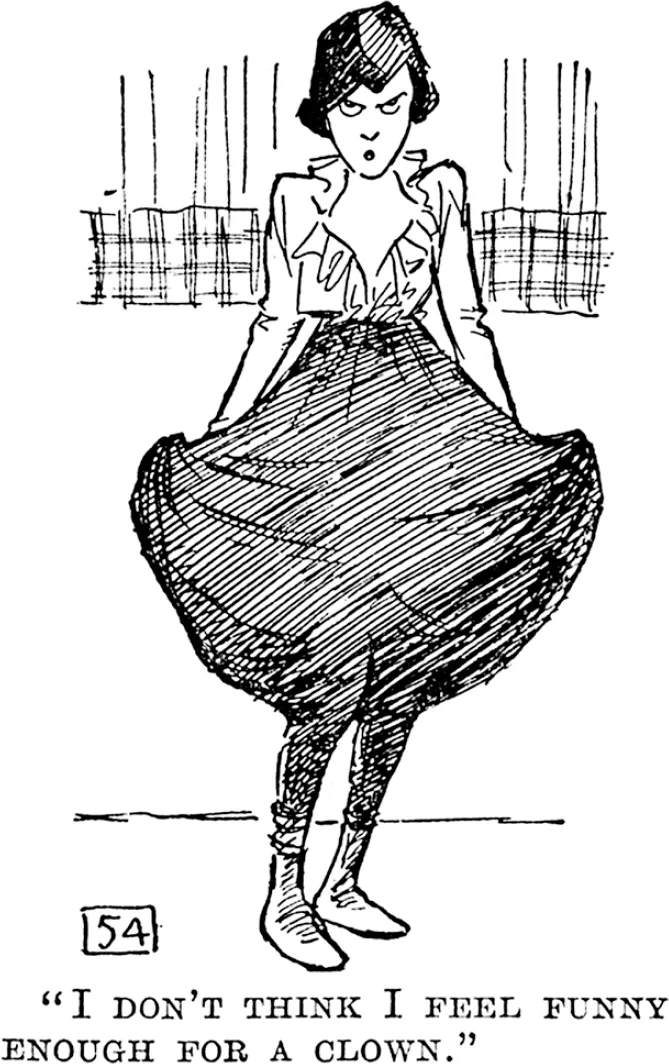

Punch magazine, with its humorous often satirical approach, lampooned The Step Dancer from its high-status, male viewpoint, in a cartoon where the gentle gaze has turned shrewish, her stockings bagged around bony ankles and ungainly flat feet – with a deeper décolleté revealing a scrawny, hollow chest.3 The message seems to be that pre-war modern girls are sexually uninviting and not remotely challenging.

A generation before and fashionable young women were tightly laced into steel framed corsets. The S-bend corset created a smoothly proffered mono-bosom and a tiny waist, that so-called symbol of beauty and femininity, exaggerating further the arching, bustled behind. Then, in a kind of deliberate opposition, she was buttoned primly to the neck, at least for daywear. Like Edna Pontellier in The Awakening, women’s clothes are both forbiddingly upholstered and yet give the impression of vulnerability ‘with a fluffiness of ruffles … [and] draperies and fluttering things’.4 In John Singer Sargent’s paintings, women with their opulent Gibson Girl curves, their rich brocades and velvets, seem larger than life. Hats were borne vast and festooned with flowers, swathes of curling feathers and veils of tulle, to balance out the hourglass figures beneath. In the evening women’s chest and arms were suddenly laid bare, albeit unapproachable as marble statuary, in flimsy chiffon fabrics over the whalebone and steel corsets beneath, ‘in obedience to the decorative instinct which calls for fine clothes in fine surroundings … a surface of rich tissues and jewelled shoulders’.5

This contrast is in some counterpoint to uniform, which seeks to make bodies appear invincible, even though beneath the carapace of hardwearing fabric, the leather and tough webbing belts and carriers, the stout boots and metal helmets, the tender flesh remains.

The transformational aspect of uniform might not always succeed in persuading the onlooker as to the wearer’s character. An astute Piete Kuhr at 14 years old, courted by a dashing lieutenant in German Flying Corps splendour, considers his shoulder-pads and thinks that ‘without his finely tailored uniform he might not look so handsome’. Some months later, however, she is disappointed by the lacklustre sight of her brother in the new less tailored field dress, ‘Was this Gil? … in loose-fitting uniform with concertina trousers, thick boots and crazy-looking helmet? And his lovely soft, dark hair cut short? Oh Gil, my brother Willi!’6

5. Punch’s view of The Step Dancer.

The turn of the twentieth century was an age of richly detailed adornment for women – for those who could afford it – everything trimmed with lace, ruffles, velvet and fringe. Women’s clothing might be elaborately embroidered in deference to the Aesthetic Movement, which was antimodern in its outlook, its influence extending across Europe and the United States (which from now on will be referred to as America). Materials for those of means were extravagant and often impractical, with fine wool cashmeres and even shantung silk for day, figured cotton and silk muslins in summer and gossamer tissue and chiffon for evening. Longer-lined, boned bodices with more fitted skirts eschewed the need for layered petticoats, a glimpse of which had for so long suggested a hidden female vulnerability beneath. However, the design of women’s clothes continued to constrict and many of the fabrics were deliberately high maintenance. Washable fabrics were associated with those of low status, who worked for a living.

6. Satin evening dress by Lucile, c.1912, trimmed with chiffon and machine-made lace, silk velvet, lined with grosgrain and whalebone. This was described by the designer as ‘so lovely that [it] might have been worn by some princess in a fairytale’, Discretions and Indiscretions, 1932.

Pre-Raphaelite Greco-Roman draped styles of the Arts and Crafts Movement appeared to give women more room to breathe, though it is significant that in many cases corsets continued to be worn unseen, Alexandra Palmer describing Jane Morris, for example, as having ‘no lacing or corset visible’.7 It suggests that for many it was the appearance of having discarded traditional underwear that mattered, rather than the expression of genuine change, returning to some romantic notion of medieval simplicity. With their flowing lines and less demanding underpinnings, women’s sumptuous dress still expressed either conspicuous wealth and/or created an illusion of an imagined past romantic age. Stella Newton describes the hand embroidery, so valued on artistic clothing, as not only inexpensive to produce at home, but significantly here that ‘it could be seen to be of very little cost’ (my italics).8 The Arts and Crafts woman might ape medieval homespun accomplishment, but in reality her clothing was still made by a dressmaker in the main, a little light embellishment the extent of her involvement. When women did take on the making of their garments, then it tended to be as a hobby, supported by the wealth of a supporting male breadwinner.

A. S. Byatt depicts a Fabian circle in the late 1890s9 playing at homemade costume as artistic expression, but underpinned by the confidence bred of class and economic security. One household takes the style too far. Seraphita Fludd has become eccentric rather than artistic with her fanciful dressmaking, betraying the moral deviation within her close family, coupled with its financial decay. C. Willett Cunnington reads a general moral decay into the turns of fashion at the dawning of the new century:

Were the Suffragette Movement and its contemporary, the Hobble skirt, antagonists or queer products of a common impulse? In the darkening twilight of Class Distinction shadowy new forms were picturing the shape of things to come, the fashions and the events so mingled that we can hardly comprehend the one without the other.10

A connection is being made here between what appears to liberate women’s clothing, and fashions that deliberately impede natural movement. Rational or reformed dress codes at the 1907 International Women’s Socialist Conference in Stuttgart, for instance, were wide ranging, from Liberty-style loose robes to much plainer dress among some German and Dutch participants, and the British novelist E. Nesbit.11 The fashion for these so-called new forms of dress was short-lived, Valerie Steele putting its failure to catch on down to women’s fear of looking fat.12 Cunnington describes a persistent anxiety as representing ‘a pathetic reluctance to abandon all the devices of sex-attraction’. 13 He has little time for the ‘sensible’ clothing worn by many suffragettes, although the mainly well-to-do women drawn into the movement’s ranks were often in fact fashionably got up, some pictured in what appears to be hobble skirts and huge, impractical and elaborately confectioned hats. When Emily Wilding Davison went under the king’s horse at the 1913 Derby, she was kitted out in a soigné black tailored suit with a brooch in the purple, green and white colours of the movement, to match her splendid protest banner. Earlier photographs show her in de rigueur feather boa and broad-brimmed hat.

The relative colourfulness and variety in female clothing, as opposed to male solemnity, was a distinction that applied more to the upper and emergent middle classes, with the means to afford the impractical. For the working classes, for servants, shop, factory and office workers and for those who worked in the field – in America and particularly in less-industrialized Europe – for all those who laboured at cottage industries while caring for their offspring in the home, fashion was largely unaffordable and clothing was more often than not mainly plain and dark enough to forgive dirt and wear. Even a cotton print was a considerable extravagance, to be carefully budgeted. A fortunate lady’s maid might inherit her mistress’s cast-offs, and used clothing was traded down, but otherwise colour, pattern and choice of fabric was limited.

It took war to grant women across the board an opportunity to more fully engage in new shopping and fashion opportunities. The percentage of women working was not significantly higher during the war, 32 per cent of French women employed at the beginning of the war as opposed to 40 per cent in 1918, 26 per cent mounting to 36 per cent in Britain, and because of the sharp rise in women’s employment in the two decades preceding the war, an actual decline in Germany. 14 Nonetheless it was the change in the nature of women’s work and the resultant rise in women’s wages that gave them more spending power. Women gained greater economic clout and thus a measure of autonomy to access fashion. Moreover, there was less stigma attached to women of all classes aspiring to fashion. Working collaboratively as never before, thrown together in armaments factories for example, in relation to both women’s attitudes at home and those working near the frontline, women’s dress across class boundaries began to look more alike.

As for men, the elaborate male dress of the eighteenth-century male, the velvet and silk coats, the lace furbelows and embroidered waistcoats, gorgeously painted and jewelled passementerie buttons, sparkling buckles and exquisite pale silk stockings, had given way to the nineteenth-century dandy, all refined monochrome in figure-hugging trews, carefully tied cravat and elegant tailoring. Now, in the first decade of the twentieth century, the Great Male Renunciation of display was fully entrenched. Men had retreated into their now familiar dark uniformity, so that it was difficult to distinguish class, status or even income from dress alone, plain dark clothing of superior quality making very much the same passing impression as the mass-produced.

Sarah Frantz, discussing Jane Austen’s soberly dressed and reticent heroes, suggests that this denial of sumptuous dress demonstrates ‘a similar renunciation15 in men’s ability to express their emotions’. She argues that ‘men’s dress, in order to symbolize power and self-control, was supposed to be unremarkable’ recalling Beau Brummell’s view that it was not seemly for a well-dressed man to turn heads. Any outward display might suggest weakness or effeminacy, and it is only lately that men have been able to express emotion in public without embarrassment, even on occasion appearing to raise their status as men thereby. At the outbreak of the First World War men were already largely dressed to avoid individual differentiation, as they sought to square up to the dangers ahead without either the show or even the experience of fear. To be proper men they needed to put aside self-interest: ‘Steeled to suffer uncomplaining.’16

Uniforms are about the ‘comfort and vanity of belonging’;17 war is a context where it is essential to work together to a common end. A Frenchman scorns German pride in uniform, ‘Everywhere I saw blind adoration of the uniform, overwhelming joy in wearing it,’ and dismisses German soldiers as ‘a fine army of automata!’18 However, as a prisoner of war (POW) he is evidently concerned to maintain his own uniformed appearance and takes delight in describing in his diary its many permutations amongst the French and Russian prison inmates.

The adoption of men’s service uniform and its myriad adaptations, and the range of uniforms developed for women during the war, were important factors in the preparation of resilience under threat. Uniforms affected how people saw themselves and how they came to fee...