![]()

Chapter I

Guru Nanak and the Origins of Sikhism

Sikhism began with the birth of Guru Nanak in 1469 at Talwandi, a village in north India, which is now in Pakistan. There is not much factual documentation on the founder Guru, but in spite of the lack of this, Guru Nanak’s biography is strongly imprinted in the collective memory of Sikhs. There are three vital sources for his life: the Janamsakhi narratives; the ballads of Bhai Gurdas; and the Sikh scripture. Together they provide a vibrant portrait of his life and teachings. For the more than 23 million Sikhs across the globe,1 Guru Nanak is the starting point of their heritage, as most begin their day by reciting his sublime poetry. Sikh homes and places of business display his images. Guru Nanak is typically represented as a haloed, white-bearded person wearing an outfit combining Hindu and Islamic styles; his eyes are rapt in divine contemplation, and his right palm is imprinted with the symbol of the singular Divine, Ikk Oan Kar. This chapter turns to the three traditional literary sources for an understanding of the person of Guru Nanak. (For his visual depiction, see Chapter VIII, on Sikh art.)

Janamsakhi Literature

Shortly after he passed away, Guru Nanak’s followers wrote accounts of his birth and life. These are the first prose works in the Punjabi language, using the Gurmukhi script. They are called the Janamsakhi, from the Punjabi words janam, which means ‘birth’, and sakhi, which means ‘story’. Through the years, they have been passed down in a variety of renditions such as the Bala, Miharban, Adi and Puratan. The dominant motif of the Janamsakhis is not chronological or geographical accuracy. As an eminent Sikh historian explains: ‘These accounts were written by men of faith. They wrote for the faithful – of a theme, which had grown into their lives through the years as a real, vivid truth. Straightforward history was not their concern, nor was their description objective and conceptual.’2

The pattern of mythologizing is rooted in the Indian culture, and the Janamsakhi authors would have been familiar with ancient and medieval Indian literature. Narratives from epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, and from the Puranas, have been told, remembered and retold for centuries. A mixture of mythology, history, philosophy and geography, these texts narrate events which actually happened; thus they are known in India as Itihasa (Sanskrit for ‘history’). By the time that the Janamsakhis came into circulation, miraculous stories (mu’jizat) about Prophet Muhammad and about Muslim saints (karamat) had also become widespread in the Punjab through Sufi orders. The Janamsakhi writers were influenced by what was current in their milieu, and they took up the pattern in which great spiritual figures were understood and remembered.

Despite the personal loyalties and proclivities of their various authors, the Janamsakhis invariably underscore the importance and uniqueness of Guru Nanak’s birth and life. In the language of myth and allegory, they depict the divine dispensation of Nanak, his concern for kindness, social cohesiveness, and his stress on divine unity and the consequent unity of humanity. Some of the stories incorporate verses from Guru Nanak’s works to illuminate his theological and ethical teachings in a biographical framework. The quick and vigorous style of the Janamsakhis lent itself easily to oral circulation, and they became very popular. They continue to be read and told by both the young and the old. At night in many Sikh households, parents and grandparents read them as bedtime stories to young children. They have also been painted and brightly illustrated (which will be examined in Chapter VIII). The Janamsakhis provide Sikhs with their first literary and visual introduction to their heritage, and continue to nurture them for the rest of their lives.

They begin with the illustrious event of Nanak’s birth to a Hindu Khatri couple. His father, Kalyan Chand, worked as an accountant for a local Muslim landlord; his mother Tripta was a pious woman. In their central concern and luminous descriptions, Nanak’s birth narratives have a great deal in common with those of Christ, Buddha and Krishna (collected by Otto Rank in his study, The Myth of the Birth of the Hero).3 The prophets told Buddha’s father, King Suddhodhana, that his child would be a great king or a great ascetic. The three Wise Men followed a bright star to honor the baby Jesus, born in a stable in Bethlehem. And just as that stable was marked by the bright Star of Bethlehem, the humble mud hut in which Nanak was born was flooded with light at the moment of his birth. The gifted and wise in both the celestial and terrestrial regions rejoiced at the momentous event and bowed to the exalted spirit, which had adopted bodily form in fulfillment of the Divine Will. But unlike the ‘virgin’ births of Sakyamuni and Jesus, Nanak had a normal birth. The midwife Daultan attests to Mother Tripta’s regular pregnancy and birth. That Tripta’s body is entrusted to a Muslim Daultan symbolizes yet another significant fact: the respect and the close connection Nanak’s family had with the adherents of Islam. The Janamsakhis show Tripta happily holding the baby in her arms, while Daultan proudly and excitedly reports that there were many children born under her care, but none so extraordinary as baby Nanak. Affirmation of the natural powers of conception, gestation and birth underlie their rejoicing.

The Janamsakhis continue to offer a substantial sketch of Nanak’s life. When he grows up, Nanak becomes discontented with the existing norms. He is in conflict with his father, who wants his only son to succeed both financially and socially. The young Nanak does not like formal schooling. He has a contemplative personality and spends most of his time outside, tending the family’s herd of cattle, conversing with wayfaring saints and Sufis, and devoting his time to solitude and inward communion. Nanak is close to his sister, Nanaki.4 When he grew up, he went to live with Nanaki and her husband Jairam in Sultanpur, and worked at a local grocery shop. Later, his marriage was arranged with Sulakhni, and they had two sons, Sri Chand (b. 1494) and Lakhmi Das (b. 1497).

It was at Sultanpur that Nanak had a revelatory experience into the oneness of Reality (analyzed below). As the Janamsakhis recount, with his proclamation ‘There is no Hindu, there is no Musalman’, Nanak launched his religious mission. Thereafter he traveled extensively throughout India and beyond – spreading his message of Divine unity, which transcended the stereotypical ‘Hindu’ and ‘Muslim’ divisions of the time. During most of his travels, his Muslim companion Mardana played the rabab while Guru Nanak sang songs of intense love addressing the ultimate One in spoken Punjabi. The direct and simple style of Guru Nanak’s teaching drew people from different religious and social backgrounds. Those who accepted him as their ‘guru’ and followed his teachings came to be known as Sikhs, a Punjabi word which means ‘disciple’ or ‘seeker’ (Sanskrit shishya; Pali sekha).

Guru Nanak eventually settled in Kartarpur, a village he founded by the banks of the River Ravi. A community of disciples grew around him there. Engaged in the ordinary occupations of life, they denied ascetic practices and affirmed a new sense of family. Their pattern of seva (voluntary service), langar (cooking and eating irrespective of caste, religion or sex) and sangat (congregation) created the blueprint for Sikh doctrine and practice. In his own lifetime, Nanak appointed his disciple Lahina as his successor, renaming him Angad (‘my limb’). Guru Nanak died in Kartarpur in 1539.

This biographical framework is drawn up in miraculous detail. The Janamsakhis depict scenes in which dreadful and dangerous elements of nature either protect Nanak (such as the cobra offering his shade to a sleeping Nanak) or are controlled by him (with his outstretched palm, Nanak stops a huge rock that was hurled at him). They depict his divine configuration: at his death, the shroud is left without the body; flowers are found instead of Guru Nanak’s body; and both Hindus and Muslims carry away the fragrant flowers – to cremate or bury according to their respective customs.

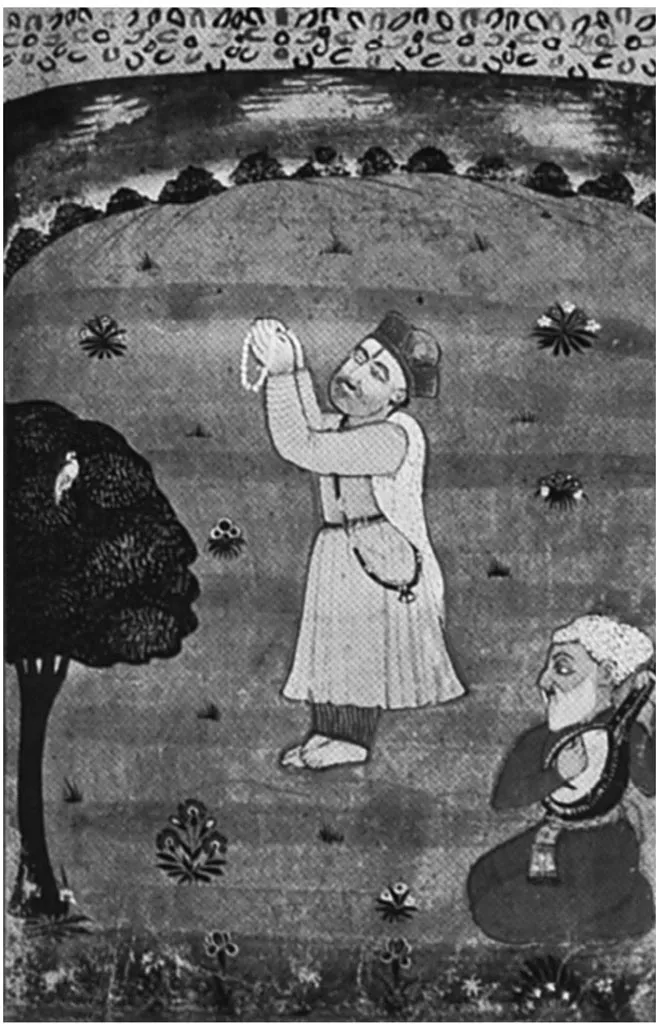

They repeatedly portray Guru Nanak denouncing formal ritual, often with great wit and irony. During his travels, Nanak visits Hardwar, the ancient site of pilgrimage on the River Ganges. When he saw some priests sprinkling water to the rising sun in the East, Nanak started sprinkling water to the West. The priests found his actions sacrilegious. So when they asked him who would benefit from his splashing water to the West, he questioned them in return. The priests responded that they were offering oblations to the spirits of their dead ancestors. Nanak then continues his procedure with even greater vigor. Through this dramatic sequence he makes the point that, if water sprinkled by priests could reach their dead ancestors, surely his would reach the fields down the road and help his crops.

This pedagogical pattern recurs frequently in the Janamsakhi narratives. Nanak twists and overturns the established ritual codes in a way that challenges people’s innate assumptions, and orients them toward a new reality. The numerous miracles associated with him are not a means of amplifying his grandeur, but rather, they serve as lenses through which his audience can interrogate the inner workings of their own minds. When Nanak goes to Mecca, for example, he falls asleep with his feet towards the Ka’ba. The Qazi in charge gets upset because of the irreverence shown by the visitor. However, Nanak does not get ruffled. Rather than contradict him, he politely asks the Qazi to turn his feet in a direction he deemed proper. But as Nanak’s feet are turned, so does the sacred Ka’ba. There is no need for readers to consider it a historical fact; the motion of circularity simply shatters rigid mental formulas. That the Divine exists in every direction and that internal religiosity cannot be expressed externally are effectively communicated. Narratives such as this dislocate conventional habits and linear structures of the readers, and whirl them into a vast interior horizon.5

In an oft-quoted account, Nanak refuses to participate in the upanyana initiation – the important thread ( janeu) ceremony reserved for ‘twice born’ Hindu boys (from the upper three classes). The Janamsakhis point to a young Nanak disrupting this crucial rite of passage that had prevailed for centuries. His denial is framed within an elaborate setting arranged by his parents. A large number of relatives and friends are invited to their house. Pandit Hardyal, the revered family priest, officiates at the ceremonies. Pandit Hardyal is seated on a specially built platform purified by cow-dung plaster, and the boy Nanak is seated across, facing him. Pandit Hardyal lights lamps, lights fragrant incense, draws beautiful designs in flour-chalk and recites melodious mantras. When the priest proceeds to invest the initiate with the sacred thread ( janeu), Nanak interrupts the ceremonies, questions him as to what he is doing with the yarn, and refuses to wear it. At this point, the narrative juxtaposes Nanak’s criticism of the handspun thread with his ardent proposal for one that is emotionally and spiritually ‘woven by the cotton of compassion, spun into the yarn of contentment, knotted by virtue, and twisted by truth’.6 Rather than being draped externally, the janeu becomes an internal process. ‘Such a thread’, continues Nanak, ‘will neither snap nor soil; neither get burnt nor lost’. Nanak’s biography and poetry are thus blended together by the Janamsakhi author to illustrate his rejection of an exclusive rite of passage. A young Nanak interrupts a smooth ceremony in front of a large gathering in his father’s house so that his contemporaries could envision a different type of ‘thread’, a different ritual, a whole different ideal. There are many such vignettes in which Nanak vividly dismantles the prevailing societal hegemonies of caste and class, and reinforces an egalitarian human dimension.

The Janamsakhis are particularly significant in introducing the earliest women mentioned in Sikhism. They may not fully develop their individual characters, and reveal them only in so far as they are related to the Guru. Yet even in their rudimentary presentations, the authors highlight the subtle awareness that the women possess. Mata Tripta is a wise woman who understands her son and can see into his unique personality – much more so than his father. The midwife Daultan is struck by the extraordinary qualities of the child she delivers. Like Mary Magdalene, who was the first woman to have witnessed the resurrection of Christ, sister Nanaki is the first person to recognize Nanak’s enlightenment. Only Sulakhni’s role is ambiguous, as if the authors did not quite know how to deal with her. As the wife of the founder of the Sikh religion, where was she? What was her relationship with her husband? How did she feel when he left her with their two sons and went on his long journeys?

The north Indian soil was rich with saints from various Hindu denominations, just as it was with the different orders of Sufism, Buddhist schools and Jain monks. With their holy presence, their devotional outpourings, and their message of love and charity, leaders and common folk from different religious backgrounds and ethnicities created a vibrant environment. The Janamsakhi literature depicts a pluralistic Nanak, who engages meaningfully with people of different faiths. Full of respect and with no acrimony, he discusses and discourses with them. There is ...