![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE UN COLLECTIVE SECURITY

ACTION, JUNE–OCTOBER 1950

On the night of 24–25 June 1950 frantic activity was not only taking place in Korea and Washington. That night in UN circles New York lived up to its reputation as the city that never sleeps. At approximately midnight UN Secretary-General Trygve Lie was awoken at his home by a telephone call from US Assistant Secretary of State for UN Affairs John Hickerson. In a brief and agitated conversation Hickerson informed the shocked Secretary-General of the reports Washington had received regarding the North Korean invasion and the indications that this was more than another border clash. Lie immediately requested a report from UNCOK on what had taken place. At 2 a.m. US Deputy Permanent Representative to the UN, Ernest Gross, then made a formal request for an Emergency Session of the Security Council. Realizing the gravity of the situation Lie immediately obliged, setting a meeting for 2 p.m. that day. While the Secretary-General returned to bed for a few more hours of sleepless rest, hurried phone calls were made to the missions of those member states represented on the Security Council who relayed the news to their respective governments. Even though the morning newspapers were published too early to report the outbreak of the Korean War, by daybreak word of the North Korean invasion had spread across the globe.1

Over the following two weeks the Security Council established the UN’s first collective security action. The driving force in this process was the US government. It took the lead in formulating the various draft resolutions that were adopted while the US delegation dominated proceedings in New York. For the most part the Commonwealth members played a passive role at the UN during this opening phase of the conflict, giving their unquestioned support to US policy. India was the partial exception, only temporarily abandoning its position of neutrality to give tacit approval to the Korean action. While the Old Commonwealth members did coordinate their response to the call for military assistance, no comparable effort was made to bring about a united Commonwealth position at the UN. Furthermore, the Commonwealth members had no significant desire to constrain Washington’s policy since they generally agreed with it and had no alternative suggestions to make.

The Commonwealth remained disunited because none of the necessary conditions for unity were present. To begin with, while its members saw the North Korean invasion as a threat to global peace, they strongly believed that the UN decision to intervene was a necessity and not one that would in itself lead to an escalation of the conflict. The Korean action was intended to repel aggression and throughout the first months of the conflict all the Commonwealth members except India thought it very unlikely that either the Soviet Union or China would become directly involved. The other Commonwealth members, therefore, saw no need to try to constrain US policy at the UN, especially once military fortunes improved. Nor did many opportunities exist to coordinate a united policy. Only Britain and India were members of the Security Council and they had little time to consult with each other, let alone the other Commonwealth governments. Even when a number of key Commonwealth personalities assembled for the Fifth General Assembly they preferred to support rather than challenge the US position. In addition, the Truman administration consistently showed little willingness to consult with the Commonwealth members let alone bend to their wishes. Washington considered Korea its responsibility and it would not have altered its position even if the Commonwealth had raised objections.

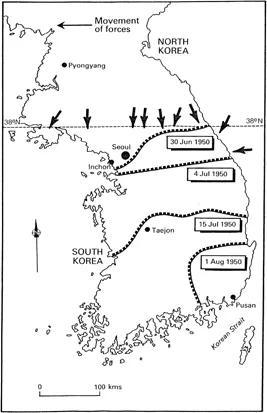

Figure 1.1 The North Korean advance, June–September 1950.

Source: MacDonald: Korea, p. 202.

But to understand the course of the early UN debate on Korea fully it is first necessary to set the context by outlining the military situation on the ground, relevant domestic developments in the United States and each of the Commonwealth countries, and international events connected to the Cold War during this period.

Military situation

Within days of their invasion, the NKPA had won a number of victories, capturing Seoul, against the numerically inferior ROKA that had only received light arms from the United States for fear Rhee intended to launch an assault of his own. Even the intervention of US air and sea forces on 27 June 1950, under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP) in Japan and Commander-in-Chief of US Forces in the Far East, did little to slow the North Korean advance. Three days later the US Eighth Army, under the UN banner and commanded by Lieutenant-General Walton Walker, began arriving from Japan. Bolstered by his sense of both destiny and racial superiority, MacArthur was confident that the North Koreans would be easily defeated. But over the following weeks the UN forces in Korea were overwhelmed and pushed back. The Eighth Army’s ineffectiveness was the result of post-1945 cuts in the military budget which had produced an under-strength, poorly-equipped, trained and officered force. After nearly five years of occupation duties in Japan, these American soldiers were also ill prepared for combat.

Yet just as it appeared that the Eighth Army might be driven out of Korea the tide slowly began to turn. A strong defensive position was hastily established in the southeast of the country in what became known as the Pusan Perimeter. Behind this shortened line the ROKA was able to regroup while the Eighth Army was greatly strengthened by the arrival of reinforcements from the United States. The port of Pusan was also crucial in bringing in supplies from Japan. In addition, US air, naval and artillery superiority was successfully employed to interrupt the overextended North Korean supply network. Then in late August 1950 the first contributions from other UN members arrived. Throughout the following weeks the fighting was brutal, but slowly the UN position improved as the North Korean forces tired, and many of its experienced soldiers and better equipment were lost.

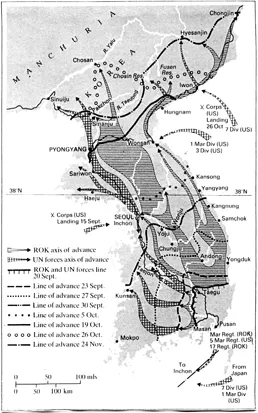

The crucial turning point of the early conflict then took place in mid-September 1950. MacArthur, now Commander-in-Chief of the UN Command (UNC), had long called for an amphibious counteroffensive at Inchon near Seoul. The Department of Defense, however, opposed this suggestion on the grounds that Inchon had formidable natural and manmade defences and had treacherous tides and currents. Still, on 23 August at a meeting in Tokyo, MacArthur convinced the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the wisdom of his plan by stressing the element of surprise. On 15 September the landings took place and went spectacularly well with little resistance being encountered. A week later the US X Corps under Major-General Edward Almond moved on Seoul. Despite continued fighting Almond claimed the city’s liberation three days later. Meanwhile, the UN forces, including the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade, staged a massive breakout from the Pusan Perimeter, using its air and naval forces to sever the enemy’s supply lines. By the end of the month the North Korean forces had been decimated and pushed back to the 38th parallel.

The question now facing the US government was whether to pursue the enemy north over the former border. The Pentagon and the State Department had some apprehensions that this might lead to Soviet or Chinese intervention in the conflict. But intelligence estimates stated that this was very unlikely and MacArthur was tentatively granted authority to employ forces north of the 38th parallel. As a result, some ROKA units did cross the frontier but neither Washington nor Tokyo wished to employ non-Korean forces in North Korea without UN legitimization. As will be discussed in detail below, on 7 October 1950 the General Assembly then took the crucial decision allowing the UN to unify Korea by force. Before this happened MacArthur had sent a message to the North Korean Command calling on their forces to lay down their arms, cease hostilities and cooperate with the UN efforts to unify and rehabilitate Korea. Nevertheless, UN forces almost immediately crossed the 38th parallel and the enemy was quickly overrun. By late October 1950 US troops had reached the Yalu river despite Truman’s explicit instructions to only use ROKA units in the frontier region. The Korean War appeared to be drawing to a close.2

Figure 1.2 The UN Command’s counter-attack, September–October 1950.

Source: Lowe: The Origins of the Korean War, p. 269.

Domestic developments

The first four months of the Korean War witnessed the most tumultuous period of Truman’s presidency to date as he struggled to sell the ‘police action’—as he had labelled the UN intervention in Korea, to circumvent a Congressional declaration of war—to the American people. The public’s initial response to the decision to intervene in Korea had been generally enthusiastic and the majority of the population saw the conflict as a necessity to prevent Soviet aggression elsewhere. The public perception of the UN also improved dramatically with the successful establishment of the organization’s first collective security action. But the popularity of the war soon declined with the early military setbacks. Criticism mounted, especially from the right wing of the Republican Party led by Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, over the government’s handling of the conflict. A growing sense of uncertainty developed in Congress and the public domain as to why US soldiers were dying in a distant land of little strategic value. Moreover, the UN came under renewed attack since so few other members had contributed forces and the work of the Security Council had again become deadlocked following the return of the Soviet delegation. Nonetheless, the popularity of both the conflict and the UN radically improved following the Inchon landings and the military turnaround on the battlefield.3

Inside the administration, meanwhile, the Korean War created much friction. Acheson, a long-standing target of the Republican press in general, and Senator Joseph McCarthy in particular, became the butt of Grand Old Party (GOP)4 attacks as the mid-term election campaign heated up. Truman, however, remained loyal to his most trusted adviser. Acheson’s rival, Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson, however, was much more vulnerable. He was an easy scapegoat since he had aggressively overseen the military budget cuts ordered by Truman over the previous 18 months. By the middle of September Johnson’s position had become untenable and Truman forced him to resign. He was replaced by General George Marshall, the former Army Chief of Staff and Secretary of State, who was particularly close to Truman.5

A quite different relationship existed between Truman and MacArthur. The president appointed the general to lead the UN forces in Korea due to his experience, prestige, popularity, and because he was on the spot in Tokyo. But friction between the two men surfaced in late July 1950 when MacArthur made an unauthorized visit to Taiwan to consult with Chiang Kai-shek. Truman cautioned MacArthur for acting beyond his authority but, a month later, the general publicly criticized US policy in East Asia in a written statement to the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Truman reacted angrily and demanded that MacArthur withdraw his statement. Relations then remained strained until MacArthur’s military masterstroke at Inchon. Consequently, when they met for the first time at Wake Island on 15 October 1950, both men were cordial and MacArthur reassured Truman that neither the Soviet Union nor China would intervene to prevent the unification of Korea and that the war would be over by Christmas.6

In contrast to these US upheavals, the outbreak of the Korean War had a much less disruptive political impact in the Commonwealth countries. Generally, the Commonwealth governments, and their domestic audiences, did not believe that an act of aggression by such a small power as North Korea, looking to simply reunify the peninsula, could trigger a global conflict. Furthermore, they saw Korea principally as a US issue and they did not think it was their position to meddle too deeply. Yet in the Commonwealth countries a consensus view emerged that the Korean situation could not be ignored. Memories of appeasement were strong and the vast majority of Commonwealth governments realized that the Soviet Union lay behind the North Korean invasion. They thus agreed with the Americans that Moscow had to be taught that aggression would be resisted anywhere in the world. Support for the UN intervention, therefore, was widespread even if it led to few public outpourings of emotion. When it came to the question of sending ground troops to Korea, however, a number of prominent critics were opposed on the grounds that their countries could not afford to send soldiers to such a distant theatre. Nevertheless, post-Inchon these voices were soon hushed.7

Behind this moderate reaction to the Korean War was the fact that most Commonwealth governments were popular. St Laurent in Canada, Menzies in Australia and Holland in New Zealand had all been recently elected and their domestic and foreign policies enjoyed widespread support. Likewise, in India and Pakistan, Nehru and Liaquat Ali-Khan were enjoying periods of relative domestic stability and their respective leadership positions were secure. Britain and South Africa were the exceptions. In London, even though the Conservative opposition largely backed Attlee’s Korean War policy, the Labour government was in a precarious position. Since the February 1950 general election it held a majority of just five seats and had become increasingly divided over Bevin’s pro-American foreign policy. Unity prevailed in support of the initial UN intervention in Korea but the pre-existing fissures gradually widened following the decision to contribute British ground forces.8 The situation in South Africa was even more tumultuous as Malan continued to push through apartheid legislation in spite of much internal and external opposition. More than in any other Commonwealth country, Korea remained an extremely peripheral issue for South Africa.9

International situation

The eruption of the Korean conflict created immense international shockwaves. Although many governments shared US fears that the North Korean invasion might be a precursor to further acts of Soviet aggression, the US reaction only heightened these anxieties. On 27 June 1950 Truman issued a controversial statement announcing that the US Navy’s Seventh Fleet would be positioned in the Taiwan Strait. The President stressed that he was trying to prevent the PRC taking advantage of the situation in Korea to launch an invasion of Taiwan. Beijing...