- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

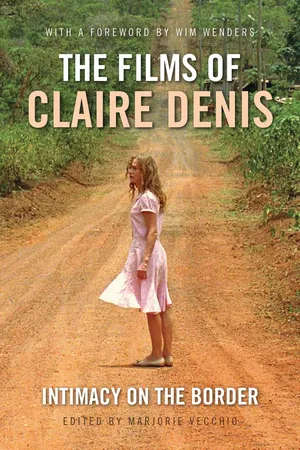

The films of Claire Denis probe the idea of global citizenship and trace the borderlines of family, desire, nationality and power. Her films, including Chocolat, Beau travail and White Material explore connections between national experience and individual circumstance, visualizing the complications of such dualities. Following a foreword by Wim Wenders, international contributors explore the themes she addresses in her films, such as kinship and landscape, neo-colonialism and New French Extremity. Original interviews with an editor, actor and two composers familiar with Denis's working style and with Denis herself, also reveal fresh facets of this intrepid filmmaker.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Films of Claire Denis by Marjorie Vecchio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Interviews

1

‘To Let The Image Sing’: Conversations with Dickon Hinchliffe and Stuart Staples

‘To Let the Image Sing’

Hearing the song ‘My Sister’ (1995) for the first time as she was shooting Nénette et Boni (1996), her absorbing account of a sister–brother relationship, Claire Denis had an immediate kindred feeling with the Tindersticks’ distinctive musical universe: the way Stuart Staples’ trembling baritone inhabits the brooding, slightly off-kilter space that the music creates, bringing out its characteristic mood of melancholy fragility. The band’s idiosyncratic approach could be described in terms of defamiliarisation and a kind of generic subversion – from ballad to bebop to Bossa Nova, familiar genres are revisited with simple melodic lines that are drawn out, repeated or distorted, alternatively turned into haunting leitmotivs or brought to the brink of dissolution.1

Similarly, Denis’s film worlds elicit an intangible sense of strangeness, at once intriguing and unsettling. Unconstrained by the requirements of tight plot and dialogues, her films take the form of slow-paced, careful explorations of relationships between characters and between characters and environments where, captured by the camera’s attentive gaze and rendered through meticulous sound compositions,2 even the most mundane of spaces, everyday objects or situations appear as more than mere prop or setting. Denis’s cinema is also a cinema of gestures and movements, of the melody drawn out by bodies circling around one another, gradually transforming as they move from one space to another. Together, music, sound and image offer this entrancing quality of something in suspension, caught between an indefinable sense of threat and a charmed wistfulness.

At the recent series of Tindersticks concerts based on the film scores, the band played beneath a cinema screen on which sequences from the films unravelled throughout. These performances not only beautifully emphasized a rare case of image–music symbiosis, but they also highlighted the remarkable formal achievement of Denis’s films – detached from the rest of the film but brought forth by the music, each sequence filled the screen with an inescapable power.

All of Denis’s feature films have been scored and performed by renowned musicians, testifying both to the director’s love of music and the openness of her filmmaking to heterogeneous references and to the appeal of her work to musicians. The Tindersticks are privileged collaborators, however: six of her films have been scored either by the band or by ex-Tindersticks musician and composer Dickon Hinchliffe. The Tindersticks have signed the scores for Claire Denis’s Nénette et Boni (1996), Trouble Every Day (2001), L’Intrus (2004), 35 rhums (2008) and White Material (2009). Hinchliffe wrote the score for Vendredi soir (2002). The synergy between their scores and Denis’s images and soundtracks (for the music is often incorporated with ambient, diegetic sounds) can hardly be defined in terms of the categories conventionally applied to the study of mainstream film music, where images and score are considered first and foremost in terms of the fulfilment of precise (narrative, expressive or affective) functions. This is not to say that, in Denis’s films, the music does not relate to specific elements of the diegesis – characters, setting and atmospheres are indeed shaped by the musical as well as the audiovisual compositions. Such relations, however, are embedded in the deeper, shared sense of musicality of soundtrack, images and music, emphasized by the recurrent overlap of diegetic and non-diegetic music.

In the case of Nénette et Boni, the band were introduced to the project as the film was already being shot, and a temp score provided for its editing. The soundtrack the Tindersticks offered was one of great simplicity – with a basis in Bossa Nova, much of the track hangs on binary rhythms and on alternations between a couple of chords. In its very hesitancy, the way it goes back and forth, suspends chords and merely sketches melodic lines into tiny leitmotivs, the music track does perfectly capture the universe of two unanchored youths, the liminal space between childhood and adulthood that they inhabit, and the diffidence of the character of the adolescent Nénette in particular.

In subsequent films – through the low, haunting bass tones of Trouble Every Day’s string orchestration or the floating sequences of bell-like chords of Vendredi soir – the score sets the dramatic tempo between a sense of spellbound suspension and sudden, irrepressible acceleration. Most crucially, however, the music effectively concurs with the images in giving a presence to the film’s most ubiquitous character: the city of Paris, appearing, respectively, in an unusual, gothic guise or as an enchanted space of potentialities. It is both the city as atmosphere that the music carries across, infusing the filmic space seamlessly and invisibly with an implicit, intangible diegetic presence, but also, as the score fuses with the soundtrack, the city as a profoundly sensual environment, one that appeals to multi-sensory perception – vision, hearing, smell, touch.

In turn, the opening credit sequence of 35 rhums offers a sketch portrait of Paris, both humorous and melancholy. Simultaneously evocative of the city and of cinema’s history, it takes the form of an auditory palimpsest, in which, a sense of location is ostensibly established yet at the same time challenged. The very beginning of the credits, featuring the elongated, floating sound of the ondes Martenot, of which the Tindersticks are fond, prefigures the first images – captured from the vantage point of the driving cabin of a suburban train, the opening sequence gives an impression of floating above the railway tracks. Such images are redolent with the memory of cinema’s beginnings, of the train rides that punctuate the city symphonies, bringing workers into the town centres. Yet, as the credit music proper starts, it brings forth something old-fashioned and very ‘French’, oddly reminiscent of the bal musette and of Tati’s Jour de Fête (1949).3 The ballad-like plaintiveness of the melodica, however, also evokes an elsewhere, a sense of exile that many of the film’s African French characters of the older generation implicitly share. Soon, an étude-like piano composition brings with it a more classical register, a different voice that weaves in and out of the existing melody. As the railway tracks unravel in front of us, crossing, merging and separating from other tracks, the music similarly talks of destiny, of encounters and losses, its slightly mournful tune concluding, unexpectedly, on the hopeful sound of a major chord.

Neither L’Intrus’s nor White Material’s music tracks offer such a hopeful pitch. What they have in common is a radical destructuring of the musical space. L’Intrus’s drifting guitar riffs are characteristic of a readiness to create a musical space that wilfully lacks a centre, eschewing a sense of narrative and conclusion that would undermine the films’ powerful evocation of post-colonial estrangement. Yet, as in the previous films, the scores in L’Intrus and in White Material emphasise the sensuous quality of the images – the sparse use of guitar, strings and percussion, bringing out hues, evoking colours, alternatively emphasizing a sense of depth of field or one of physical intimacy.

In the following interviews, both Stuart Staples and Dickon Hinchliffe describe their work with Claire Denis as a fluid, open process of co-creation – a remarkably open collaboration based on a common understanding of cinema and the search for the right ‘tone’. Ultimately, as Stuart Staples puts it, the aim is ‘to let the image sing’.

Conversations with Dickon Hinchliffe and Stuart Staples

Dickon Hinchliffe

Claire Denis is completely unique. Working with her profoundly alters the way one thinks about film music. She connects with music. She is not after conventional film scores – where music primarily emphasizes narrative and emotional development – she is after a tone.

‘A Form of the Blues’

Nénette et Boni was different from the other films. A temp score was used as the base for the film’s final score. We scored after the film was shot, but there is a sense that existing songs shaped part of the film. For the following films, Claire has been sending scripts, and we talk about them. We get to understand on a deep level what she is doing. It develops into a kind of conversation – a space where one is free to explore ideas. Claire Denis is interested in using instruments as well as non-instrumental sounds. There is a big contrast, in that way, between, say, Chocolat and Beau Travail.

I composed the score for Vendredi soir on my own and with a string orchestra while Claire was shooting. Claire Denis always thinks about music as she writes, however. For instance, she insisted that the music in Vendredi soir had to be in the air of Paris at night – as if coming through the windows of the houses and cars, spreading around. I therefore composed in a high register in piano and strings so that the music carries a lot of air, conveys a dreamy feel. In contrast, for Trouble Every Day, there was a powerful bass sound coming from the double bass and cello. As in all the records, Stuart [Staples] wrote the lyrics, and the song helped shape the rest of the film’s instrumental music.

I give demos while Claire is editing. It is quite a loose process – there is no crude way of fitting the visuals and the score. Most crucially, there is an avoidance of effects that end up telegraphing emotions as in Hollywood (no ‘sad’ and ‘happy’ music). Part of the score can relate to characters, but not in isolation. The music creates relationships between characters and between characters and their environment, in terms of intensities.

In Claire’s films, there is friction in music and sound. The score and sound-track create a third dimension. The music always emerges as a strong voice in the films – even more so because there is little dialogue. Dialogue is less important, and this opens up a poetic space in her films. So music and sound effects play a crucial role in affecting the audience. They become a more direct route to the unconscious than the visuals.

There is a flow in much of the scores rather than a rhythm or a beat: it evokes a state of suspension, or a liminal state. Suspended chords abound, creating a sense of the unresolved. Cues start and die in a non-conclusive way – it creates an impression of the unfinished.

Rather than melancholia there is intensity, a way of seeing the world, a form of the blues, as well as a lot of tenderness and humour. At the same time, Claire Denis films in a very physical, tactile way, both in terms of images and sounds. The way one hears things and sees colours – that is, what cinema should be about: a multiple engagement of the senses.

Stuart Staples

‘A Sense of Space’

What I do know is: we need a space in our music. We have always needed a sense of space to step into rather than be presented with something. Our music always asks you to step into it. And for this you need a sense of space. We don’t like to make things obvious or one-dimensional. It’s very unsatisfactory. It’s always better if you get a feeling of tension or ambiguity within the ideas. It’s not one thing you can step in. It’s the same with Claire’s cinema. It is so open; it makes you feel as a viewer, it never tells you how to feel.

One example, for me, is melody. Melody takes a lot of space. It takes a lot of mental space. I suppose in the film music I encounter, in the actual experience of it, it just takes up so much space. It leads you – I feel I am led in such a heavy-handed way. It seems the new trend is to pack every moment and every frequency. What people do generally leaves me cold. There are certain chords you use at certain moments – to leave people no choice but to feel this at that moment. With Claire, it’s more about a reaction and a connection, a conversation that has to do with music and images that allows a certain kind of a breath in the film and doesn’t try to choke it. Sonically, the grass bristling is as important as the music in the film. With Claire’s films, those kinds of details can be just as emotive.

The beauty of music is that there never has to be a reason for it. I cannot say that this particular piece of music is about this, or about that, but it is very much about a particular way of treating music in a film. I could not say exactly what that was, but it is very important to me that it be simple, with momentum and not to make any statement. You can hit something at a certain time, and it can just feel right. Like, you know, to do with a moment. It was very much true with the guitar in L’Intrus. There was no reason apart from something just chimed, and it was a starting point for that to chime, for both Claire and me. I believe the music in a film provides a different dimension to the experience.

It’s all about space and openness and ambiguity. Cinema, for me, is an experience of so many different senses, something that holds you for a certain period of time. You don’t really need to know what it has given you. You don’t really have to walk away with a checklist. If something just holds you there, you are enthralled by it – I think it is far more interesting. But there is kind of a pressure to make people feel what you want them to feel. Claire’s films are far away from that.

Working with Claire

Fundamentally, it’s about people, and whether it’s music or cinema, the media is secondary to the relationship between ourselves and Claire. So, it is just a creative relationship, the only one that we have, and that kind of bounces back and forth and allows things to change and happen and move. The thing about working with a group of people is, if I write a song, I have to make the people around me inspired about it. And if they get inspired, then I trust them, I trust their aesthetic. It’s kind of the same with Claire. The first thing she has to do is fascinate and enchant us and inspire us to make something. It’s not a given. To us, it’s not a job. Hopefully, at the end we make some money and carry on, but so far we’ve tried to never ‘have a job’. To never have to do this because of the money. It’s not a job, and you can’t treat it as a job. We look at what inspires us. Where will this take us to, which adventure?

That’s the kind of thing I feel when people ask, ‘Do you want to make music for other films?’ And I think about it. I imagine what the process is – you know, without that trust and conversation, I always shy away from it because it’s a special thing. It has so much to do with the way Claire works generally, whether it is with her cinematographer, or her editor, or with her actors. She always forms relationships where people have space to bring a part of themselves and surprise her, and she opens her mind and thinks about it. But, at the same time, she is able to do that because she is so strong, so confident inside about what she wants. So she is able to allow people to move, she is not holding on to things (‘It has to be like this, it has to be like that’). She wants to get her head around other people’s perceptions, understand how people view these things. At the same time, she is immovable, you know – I mean, for the central vision of where she is going. I think that it is a great, rare kind of thing and makes her films unique.

Finding an Entry Point

Every film we have done with Claire, we have had a different approach. It’s not been a standard way of ‘we now do this and now we do that’. It’s always about finding a starting point to enter the film. With our first film score, with Nénette et Boni, it was kind of ready-made because Claire was so influenced by our second album, especially the song ‘My Sister’, that it kind of presented us with this kind of thing to grow from, something that was already inside the film – like the song and the song title were already inside the film and we had to build around that, and that was great because it was our first film, and it gave us a starting point.

With Trouble Every Day, the starting point, for us, was about the romance, connect...

Table of contents

- About the Author

- Bookreview

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Foreword: ‘Klärchen’

- Part I Interviews

- Part II Relations

- Part III Global Citizenship

- Part IV Within Film

- Bibliography