![]()

Part I: Within Modernism

![]()

2 Form (& Matter)

Now on the face of it nothing seems more ridiculous than undoing a building. Quite the contrary. Undoing is a terribly significant approach for advancing architectural thought in this point in time. Everybody, to some extent, accepts architecture as something to look at, to experience as a static object. Few individuals think about or bother visualising how to work away from it, to make architecture into something other than a static object.

—Gordon Matta-Clark1

Matta-Clark was broadly critical of the role that ‘form’ assumed within modernism, how it contributed to the acceptance of architecture as static object. However, as we have seen, he did not consider formal work to be exclusively reductive, nor did he perceive the term ‘formal’ as merely pejorative:

Things die as they become formal…That’s reverse obtuse thinking, so let me reference that: when a thing does not have any life at all, it seems to be have a lot of manipulation for manipulations sake. And I suppose that’s the way I interprete the word “formalism”. At the same time I do recognise that certain kinds of activity can be essentially formal without being rigid or mortuistic.’ 2

When Matta-Clark spoke out against formalism, he targeted the ‘manipulation for manipulation’s sake’ that he witnessed in (North American) high modernism, although the response that can be read through his projects was oblique. Form returns there after pursuing something of a detour, and when it returns it does so in a mode that is different from that of modernism.

Matta-Clark’s concerns were that modernism’s licence to manipulate form came at a price it was not prepared to acknowledge, and that the authority it claimed for this licence was established by a sleight of hand. Both these issues emerged as a result of modernism’s general drive for disciplinary purity, which in the case of painting or architecture involved form’s being linked to a quality of surface. More particularly, pure form referred not simply to outward shape, but to an ideal surface that was distinct from the material or ‘literal’ surface of a thing. This apparently straightforward situation not only denied other contemporaneous modernisms, it also concealed one of the most long-running and contentious debates within Western philosophy, aesthetics, art and architecture concerning the role of form. In particular here, this involved its relationship with ideas, on the one hand, and with matter, on the other: it concerned, in other words, the relationship between design and realisation.

For influential art-critics such as Clement Greenberg, or his follower Michael Fried, bad art (‘non-art’) was marked by its inability to attain pure surface form, due to the intrusion of other aspects of a thing that would reveal its broader involvement in a network of unsanctioned relationships.3 Similarly, modern architecture’s preoccupation with pure surface form motivated attempts to launder form of any concerns or relationships that prevented it from occurring on its own terms. The 1932 International Style exhibition’s covert rejection of any socio-political agenda in favour of a definition of architecture as (preferably regular) volume echoed Le Corbusier’s famous assertion that architecture was nothing but the play of volumes in light. Rowe’s architectural Contextualism, which provoked such strong criticism from Matta-Clark, was also explicitly idealist and shared a taste for surface formalism.

For Matta-Clark, the aim of attaining purity of superficial form was hugely reductive: although there were instances of painting that had implicitly attacked this aspect of modernism by penetrating the surface, he remarked that the same could not be said of architecture.4 This situation led him to produce an extensive series of works that were in part an investigation of surface formalism.

Surface Formalism

THE NEW YORK DEPT OF HEALTHS DEFINITION OF SUITABLE

SURFACES

IMPERMEABLE AND WASHABLE

—Gordon Matta-Clark5

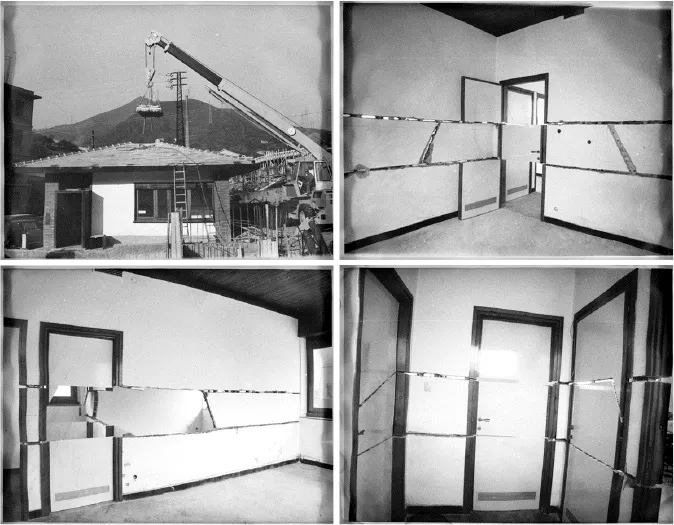

Matta-Clark was suspicious in equal measure of both impermeable surfaces and the institutions that deemed them suitable. His project Circus, discussed in the previous chapter in terms of ‘new kind of space’ that he sought through his method of discrete violation, also demonstrated an equally strong interest regarding the process of cutting into the material of the building itself. This was the last of many realised cuts, which had begun modestly with projects such as the Santiago project. This, together with other early cuts such as the series Bronx Floors illustrated in figure 3, sought to introduce new experiences of space by opening up unexpected views through a building. Reflecting on the emergence of his cutting projects in an interview with Liza Bear, Matta-Clark stated that alongside these new views, he was perhaps more interested in the consequences of the cut upon the material—and particularly the surface of that material—itself.

At that point [around 1973] I was thinking about surface as something which is too easily accepted as a limit. And I was also becoming very interested in how breaking through the surface creates repercussions in terms of what else is imposed by a cut. That’s a very simple idea, and it comes out of some line drawings that I’d been doing… [I]t was the kind of the thin edge of what was being seen that interested me as much, if not more than, the views that were being created… the layering, the strata, the different things that are being severed. Revealing how a uniform surface is established.6

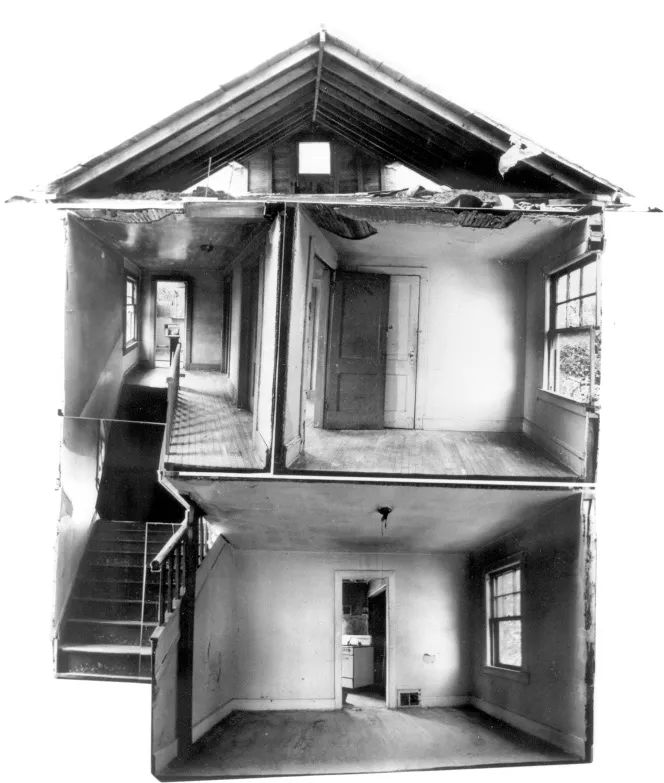

He made very similar remarks to Donald Wall, though dwelt a little more on the establishment of surface: ‘…what interests me more than the unexpected views that were being generated by removals is the element of stratification. Not the surface, but the thin edge, the severed surface which reveals the autobiographical process of its making.’7 This ‘autobiography’ and the spatial complexity were both products of the cutting operations, and clearly they were closely inter-dependent. Moreover, they both contested the ‘static object’ conception of architectural form that Matta-Clark criticised, working away from the cut surface in two different directions. The spatial experience of these projects could not be anticipated from any of the ‘ideal’ forms of which they were comprised; it had to be a three-dimensional, dynamic experience, one that occurred over time and continued to offer ‘unexpected views’. Additionally, the revelation of what was usually hidden away behind the surfaces of walls, floors and ceilings displayed the process of making, its maintenance and decay, in short the process of change, that the built ‘object’ was caught up in.

As Matta-Clark stated in the context of Circus, the discrete violation of a visitor’s sense of space presumed that aspects of the previous situation would comfortably survive the cutting operation and remain a crucial ingredient in the new experience. The same cannot quite be said of the cut surface (where what was revealed did not belong to the same mode of experience presumed by the surface itself), and we might at this point ask whether, and if so how, Matta-Clark’s projects usher in a clearly new sense of form.

3 Bronx Floors: Threshole, 1972 (previous page), A W-Hole House: Roof Top Atrium, 1973 (above), and Splitting, 1974 (following pages)

Splitting, A W-Hole House, and other work such as Bingo, 1974, operate by deploying standard techniques of architectural design, in particular orthographic drawing conventions, out of the usual sequence, out of the protected domain of the architect and onto the building proper. Although he made cuts to buildings from as early as 1971, such as the Santiago piece illustrated in figure 2, or the renovations he made as part of the collaborative Food Restaurant in New York (1971–3), the more deliberate investigations into the repercussions of cutting began around 1972 with a series of cut drawings, and work to buildings such as the Bronx Floors series. The scale of this work increased substantially in the following two years with A W-Hole House, Splitting and Bingo. Matta-Clark made four cut drawings for the exhibition of Intraform and A W-Hole House: Datum Cut at Galleriaforma in Genoa, 1973, underscoring the point that his cut drawings were not simply a precursor to a building dissection.

Matta-Clark’s cutting illustrates his broad concern to address form and architectural object together; as a technique, it cut against not only the surface formalism of his Cornell education, nor modernism’s close liaison with form, but with a far longer architectural tradition that sought to separate architectural form from built object. Although the white walls that characterise, even caricature, modern architecture mark the apogee of this separation by appearing to deny any kind of material involvement in architecture, this really just marks the culmination of a process that emerged during the Renaissance, when architecture sought to separate itself from the manual trades of construction. Moreover, the idealised approach to architectural form that emerged to justify that separation was itself linked back to a much older difficulty concerning form that can be traced back within the Western tradition to pre-Socratic thought, though which is perhaps epitomised by Plato’s Theory of Forms.

According to Plato’s theory, forms were located in an ideal, metaphysical realm. Things in the world were imperfect imitations of these unchanging ideal forms; although the imperfect form of worldly things was available to the human bodily senses via their outward shape, the ideal form they referred to could only be approached by the intellect. Plato used the word eidos (ειδος) for both these situations, form-as-shape apprehended by the senses, and form-idea comprehended by the intellect. For Plato, how one proceeded beyond the surface of a thing and negotiated this complex relationship between surface form-shape and form-idea was crucial. He was adamant that truth would only give itself up to objective enquiry. To get below the superficial appearance of things required that they be divided up in a way that was informed by and respected the component forms that together made up each thing: ‘…we are enabled to divide into forms, following the objective articulation; we are not to attempt to hack off parts like a clumsy butcher…’8

Sidestepping the broader applications that Plato sought for this method, there are two aspects of it that are important in the present context. Firstly, the method of division itself needed to be ‘scientific’ or ‘objective’: secondly, the same method provided Plato with the model he recommended for ‘skilful’ or ‘scientific practitioners’ of artistic production. For example: ‘Whenever… the maker of anything keeps his eye on the eternally unchanging and uses it as his pattern for the form and function of his product the result must be good…’9 Now while this echoes Schumacher’s account of Cornell Contextualism given in the introduction, Matta-Clark’s technique clearly looked the other way, and got below the surface of form thanks to some very deliberate and clumsy butchery, and thus called the underlying assumptions and priority given to form-idea into question.

While his work was not anti-intellectual, it did operate by reintroducing, or re-evaluating, the balancing role played by form-as-shape, with all the material, worldly implications this brought. For example, Circus, which was generated by the inscription of three spheres (the most perfect of all the Platonic solids) into the existing rectilinear geometry of a Chicago townhouse, did not prevent either of these geometric forms being perceived. However, as figure 1 demonstrates, what the cutting did bring about was a disruption in the usual legibility of surface form, the ease with which surface form could be perceived, and thus a disruption in the unquestioned assumption that experience should proceed from perceived experience of clear surface form to clear understanding that is linked somehow to an unchanging truth. In this example, the disruption is not caused by a contest between two strong geometric formal systems, but by the role of surface form being disrupted by the mutual interference between architectural form and cut surface. This was not just an interplay between positive and negative spaces or forms, but between architecture as static object, and architecture as a dynamic, contingent process. To reiterate the broader claims made earlier for Matta-Clark’s notion of discrete violation, this operated by setting up a process of creative questioning, rather than with the intention of providing a clear answer.

Eidos, disegno, and Formal Clarity

The consequence, at least on the idealist account of form in either its traditional or modernist guises, of Matta-Clark’s shifting ‘objective’ formal analyses out of the realm of the intellect by bringing them to bear so tangibly on things is that the forms attained through such operations would allegedly lose their intellectual clarity. That is to say, there is a possibility that Matta-Clark’s cuts would prevent ‘form’ from escaping the mundane world of surface, and that they would remain incomprehensible. For Plato, this approach would be a turn away from unchanging, universal truth, though Matta-Clark was clearly aware of this and attentive to the repercussions of cutting in this way.

Indeed, several of his other cutting projects, such as those illustrated in figure 3, literally enacted objective, intellectual approaches to dividing the form-shape of wh...