![]()

1

Steps to the Throne

Every one complains of Bonaparte; every one talks of the Court.

Diary of Bertie Greathead, Paris, 1 January 1803.

On 19 February 1800 a procession of carriages drove through the streets of Paris to the Tuileries palace. The carriages contained councillors of state, ministers and, in the grandest carriage of all, drawn by six white horses presented by the Holy Roman Emperor, the three Consuls of the French Republic. The procession drove past a barrier surmounted by an inscription saying ‘Royalty has been abolished in France, it will never return’ and into the courtyard of the Tuileries. The First Consul, General Bonaparte, then held a review of the Guard of the Consuls. That night he slept in the Tuileries. It was to be his official residence, and the seat of his court, for the next fourteen years.1

The Tuileries, begun in the sixteenth century, and enlarged and redecorated under Louis XIV, was a long grey building, which stretched between what are now the two westward-protruding wings of the Louvre. Louis XVI had lived there, half king, half prisoner, at the beginning of the French Revolution, from 1789 to 1792. Its walls were still scarred with bullet and cannon marks from the uprising on 10 August 1792 which had resulted in his overthrow and the establishment of the first French Republic. Siéyès, an ex-priest turned revolutionary politician, reminded Bonaparte of the Tuileries’ unhappy memories of the fall of Louis XVI a few days after his move to the palace. The First Consul’s fierce reply revealed his determination to stay in power: ‘If I had been Louis XVI, I would still be Louis XVI, and if I had been a priest, I would still be one.’ As Siéyès realized, sooner than most people, France now had a master; and in the next four years its master acquired a court.

It was Siéyès who had helped Bonaparte to become First Consul. Bonaparte, although only thirty-one, was the most celebrated general in the French army. Born in 1769, the son of a Corsican noble, he had been educated at military schools in France under Louis XVI – where he was disgusted by the disdain that pupils from older and grander noble families showed for those less well-born than themselves. After he left school he was bored by the prospect of service in a peacetime army: he became so discontented that by 1789 he felt republican as well as anti-French.

Although Napoleon had benefited from the old regime which had existed before 1789, like many nobles he found new opportunities under the Revolution. He supported every stage, including the overthrow of the monarchy and the Reign of Terror. Robespierre’s brother Augustin called him ‘an artillery officer of transcendent merit’. Bonaparte helped suppress revolts by royalist enemies of the Republic at Toulon in 1793 and Paris in 1795 (when they tried to storm the Tuileries).

After 1795 France was ruled by a new, less blood-thirsty government called the Directory, headed by five Directors. They sent General Bonaparte to command the French armies fighting Austria in Italy. He rapidly showed himself to be a brilliant, self-confident, ambitious and above all consistently victorious general. His sense of publicity was almost as extraordinary as his military genius. He subsidized newspapers in France, with titles like Journal de Bonaparte et des Hommes Vertueux, which helped publicize his victories.2

By 1798 he was so popular that he was an embarrassment. The Directory, which was temporarily at peace in Europe, sent its most successful general to invade Egypt. It was hoped to threaten England’s trade with India; and Bonaparte was happy to remove himself from contact with an increasingly corrupt and unpopular regime. After a dazzling year of conquests in Egypt, his army was checked by British and Ottoman forces at the siege of Acre in Syria. He returned to France in October 1799, a sun-tanned young conqueror. He did not have any orders: but the government of the Republic had by then lost the respect of the majority of the French nation.

The Republic was at war again, with Britain, Russia and Austria. The economy and much of the countryside were in chaos: some of Bonaparte’s own servants were robbed by bandits on the way back to Paris. Royalists and left-wing politicians were working for the overthrow of the corrupt ex-revolutionary politicians, headed by the five Directors, who had ruled France since 1795. The government had no committed supporters. Everyone was discontented, even the Directors themselves, of whom Siéyès was one.

Nevertheless, there was a constitution with two parliamentary chambers, the Councils of Ancients and of the Five Hundred, which still inspired a certain respect. So the coup which Siéyès prepared with Bonaparte and Talleyrand (the brilliant, corrupt politician who was already a legend for spotting the winning side) needed to preserve a facade of legality. At first everything went as planned. On 9 November a member of the Council of Ancients declared the country in danger: the chambers should move from Paris to Saint-Cloud, six miles outside. The leading Director, Barras, resigned on the advice of Talleyrand. The next day, in Saint-Cloud, which was packed with troops, the Council of Ancients began to turn against Bonaparte after he had made a disastrous speech denouncing the government: his strong Italian accent did not help. The Ancients, who were wearing their uniforms of red togas, began to shout ‘Outlaw him! Outlaw him!’ But General Murat entered at the head of the Guard of the Legislative Body crying: ‘Grenadiers, forward! Expel them all!’3 The deputies fled through the park of Saint-Cloud, shedding their togas as they went.

The chambers were dissolved. Bonaparte became First Consul under a new constitution, which he drew up with the help of Siéyès: two able and obedient politicians, Cambacérès and Lebrun, became Second and Third Consuls respectively. Siéyès, a weak and expendable personality, was paid off with part of the money left behind in the Directors’ account. The legislature under the Consuls was composed of a nominated Senate, an elected Tribunate and a Legislative Body, sitting in Paris in three former royal palaces. Parisians paid little attention to the new constitution, the fourth in ten years. A Prussian diplomat reported that the population was blasé about everything except peace.

Indeed, by 1800, despite the confident inscription above the entrance to the Tuileries, France was ready for a return to monarchy. The Revolution had killed thousands of people, caused many more to emigrate, and precipitated catastrophic wars and inflation. For most Frenchmen by 1800, the events of the Revolution were a powerful argument against a republican form of government. Bonaparte and his ministers were careful, at first, to maintain an appearance of commitment to the republic. Nevertheless, they told foreign ambassadors that they were convinced that ‘monarchical government is the only one suitable to large associations of men’. If it had been overthrown in France, the fault was ‘the weakness of the ruling family’.

The real strength of the republic lay in the fact that the abolition of feudal dues and the sale of the property of the Church and émigrés had resulted in a massive redistribution of wealth which had benefited many Frenchmen, particularly the richest peasants and bourgeois. After ten years of continuous upheaval, France wanted a rest from revolution, at the same time as confirmation of its material gains. For most Frenchmen after 1800 Bonaparte seemed the best guarantee of both. An official proclamation had described the new Constitution as based on ‘the sacred rights of property, equality and liberty’.4 The sequence of words was both significant and reassuring.

The return of a court to France seemed almost as natural as a return to monarchy. A splendid court was as necessary to France as a well-drilled army to Prussia or a powerful navy to Britain. The Bourbon kings’ glorious court at Versailles had had an immense impact on the manners and customs, the social structure and the economic and artistic development of France. Frenchmen had been proud that it was the grandest court in Europe. Many of the officials and servants of the old court were still living in and around Paris after the Revolution (which many of them had supported), as were the employees of the luxury trades – making china, silver, embroidery, tapestry and furniture – which the court had encouraged.

A former First Woman of the Bedchamber of Queen Marie-Antoinette was running the smartest girls’ school in France, the Institution Nationale de Saint-Germain, outside Paris. Among its pupils were the First Consul’s youngest sister Caroline Bonaparte and his wife’s daughter by her first marriage, Hortense de Beauharnais (a particularly quick learner). The school also included members of the new rich and the old nobility, such as Agläé Auguié and Félicité de Faudoas, who were to marry two of the First Consul’s most famous generals, Ney and Savary.

Through her school Madame Campan, clever, worldly and moralizing, provided one of the many links between the old and the new regimes. They were not two separate worlds: one was simply a redefinition of the other. Indeed in the future Madame Campan would help former servants of the Queen and the King’s aunts to obtain jobs in the households of Madame Bonaparte and her daughter; and she would be used as a mine of information about the habits and etiquette of the court of Versailles.

Another figure from the past who frequently entertained under the Consulate was Madame de Montesson, the morganatic widow of a Bourbon prince, the Duke d’Orléans. Among her guests were members of the old nobility and the new élite, and artists and architects of the old regime in search of commissions under the new. Men first started to wear silk stockings and buckled shoes again in her house, after ten years of boots and trousers under the Revolution. She gave a splendid reception in 1802 in honour of the wedding of Hortense de Beauharnais to a younger brother of the First Consul, Louis Bonaparte. The 800 guests admired the valets wearing full livery and powdered hair, and the Duchess d’Abrantès (then Madame Junot, wife of a general of the Republic) remembered it as ‘a model of what happened later’.5

Clearly the new world which had arisen from the Revolution, as well as the world of the old regime, was ready for a court. The masters of the Republic were proud of their newly acquired wealth, and their brilliant careers in the army or the administration, and needed somewhere to display themselves. A police report of 1802 suggests the attitude of the new élite to their revolutionary past. General Lefebvre, a republican officer who had risen through the ranks, was infuriated by a worker’s complaints about the price of bread. Lefebvre said that they were no longer living in the days of Louis XVI or the Convention, and that the rabble should no longer think that they were the only people worth worrying about.6 Like the pigs at the end of Animal Farm, the new rulers of France were beginning to seem no different from the old.

The government as well as the élite wanted a court. Visual splendour, one of the basic components of a court, was as necessary for a government in 1800 as a good television image is for a politician today: in 1795 even the government of the Republic had shown that it felt a need for splendour by creating garish costumes for its officials and holding regular receptions at which they could be displayed. Most members of the élite of power and wealth, whether royalist or republican, would have agreed with Bonaparte’s mother when she wrote to her son: ‘You know how much external splendour adds to that of rank or even of personal qualities in the eyes of public opinion.’7

A court is the magical result of a combination of power, visual splendour, outward deference and a personal household staffed by members of the élite. Bonaparte had power thanks to his coup d’état, and his power was, in appearance, legitimized by the plebiscite of January 1800, which approved the new constitution by 3 million votes. It has only recently been discovered that in fact Bonaparte’s brother Lucien, the Minister of the Interior, simply added 1.5 million affirmative votes to the real, far from unanimous result of 1.5 million (out of an electorate of about 7.5 million voters).

After Bonaparte moved to the Tuileries he had the second element of a court, visual splendour. Although scarred by revolution, the Tuileries was a royal palace and, like most royal palaces, radiated an atmosphere of hierarchy and deference. As the horrified liberal writer, Madame de Staël, wrote after Bonaparte’s move: ‘it was enough, so to speak, to let the walls do the work.’8

Bonaparte was keen to help the walls. His architect Fontaine wrote in October 1801 of his interest in the decoration of the Tuileries, and of his insistence on ‘the magnificence due to his rank’. Very soon his apartments were furnished with ‘eastern magnificence’ in yellow and lilac-blue silk, with white and gold fringes. There were old masters on the walls, Sèvres vases mounted in ormolu on the tables and his wife used Queen Marie-Antoinette’s jewel-cabinet. In 1802 Mary Berry wrote: ‘I have formerly seen Versailles, and I have seen the Little Trianon, and I have seen many palaces in other countries, but I never saw anything surpassing the magnificence of this.’ In the next few years, as Fontaine records with delight in his diary, the Tuileries and its surrounding area were cleaned up. Unsuitable houses and inscriptions were removed; people not directly connected to the personal service of the First Consul were expelled. The whole quarter was beginning to resemble a royal palace and its precincts.

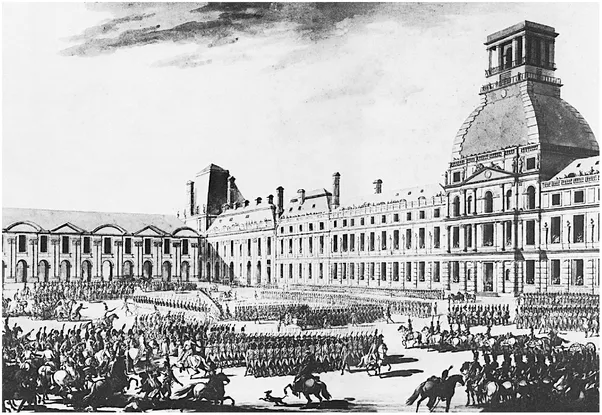

1. Swébach-Desfontaines, Review by the First Consul at the Tuileries

Everyone wanted to watch this dazzling military ceremony: the windows of the Tuileries are packed. Bonaparte is to the left, on a white horse which had belonged to King Louis XVI After a few months Bonaparte also began to be surrounded by the outward forms of ceremony and deference. Every ten or twenty days, after a review of his awe-inspiring guard, he held a reception for senior officers and officials which provided a startling visual display of his position at the head of the French Republic.9

In the state apartments on the first floor of the Tuileries, overlooking the courtyard where the guard was reviewed, access to the First Consul was determined strictly by official rank. Captains were admitted into the first antechamber preceding the First Consul’s official reception room, senior officers into the second, generals into the third and councillors of state and ambassadors into the fourth. Bonaparte’s receptions were a vehicle through which senior officials and officers of the Republic could satisfy their longing for recognition of their own importance. They were also a convenient meeting-place and centre of news. Above all, the hierarchy of antechambers, as well as the presence of his guard in the courtyard below, were a visible sign of the power and authority of the First Consul. Officials and officers were linked in a chain of authority which culminated in him.

The English visitors who inundated Paris after the return of peace in 1801 were delighted by such signs of a return to normality and monarchy in France. ‘None of the levées of the European courts can vie in splendour with those of the Chief Consul,’ wrote one English visitor in 1801, and many other foreigners were equally impressed. Strict etiquette and military might, always the most remarkable features of the Napoleonic court, were there from the start.

In September 1801 the Prussian Ambassador wrote that ‘the household of the First Consul is increasingly taking on the appearance of a court’.10 The last element of a court, household officials from the élite of power and wealth, now appeared at the Tuileries: in November, two sons of pre-1789 financiers, Didelot and de Luçay, were appointed Prefects of the Palace, and Bonaparte’s most intimate friend and confidant Duroc became Governor of the Tuileries.

In March 1802 ladies began to be presented formally to Madame Bonaparte. An Irish visitor noted that ‘The etiquette of a Court and Court dress are strictly observed’ at the First Consul’s audiences. Indeed, life in the palace was now so formal and so respectable that a former actress, the wife of Bonaparte’s great admirer Charles James Fox, could not dine at the Tuileries, as she had not been presented at St James’s.

The First Consul was at the height of his popularity. His government had startling achievements to its credit. The institution of Prefects by a law of 17 February 1800 gave the central government a permanent executive agent in each department, for the first time since 1789. The new Prefects, recruited mainly from former members of revolutionary assemblies, could correspond directly with Paris by telegraph. They soon established themselves as the masters of their departments, and helped to provide France with the strong government for which it yearned. The budget was balanced for the first time in a decade in 1802. The government could now pay holders of government stocks in gold, instead of in discredited paper currency. A new law code was issued in 1804. In clear, concise French it ensured equality before the law, the right to civil marriage and divorce, the equal division of 75 per cent of a testator’s property among his children, and the abolition of all forms of legal privilege. It was essentially the work of professional jurists, and was the culmination of years of preparation, begun under the old regime. Nevertheless Napoleon presided at 36 of the 84 sessions of the Council of State devoted to the Code, and it was renamed the Code Napoléon in 1807. It was more modern and ef...