![]()

CHAPTER 1

READING IN DETAIL: ADAM AND EVE IN CLOSE-UP

[I]t is idle to revive old myths if we are unable to celebrate them and use them to constitute a social system, a temporal system […] Let us imagine that it is possible.

– Luce Irigaray, Sexes and Genealogies, 81

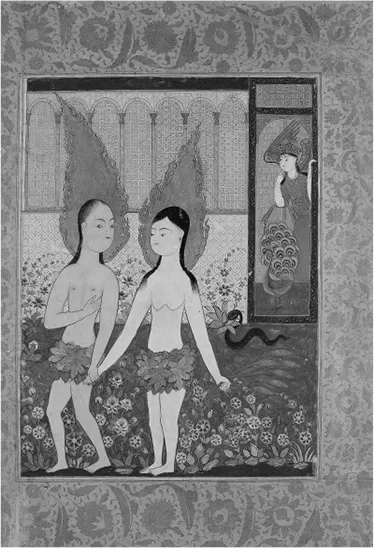

Let us set off with where it all supposedly started. Let's start with a myth. Have a look at a seventeenth-century miniature depicting male and female figures, wearing nothing more than tree leaves covering their genitals, placed slightly to the left of the picture plane (Figure 1.1). They both have colossal flames surrounding their heads. The woman carries a sheaf of wheat in one hand and holds the man's hand with the other. Their faces are turned toward each other though their gazes do not meet. She has downcast eyes, whereas he has a hesitant look, as if he is torn between wanting to look at the woman and the viewer.

The couple stands on the edge of a garden with oversized flowers. Behind the woman there is a snake crawling behind a bunch of leaves. At the rear back, we see the exterior walls of an edifice decorated with a web of ornamentation assuming hexagonal and other geometrical patterns. Its arches of violet marble are supported by red columns. The viewer gets a glimpse through the arches of the interior walls of the building. To the right of the arches, a figure with colourful wings wears a red outfit and is adorned with a golden crown. S/he holds on to the doorframe with one hand and with the other raises her/his forefinger towards her/his face, a gesture connoting surprise. In front of the figure there is a blue peacock with a flamboyant tail.

Figure 1.1 Expulsion of Adam and Eve, Falname, artist unknown, 1614–16, Topkapi Palace Museum (H. 1703, f. 7b), 47.5 × 34.5 cm.

The viewer who is familiar with the story will recognize the scene as that of the Fall. The naked male and female bodies whose genitals are covered with tree leaves call to mind the story of Adam and Eve. The flames floating around the heads of the figures are enough of a motive to make it understood that the figures are not ordinary human beings but rather have something unearthly about them. Upon recognizing the details, the viewer can comfortably expand the angle of her look toward the background setting, which, without further examination, could be named the Garden of Eden: the figures' nakedness and the tree leaves refer to the time in the story when the couple are still in paradise. The figure at the doorstep who looks completely human can be distinguished from the couple because of the exaggerated costume and colourful wings. These features would enable the viewer to identify the figure as an angel. The peacock, with his beautiful tail, is heavenly enough to make the viewer complete the scene just before her eyes alight on the serpent, the creature that actually concludes the whole story. Now, the viewer knows that she is looking at Adam and Eve and can conclude – because of the tree leaves – that they have already committed the primordial sin. And then, having this knowledge, she expects that the inevitable expulsion is taking place. At this point, the positioning of the couple to the left within the composition of the image gains an additional meaning since it enables the viewer to understand that they are turning their back to the other elements – the architectural setting, the angel, the peacock, and the serpent – and are facing toward the outside of the picture plane: the Garden of Eden.

As is well known, the myth of the Fall has been articulated in the books of the Abrahamic religions. The story of Adam and Eve is told in the Book of Genesis in chapters 2 and 3, with some additional elements being given in chapters 4 and 5. In the Qur'an the story is evoked in fragments in different surahs: al-Baqara (2: 30–9), al-Araf (7: 11–25), al-Hijr (15: 26–44), al-Isra (17: 61–5), Ta-Ha (20: 115–24), and Sad (38: 71–85).1 Even though the two versions of the story in the Book of Genesis and the Qur'an maintain a similar fabula, the narratives differ considerably in detail. The introductory reading of the miniature as “The Fall” is based on the viewer's ability to recognize the figures and pictorial details in a synecdochal relation to an external, canonical text. The viewer does not have to refer to the text directly, that is, she does not have to have read the text, say, in Genesis or the related verses in the Qur'an. She only has to know the codes to be able to recognize a particular detail in reference to the pre-text so as to make up a culturally adequate reading of an image. Once the visual marks have been found, such as those of Adam's and Eve's nakedness and the tree leaves, and have been interpreted in relation to the pre-text, the pre-text takes over the image, thereby simplifying the reading process and allowing the viewer to read the other details in relation to that particular text.

This is the founding tenet of iconographic analysis, which facilitates the viewer to identify certain pictorial elements, as distinct cultural motifs by referring to the themes and concepts transmitted through pre-existing sources. Such an informed reading, which relies on the principle of recognition, prevents the viewer from reading the image “by herself” and enables her to make a “correct” assessment of the elements.

In her Reading “Rembrandt”: Beyond the Word/Image Opposition (1991), Mieke Bal advances a model for reading in detail that complements iconographic analysis. Narrative reading starts by examining a detail that the iconographic methodology, because it continually reads the visual in relation to the verbal by concentrating on the correspondence between the “written” pre-text and the image, cannot account for. Narrative reading, on the other hand, starts where iconographic analysis stops short and reads into the image to seek out the narrative structure. It concentrates on the ways in which visual elements tell a story. In such analysis, the notion of the detail gains prominence.

Inspired by Bal's theoretical framework and Naomi Schor's and Roland Barthes's takes on the status and the operation of the detail, this chapter dwells on the narrative function of the pictorial detail in our reading of images. In this way, it not only advances the inquiry on the relationship between words and images hinted at in the introduction but also sketches out the methodological stance throughout this study. The analysis of “The Fall” miniature privileges pictorial details that may not fit into a certain reading of images performed within the paradigm of recognition on the basis of texts. As I will argue, this incongruity paves the way for a productive encounter between the viewer and the miniature because it invites the viewer to create her own story of the image, which may be in opposition to the story dictated by the pre-texts.

Making Up Stories: In and Out of the Image

“The Fall” miniature painting is taken from the Falname (The Book of Divination), written in Turkish for Sultan Ahmed I (r.1603–17).2 It belongs to the literary genre known as Falname/Falnama that was widely produced within Islamic cultures. It includes “prayers, descriptions of the shrines of saints which were considered to have healing properties, miraculous events, and so forth” (Brosh and Milstein, 1991: 25). Conventionally, the falnames deal with the lives of Qur'anic prophets and characters, as well as mythological creatures and their miracles. The stories include Abraham about to sacrifice his son Ishmael, Abraham cast into fire by Nimrod, Jonah and the fish, and Noah's ark and the deluge.

Although an exact date of the book cannot be given, in the preface the vizier and artist Kalender Pasha states that he compiled this album as an offering to Sultan Ahmed I. It is known that Kalender became a vizier in 1023/1614 and served in this capacity for two years before he died. Since he refers to himself as a vizier in the preface, the compilation of the manuscript can be dated to these two years (1023–5/1614–16) (Bağcı, 2008: 262). It contains 35 miniatures painted by many different artists (Atasoy and Çağman, 1974: 65). The style of the Falname miniatures, compared to that of the miniatures of previous Ottoman painting schools, show different features. In general, miniatures of Falname are fairly large in size for those of the Ottoman period.3 They are also painted with thick brush-strokes using a comparatively wider colour scheme. Moreover, compared to the manuscripts of the period, with their tiny elegant figures, these miniatures contain fewer large-size figures.

Even though the Falname contains no reference to the artist or artists who created the miniatures, Metin And hints at the possibility that its miniatures were made by artists from the Esnaf-i Falciyan-i Musavver (Guild of Image-readers).4 This type of painter was mentioned by Evliya Çelebi, a famous seventeenth-century traveller, in his book Seyahatname, in the part where he gives a detailed account of the miniaturists in Istanbul.5 Evliya Çelebi mentions one such seventeenth-century image-reader, namely Hoca Mehemmed Çelebi, who owned a workshop in Istanbul where he performed fortune-telling for the customers. At his shop, he displayed miniatures mounted on large-size papers that had been created by the much-admired masters of the past. His clients would give him a silver coin (akçe) and select at random one of the displayed images. Consulting these images, which might depict scenes from different love stories or show the enmity and wars among the kings of the past, he would “recite his own metrical and rhyming verses” (Bağcı, 2008: 238).

As Bağcı notes, no record survives of what Hoca Mehemmed's paintings were like, but in all likelihood they were related to a visual tradition of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Falnames, such as the one in question (238). The paintings of the Falname and the relevant texts for divination were juxtaposed in such a way that each miniature, placed on the verso of a folio, and the corresponding text, placed on the recto of the following one, completed each other.6 The texts gave short information concerning the fortune of the person who had spontaneously opened the pages of the Falname. They were supplemented with two couplets in verse.

As Banu Mahir has proposed, because of their large size the Falname miniatures could have been used for pictorial recitation (2005: 70). In fact, in his preface to the Falname, Kalender Pasha states that the book can be used for divination: a randomly chosen illustrated page would be interpreted as giving an indication of one's future.7 Accordingly, Bağcı argues that the miniatures of the Falname must have been executed as facsimiles, as each miniature carries vertical or horizontal folds showing that they “must have been folded over and kept as loose leaves for quite a long time, before being bound as a codex” (2008: 239). She adds that the miniatures might have been folded so that they could not easily be seen by the fortune-seeker so as to leave the selection to the divinely ordained fortune of the person.8 In this respect, she suggests that the Falname manuscript brings two traditions together, “that of loose-leaf paintings used as devices for recitation, and that of the illustrated manuscript”: hence juxtaposed here is a practice of urban popular culture with the practice of producing precious manuscripts for courtly circles (240).

In the preface, Kalender Pasha gives us further clues about the album he prepared. He states that he “has collected, arranged and ornamented the illustrated, gilded, and calligraphically penned pages and plates, and submitted them as a gift to his imperial presence” (262). He adds that he wishes that the sultan's niyets (wishes) will come true. According to Bağcı, unlike several other divinatory treatises, Kalendar's Falname does not require an intermediary person to interpret its omens. “It adopts a ‘teach yourself’ approach, by informing the reader of necessary techniques and providing relevant texts, thus facilitating the use of the paintings by any reader.” (263)9

The proposed divinatory function of the Falname leaves us with a complex cultural product that works at different levels. The book includes written text and visual illustrations that are orally interpreted by a potential reader/viewer. In this respect, the Falname operates simultaneously on textual, visual, and oral levels; it requires a reader of the text, a viewer of the image, and a storyteller who performs a tale. What interests me in the proposed act of self-fortune-telling is the perfomativity of the story-teller.

The stories illustrated in the Falname, such as the expulsion from paradise, are based on religious texts. They are transmitted by textual, visual, or oral means and have become embedded in cultural memory. Although their cultural significance varies from culture to culture (and in some they may not even be known) and they have been adapted and transformed over time, they have nonetheless been taken for granted as “universal stories” that are fixed once and for all. However, the proposed act of fortune-telling based on these stories might offer an alternative dynamic and alter the status of such myths. The act of fortune-telling involves a subjective reinterpretation and reiteration of mythical stories directed toward one's past and future. In this respect, it provides the opportunity for a subjective re-interpretation of a culturally shared story. However, the act of the narrator entails not merely a recitation but a re-enactment of the story, which is fused with the personal experiences of the fortune-seeker that distort and re-narrativize the story anew each time it is presented.

As for the divination offered by the Falname, the act of fortune-telling gains additional significance in its congruence to the mythological status of the stories represented by the images. The subjective re-narrativization of such stories reclaims the dogmatic and almost objective nature of myths and opens them up to an ever-changing intersubjective interpretation by breaking their narrative closure. Hence, through the interpretation of the fortune-teller, “founding” myths such as that of Adam and Eve are brought into the present of the performance, not as a finished, commanding text but as a narrative to act upon within the present of the utterance.

Even though we cannot evaluate the ways in which Sultan Ahmed read his own fortune in the miniatures of the Falname, the practice of fortune-telling provides us with a productive reading strategy. The performance of the fortune-teller is based on his or her identifying, within the confines of the culturally transmitted codes of divination, particular details or their combinations to be signs auguring certain events. In particular, image-based divination such as tarot, coffee-cup reading, and the reading of the images from the Falname, rely on the recognition of visual details and the interpretation of them according to a textual or oral pre-text. Yet this reading entails the reinterpretation of the pre-text in relation to the image toward an interlocutor who is the subject of the divination. Therefore, the act of divination is a form of visual storytelling that, although stemming from the image, is not bounded by it, since the interpretation is directed at an external interlocutor of the story. The act of the fortune-teller is, consequently, an act of subjective re-narrativization of the image that does not necessarily coincide with a preceding text.

The transcription of the method promoted by divination into the language used in scholarly analysis of images gives us a productive juxtaposition that sets iconographic analysis beside a semiotic narrative reading based on the primacy of the pictorial detail. In order to do so, we should first discuss what the notion of the visual detail and the practice of reading in detail entail.

What Is a Detail and Where Does One Find It?

In Reading in Detail (1987), from which I take the main title of this chapter, Naomi Schor states that we “live in an age when the detail enjoys a rare prominence” (1987: 3). However, for art historians pictorial details have long been significant evidences – at least since Giovanni Morelli developed the method of paintings' connoisseurship that involved concentration on small details, such as the depiction of earlobes and fingernails.10 In her readings, which assert “the claim of the detail's aesthetic dignity and epistemological prestige” (7), Schor maintains the tension between the valorization and the denigration of the detail as the minute, the partial, and the marginal. She writes:

To read in detail is, however tacitly, to invest the detail with truth-bearing function, and yet as Reading in Detail repeatedly shows, the truth value of the detail is anything but assured. As the guarantor of meaning, the detail is for that very reason constantly threatened by falsification and misprision. (7)

Here, Schor refers to the intrinsic paradox of the detail. The detail can be taken as the “guarantor of meaning,” or tacitly as the “bearer of truth,” yet it can never be exempt from falsification because of its marginal position, which fails to master a narrative. Oscillating between guaranteeing meaning and permanently falsifying it, the detail is marked by an ambivalence inextricably linked to the viewer/reader's position as the producer of meaning.

While Schor's textual details are tainted by ambivalence, visual details are even trickier. This is not only because of the semantic undecidability between the visual detail's truth-value and the everlasting misprision that marks it with instability. The notion of detail is a comparative one. Something can only be considered a detail in relation to or in comparison with something else. First, viewed under the rubric of a formal category, a detail might be relatively small-sized in comparison to other figures...