![]()

1

Sofia Coppola: Postfeminist [d]au[gh]te[u]r?

‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.’1

‘Explicitly and implicitly, women are instructed by their environment (from the school room to the women’s magazine) in how to “become” a woman – a task that is never completed and subject to constant revision.’2

‘[My films are] sort of about a lonely girl in a big hotel or palace or whatever, kind of wandering around, trying to grow up.’3

Postfeminism and Girlhood

For feminist theory and politics, the question of how a baby comes to identify first as a girl and then as a woman is of crucial importance. As the quotes above show, feminist theorists such as Simone de Beauvoir and feminist film scholars such as Hilary Radner figure this identification as a complex process of becoming – a becoming that film director Sofia Coppola names as both a ‘wandering around’ and a ‘trying to grow up’, her phrasing capturing the lack of direction, ambivalence and difficulties for girls becoming women. In a society in which gender difference is attributed cultural and sociological as well as biological meaning, the frameworks which guide the process of learning which gender one is have the power to either reinforce or overcome prejudice, inequality and oppression. For girls, feminism seeks to provide positive role-models to enable them to feel proud of their gender identity rather than constrained by it. However, it also has the more negative task of identifying how a patriarchal system can still oppress girls and women. Early feminist film theory that emerged in the 1970s developed in response to both these traditions, with on the one hand the so-called ‘positive images’ criticism calling for aspirational and non-stereotyped images of women in film, epitomised by the cultural studies/sociological work of Molly Haskell and Marjorie Rosen, and on the other critical accounts of cinema itself as a tool used to idealise and objectify women that needs to be rethought in a non-patriarchal way, associated especially with the psychoanalytic methods of Laura Mulvey and Claire Johnston.4 These theorists had a direct impact on film-making, what Mulvey described as theory’s ‘utopian other’.5 Feminist possibilities in film oscillate between two poles of a radical avant-garde committed to destroying visual pleasure and creating a non-patriarchal counter-cinema, and a more entertainment-led narrative approach intended to record the realities of women’s lives and agitate for social change.

Since the heady days of the first Festival of Women’s films, held in 1971, the identity and context of women’s film-making has changed enormously, to the extent that it can no longer be labelled ‘utopian’ or ‘feminist’. Partly, this is because there are simply more women film-makers, with directors such as Andrea Arnold, Catherine Breillat, Kathryn Bigelow, Nancy Meyers, Nora Ephron, Sally Potter, Jane Campion, Agnès Varda, Isabel Coixet, Diane Kurys and Lucrecia Martel testifying to the range of films produced across nations, and in commercial, art-house and subsidised cinema.6 Such a narrative of female progress would seem to chime perfectly with the dominant cultural mode of postfeminism and its diffusion in the cinematic sphere. This holds that the demands of feminism, for example for a specific support for, and encouragement of, female filmmakers, are not necessary, as women have succeeded in making films, demonstrating that we now live in an era of gender equality. Hollywood also makes films that target a female audience. Far from being either avant-garde or social realist, it is a ‘chick’ postfeminist sensibility that informs such paradigmatic films ‘for women’ as Bridget Jones’ Diary (Maguire, 2001), The Devil Wears Prada (Frankel, 2006) and Sex and the City: the Movie (King, 2008).7 Generally speaking, the postfeminist takes for granted the goals and gains of second-wave feminism as concerns women having the right to paid employment and the vote, but rather than rejecting femininity, delights in such ‘feminine’ pursuits as shopping, wearing make-up, and pursuing (usually) heterosexual romance. Rosalind Gill defines the postfeminist film as one in which there are recurrent themes, tropes and constructions centred on the (female) body and its need for constant surveillance and discipline, the dominance of the makeover paradigm, a marked sexualisation of culture, and the awkward entanglement of feminist and anti-feminist ideas.8 For Hilary Radner, this sensibility owes less to the solidarity and sisterliness of the 1970s feminist movement than a parallel movement which grew up alongside it. She labels this ‘neo-feminism’, which she sees as having had far more impact on the postfeminist cultural landscape than feminism, particularly in its emphasis on the individual. Both feminism and neo-feminism argue for women’s right to financial autonomy and self-determination, but whereas feminism placed this within the context of state interventions and social justice, neo-feminism is more closely aligned with neoliberalism, the dominant ethos of the twenty-first century. Neoliberalism assumes that empowered individuals can exercise choice and agency to reach their goals, and takes no account of institutional constraints. While Radner states that Gill’s definition of the traits of postfeminist film is an accurate analysis of the content of many films aimed at women, she explains the importance of understanding these films as neo-feminist rather than (or as well as) postfeminist is that they allow us to see how while they have picked up on some of the second-wave’s rhetorical devices, such as the right of the individual feminine subject to self- determination, they are not so much hostile as indifferent to the social and political concerns that set feminists apart from a general group of female strivers attempting to achieve the ideals of neoliberalism. Neo-feminism, she posits, is only very tangentially a consequence of feminism, but rather shares neoliberalism’s concern with consumer culture as one of the dominant means through which a woman ‘can affirm her identity and express herself’, thus constituting ‘a very attractive version of feminine culture in terms of the needs and designs of the media conglomerates that dominate the contemporary scene.’9

For Radner, films that are neo-feminist dominate what she labels Conglomerate Hollywood’s notion of films that are aimed at a female audience.10 They repeat a significant number of traits: a charismatic female star as the focus of the diegesis, often portraying a professional working woman; an emphasis on fashion and consumer culture; the disappearance of chastity as a ‘feminine virtue’; romance as a significant theme; the ‘do-over’ [makeover] as a solution to seemingly insurmountable problems. Radner dubs these ‘girly films’, in order to underline their close relations to a feminine ideal that is represented through ‘girlishness’ as a mode of appearance and a way of being. Although as Radner explains, girlishness is not necessarily correlated to biological age, its importance as a signifier of the feminine ideal indicates just how important the figure of the girl is in neo-feminist and postfeminist culture.11 For feminist discourse, the girl is a problematic figure. As Catherine Driscoll explains:

feminist practices […] are still dominated by adult models of subjectivity presumed to be the end-point of a naturalised process of developing individual identity that relegates […] roles, behaviours, practices to its immature past. As a future-directed politics, a politics of transformation, girls and the widest range of representation of, discourses on, and sites of becoming women are crucial to feminism. Yet feminist discussions of girls rarely engage with feminine adolescence without constructing girls as opposed to […] the mature, independent woman as feminist subject […] shaping a dominant feminist address in norms of independence, agency and originality that while liberatory for some also works to restrict and homogenise the category of women.12

In contrast, youth and girlishness are prized within postfeminist culture, and while this obviously could work to infantilise and belittle adult women, it can also enable a more open and flexible approach to what Driscoll labels ‘the sites of becoming women’. Radner explains that reclaiming the figure of the girl and girlish pursuits underlines the unwillingness of (many) women to reject femininity. A neo-feminist paradigm offers a way to retain femininity even as its definition evolves with rapid social and economic change.

In postfeminist popular culture, the figure of the girl is hypervisible. Identified as beginning with the emergence of ‘girl power’ in the 1990s, which co-opted a certain version of liberal feminism and sold it to young girls as attractive and empowering, the girl has become an increasingly visible figure in popular culture. Sarah Projansky argues that thinking about girls is not a new cultural phenomenon, but rather that it ‘draws on a long standing tradition of focusing cultural attention on girls as problems, as victim of social ills, as symbols of ideal citizenship, and as all round fascinating figures.’13 What is new is an intense and sustained focus on girls, often characterised as ‘new girl heroes’ or ‘icons’: as well as the Spice Girls band, the 1990s also saw for example Nickelodean’s ground-breaking series Clarissa Explains it All (1991–94) which initiated a new trend in children’s TV programming for female heroes, challenging the logic that said children’s shows with girl leads could not be successful and rippling out to such figures as Buffy, the Vampire Slayer; Sabrina, the Teenage Witch; Princess Merida in Disney’s Brave (Andrews, Chapman and Purcell, 2012) and Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games franchise (Ross, 2012+). As Projansky comments, ‘the current proliferation of discourse about girls literally coincides chronologically with the proliferation of discourse about postfeminism.’14 Projansky attributes this to five main factors: first, both postfeminism and girlness can be seen as part of a focus on youthful femininity in culture; second, this cultural obsession with girlhood could be seen as backlash against a certain 1980s version of feminism associated with serious business women and ‘power-dressing’ – girls haven’t yet learned they can’t have a career and a family and retain a ‘sense of fun’; third, postfeminism itself is intensely invested in girlhood as what Diane Negra and Yvonne Tasker characterise as a site of transcendence and escape from adult pressures, so that girlhood becomes a highly attractive space for all postfeminist women, regardless of age;15 fourth, turning to girls is a way to keep postfeminism fresh and interesting, within the context of a corporate commodity culture; lastly, as the girls visible in the media today are the daughters of postfeminists themselves, anxieties about their future becomes a way to debate the very terms of postfeminism itself. Many of the ways popular culture represents girls and girlhood work through questions about postfeminism and its effects on the gendered organisation of present and future society.

A Postfeminist Cinema of Girlhood: Sofia Coppola

In this book, I suggest that one of the most dynamic and insightful bodies of work to address the figure of the girl in contemporary cinematic culture, and her role as lynchpin in neo-feminist/ postfeminist debates concerning agency, subjectivity and empowerment, has been produced by the film maker Sofia Coppola (b. 1971). Coppola’s films consciously address the difficult job of growing up female, and attempt to carve out new spaces for the expression of female subjectivity that embraces rather than rejects femininity. The vulnerable, childlike and abject associations of girlhood are not denied, but held in careful counter-balance with forthright examination of its pleasures and possibilities, although just how precarious this balancing-act is illuminated through the contradictions of Coppola’s own authorial persona. A key question this book addresses is the extent to which this acknowledgement of vulnerability and feeling, alongside a celebration of pleasure in girlhood, is enabled by privilege. A further point to consider is how the films enable access for audiences to a point of identification with this essential ambivalence of girlhood. In such a way, the films are postfeminist in their embrace of femininity, but also offer an apparatus to gain critical purchase upon its repeated motifs of sex, travel, shopping and makeovers as empowerment pure and simple.

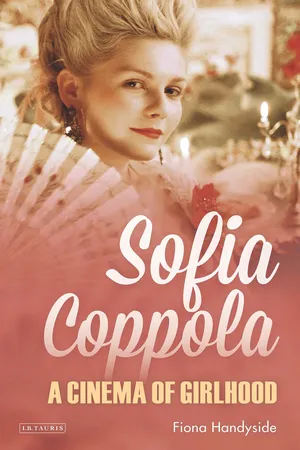

Rather than developing a counter-cinema feminist aesthetic of ‘destroying pleasure’, Coppola invents a quintessentially postfeminist aesthetic which takes femininity seriously and offers sustained, intimate engagements with female characters. The recurrent themes and motifs of her films – celebrity culture; fame; power; fashion; travel – are central questions of the postfeminist age. Girls and women are encouraged to celebrate their equal access to paid employment, political representation, sexual enjoyment and the outside world, thanks to feminism, while simultaneously considering the movement passé, outmoded and irrelevant to their twenty-first-century lives. All Coppola’s films pay close attention to the experiences of girls and young women (her youngest protagonist is 11, her oldest 25 – notably played however by an 18 year-old, giving her a remarkably youthful appearance). Her debut short, Lick the Star (1998) explores the petty rivalries and jealousies among a gang of school-girls; her first feature, The Virgin Suicides (2000), concerns a beautiful group of teenage sisters; Lost in Translation (2003) features a young newly-wed abroad and lonely who bonds with a much older man in a chaste May-December romance; Marie Antoinette (2006) is a sympathetic biopic of the teenaged queen; Somewhere (2010) recounts the activities of an eleven year-old daughter of a movie star; The Bling Ring (2013) is the study of a group of high school girls (and one boy) involved in celebrity burglaries. Even in this brief précis of her output, her films’ sympathetic engagement with the experiences, dilemmas, fantasies and desires of girls and young women shines through. Indeed, so strongly is Coppola identified with youthful femininity that this becomes an optic through which all her cultural interventions are read. In what could potentially be seen as evidence of auteurist excess, but equally speaks to the niche Coppola has carved out in the popular cultural landscape for herself, her curation of a photography exhibition in Paris in 2011–2012 is analysed as a feminisation of that most stereotypically homoerotic and male centric of photographers, Robert Mapplethorpe. Coppola avoided his best known work, instead featuring series of horses and portraits of children and women (Patti Smith, Marisa Benson). A wonderful black-and-white photograph of a young woman, Lisa Lyon, wearing a bikini and a snorkel speaks to Coppola’s project in challenging stereotypical views of femininity; Lyon’s bikini clad body is in contrast to her direct, serious, confrontational gaze mediated through her diver’s mask. As Jean-Max Colard writes, ‘the director has managed to appropriate Mapplethorpe’s photographs for herself, to slip some of her own personal universe into them, both her fiction and possibly even her self-portrait. This is how to talk about yourself through the work of another.’16

Of course, Sofia Coppola’s auteur status and image is not just informed by her films and allied cultural work. She grew up in the cinema, and her image and its meanings have been codified practically from her birth. She first appeared on screen as a baby boy, Michael, at the culmination of The Godfather (1972), her father, Francis Ford Coppola’s, critically acclaimed film based on the novel by Mario Puzo. She is baptised on-screen, in a sacred ceremony marking the importance of birth and the continuity of family both within the story world of The Godfather and within the ‘real world’ of the Coppolas. Within the complex narrative of The Godfather, s/he unknowingly provides a vital service for her uncle and literal godfather Michael Corleone, as the baptism provides him with an alibi while his ‘soldiers’ are out murdering the family’s enemies during the ceremony. Of course, she also unwittingly provides a service for her father, available to ‘perform’ for him in the film which would make his career. Her involuntary transvestite performance nicely captures the paradoxes and privileges of her position within global contemporary cinematic culture. On the one hand, she is welcomed, both on and off-screen, into a highly influential family, bound not only by ties of blood but also loyalty and business. On the other hand, she is marked from the very start as being from this family, contained by its meanings, and...