![]()

![]()

In this chapter I sketch some of the contours of the film semiotic discourse in 1970s British film culture, particularly from the first half of the decade. Although I proceed in broadly chronological order, this does not purport to be a definitive narrative. Nor is it supposed to be another account of 1970s film theory centred on Screen.2 Instead, the aim is to trace some of the crucial figures, texts (translations and critical essays), publications, pedagogical spaces and institutions, almost all centred on London; and to give an idea of a certain trajectory, concluding with the importance of semiotics for the politics and aesthetics of a number of independent films in Britain in the period. While I do not wish to imply that semiotics occupies a unique place in film theory, since it is essential to realise the way it came into contact and reacted with other methods, practices and systems of thought (notably those of radical politics, of independent and avant-garde film production, of other intellectual paradigms such as psychoanalysis and Marxism), in this manner sinking so deep into the soil of film culture that many of the most valuable texts and films do not immediately appear as easily labelled ‘semiotic’ works, the objective is to isolate it in order to highlight its specificity.

The developments of the 1970s in the UK are in fact traceable to movements in French and Italian thought in the 1960s. Rather than providing a broad outline, I merely point to the 1964 issue on ‘Recherches sémiologiques’ of the French journal Communications, published by the École Pratique des Hautes Études, which was to have significant repercussions in Britain, as a microcosm, a sourcebook for the most important issues and approaches.3 As well as essays by Claude Bremond, Christian Metz and Tzvetan Todorov, and Roland Barthes’s ‘Rhétorique de l’image’, this issue contained Barthes’s ‘Éléments de sémiologie’ in full, a work that Peter Wollen – a central figure in the history narrated below – states ‘swept me off my feet’ when he read it in Communications.4 Barthes’s text was translated into English as a book in 1967.5 Though Elements of Semiology says almost nothing about cinema, its impact can be seen in the fact that it was the core text for the 1974 British Film Institute/Society for Education in Film and Television (BFI/SEFT) seminar series on semiotics devised by Ben Brewster, and the first work listed in Kari Hanet’s introductory semiotics bibliography published in Screen the same year.6 It is likely that Elements of Semiology also led British theorists to the earlier texts Barthes uses as his basis, such as Ferdinand de Saussure’s Course in General Linguistics and Louis Hjelmslev’s Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, which had already been translated into English but are little referenced in British writing on cinema before the late 1960s.7

Christian Metz’s essay in this issue of Communications – his most influential early work, ‘Le cinéma: langue ou langage?’ – is hardly less crucial. Even before they appeared in English, the ideas of Metz, one of Barthes’s students, were discussed at length by Wollen in two texts that comprise the central early Anglophone encounters with semiotics in the field of film: ‘Cinema and semiology: some points of contact’ and the chapter of Signs and Meaning in the Cinema titled ‘The semiology of cinema’. The first of these was presented to a BFI Education Department seminar, published in the magazine Form in 1968, and again in Working Papers in the Cinema: Sociology and Semiology, edited by Wollen the following year.8 Signs and Meaning in the Cinema appeared in the British Film Institute Cinema One series, also in 1969.9 Across these two texts, Wollen provides an introduction to and critique of Metz’s ideas, placing Metz’s work in the lineages of both film aesthetics and the semiotic enterprise as a whole, with particular reference to Saussure and C.S. Peirce. Stephen Heath, who like Wollen would shortly be on the editorial board of Screen, gave a BFI Education Department seminar in 1970 envisaged as an introduction to cinema semiotics and to Metz’s work in particular.10 For a brief time, then, there was the somewhat curious situation that English-language critical scholarship on Metz existed, but English translations of his works did not.

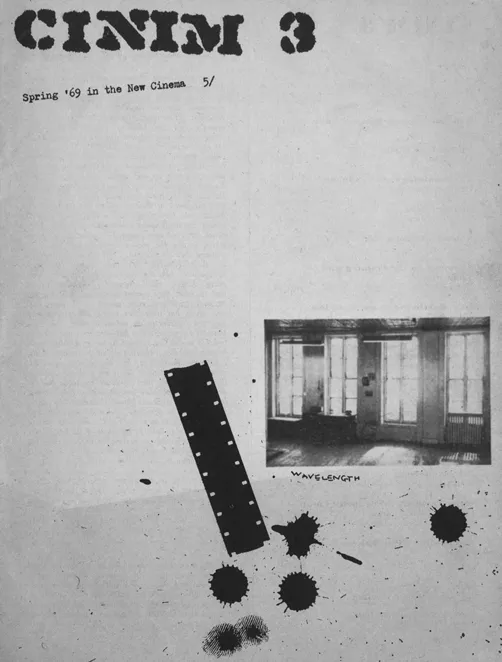

Instead, perhaps the first text of film semiotics to be translated into English, at least in the UK, is one by Pier Paolo Pasolini that appeared in 1969 in Cinim (see Figure 1.1), the magazine of the London Film-Makers’ Co-op, under the title ‘Discourse on the shot sequence, or the cinema as the semiology of reality’, originally a paper given at the 1967 Pesaro Film Festival.11 (The Italian festival was another decisive locus for the development of film semiotics.)12 The year 1969 also saw the publication of a book of interviews edited by ‘Oswald Stack’ (a pseudonym for Jon Halliday, later on the Screen editorial board), in the Cinema One series, Pasolini on Pasolini, which disseminated some of the director’s semiotic reflections to a wider audience.13 Critical engagement with Pasolini’s theories can be found at the same time in the magazine Cinema, published in Cambridge.14 In 1970, Umberto Eco’s ‘Articulations of the cinematic code’, a paper given at the same 1967 Pesaro Film Festival, was translated and published in yet another little magazine, Cinemantics (the fusion of ‘cinema’ and ‘semantics’ in the magazine’s name bespeaking the semiotic or linguistic influence).15 The Eco and Pasolini texts in Cinemantics and Cinim are both accompanied by explanatory notes as a gesture to the newness of the concepts they contain. Those for Eco’s essay are provided by Peter Wollen; his notes go beyond mere exposition into critical commentary, reinforced by their appearance in the magazine not as footnotes but as comments in the margin, as annotations.

Taking these texts as a group, something of a contextual network should be visible. Much of the writing in question was in short-lived magazines with small print runs (Cinim and Cinemantics both ran for only three issues, for instance). Each magazine situates semiotic theory in a slightly different discursive framework: Cinema has significant Hollywood proclivities for example, while Cinim and Cinemantics, importantly for what follows, place it alongside writing on the avant-garde.16 As well as this independent publishing culture, a state institution – the BFI Education Department – is central, not merely through its Cinema One and Working Papers publications, but also via the forum of the Education Department seminars.17 It is worth reflecting on the reasons for the interest being paid in the UK at this time to semiotics. The texts by Pasolini, Eco and especially Metz were seen as perhaps able to meet a need already felt in some British film writing – the need for a systematic method and nomenclature for talking about cinema. As early as his first published article in 1963, Wollen laments the futility of approaching investigations of film ‘unarmed with any methodology’.18 The same felt need is discernible in the exploration of other ‘new’ methods, particularly Structuralism in the late 1960s and early 1970s,19 and Russian Formalist concepts in the early 1970s.20

Despite such claims, there were problems with Pasolini’s, Eco’s and Metz’s early work (the essays of 1967 and before collected in the first volume of Essais sur la signification au cinéma) that were acute for writers such as Heath and Wollen. The gravest issues were Pasolini’s and Metz’s interconnected realist and mystical or romantic tendencies, which in both cases gestured to a continuity with André Bazin’s understanding of cinema.21 For Pasolini, reality and filmic representation basically collapse into one another: ‘The cinema is a language which expresses reality with reality. So the question is: what is the difference between cinema and reality? Practically none’.22 Elsewhere he states, in high Bazinian mode, ‘I believe in reality, in realism’, and that ‘God, or reality itself’ speaks through cinema.23 Despite the rigour and systematicity of Metz’s work, which had already ensured it a fundamental place in British debates, his early writings separate signification from expression and assign film’s visual regime to the latter sphere: the meaning of film’s mode of representation is natural, global and continuous, immanent to objects, rather than conventional, discrete and pertaining to the realm of ideas.24 The stance that emerges, Wollen argues in Signs and Meaning in the Cinema, is a romanticism banishing conceptual thought and justifying a realist aesthetic.25 Without wishing to imply that the journal had a simple, single position, one can see how such ideas would be anathema to many of the writers associated with Screen, as Wollen and Heath very soon would be – Screen being the discursive space most identified with cinema semiotics in the 1970s. On the one hand, they run up against Screen’s general anti-realist, anti-Bazinian problematic. On the other, they sit badly with the journal’s aspirations to scientificity.26

The collection Signs of the Times, containing translations of Barthes and Julia Kristeva, was published in 1971 and led to invitations to the Screen editorial board for two of its editors, Heath and Colin MacCabe.27 Meanwhile, the journal of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, Working Papers in Cultural Studies, published translations of Barthes’s ‘The rhetoric of the image’ in 1971 (from the 1964 Communications issue) and Eco’s ‘Towards a semiotic inquiry into the television message’ in 1972.28 The crucial moment for a semiotics of cinema, though, is the well-known Screen double issue of 1973, which translated two Metz essays from 1967 and 1968, a critical commentary on the author taken from Cinéthique and another by Heath, and essays by Kristeva and Todorov included for context. The issue is nearly 250 pages long and provides a glossary, bibliography and biographical notes.29 In 1974 Metz’s Langage et cinéma and the first volume of Essais sur la signification au cinéma were published in English.30 The same year, Ben Brewster, editor of Screen, devised the syllabus for a seminar series on semiotics organised by the BFI Educational Advisory Service (formerly the Education Department) and SEFT, which also published Screen. At the same time as advanced researches were being published elsewhere, then, these seminars served a pedagogical function, popularising difficult new ideas and terminology, providing a base knowledge of the field so far. The syllabus reaches back to Saussure and contains sessions on ‘Langue and parole’ and ‘Signifier and signified’, taking in ‘the whole pre-war Formalist and Structuralist tradition’ (Roman Jakobson, Nikolai Trubetskoy, Jan Mukarovsky) and postwar French Structuralist thought (particularly Barthes, but also Kristeva and Gérard Genette). Metz was pivotal because he formed part of this tradition but unlike others focused specifically on film.31

Having provided ...