![]()

CHAPTER 1

GREEK AND SYRIAC VERSIONS OF THE ALEXANDER ROMANCE AND THEIR DEVELOPMENT IN THE EAST

The history of Alexander

Is all an ancient fable now.

– Go bring on what is novel, new,

For novelty's more savoury.

Farrukhī Syīstānyī (d. 1037)1

The Greek Background

It seems that Persian and Arabic authors of the Islamic period had no access to so-called historical sources on Alexander the Great (that is, the apparently historical accounts of Arrian, Plutarch, Diodorus, Curtius and Justin – some of which are not historical, at least in a straightforward sense).2 The Arabic and Persian sources that deal with Alexander's history are based on a Greek work of popular literature known as the Alexander Romance. It is also known as the Pseudo-Callisthenes because the work has erroneously been attributed to Callisthenes, the historian in Alexander's court, on the grounds of several fifteenth-century manuscripts.3

The formation of the Alexander Romance was a gradual process. The traditional view is that the composition of the work as a single entity did not take place until the third century AD, shortly before its translation from Greek into Latin by Julius Valerius.4 The anonymous author of the Romance is believed to have been ‘a competent speaker and writer of Greek’ from Alexandria.5

The textual history of the Greek Alexander Romance is a very complicated one. The Greek work attributed to Pseudo-Callisthenes that appeared in the Middle Ages survives in three major versions known as ‘recensions’:6

(1)The α-recension: represented by a single manuscript7 dated to the eleventh century AD.8 It is the source of the Armenian version9 (c.AD 500)10 and the Latin version by Julius Valerius (c.AD 340).11

(2)The β-recension: the author of the β-recension wrote some time after the Latin translation of Julius Valerius (c.AD 340), but he was apparently unaware of the variants in the Greek source of the Armenian version.12 The β-recension is represented by three ‘sub-recensions’:

a.Sub-recension ε: (MS Bodl. Barocc. 17, thirteenth century AD): with a strong interest in Judaism (it contains the visit to Jerusalem).13

b.Sub-recension λ: a variant of the β-recension, preserved in five manuscripts. The most substantial additions are in Book III.14

c.Sub-recension γ: the longest of the Greek recensions. It follows the basic structure of α and β, but incorporates new material from ε.15

d.Manuscript L (Leidensis Vulcanianus 93): a unique variant of β with more adventures, in particular the episodes of the diving bell and the flying machine (II, 38–41).16

(3)The δ-recension: not represented by any Greek manuscript. However, it is generally believed to be the source of oriental versions (in particular Syriac, Arabic, Persian and Ethiopian). It is also the source of the tenth-century Latin translation of Leo the Archpriest, known as Historia de Proeliis.17

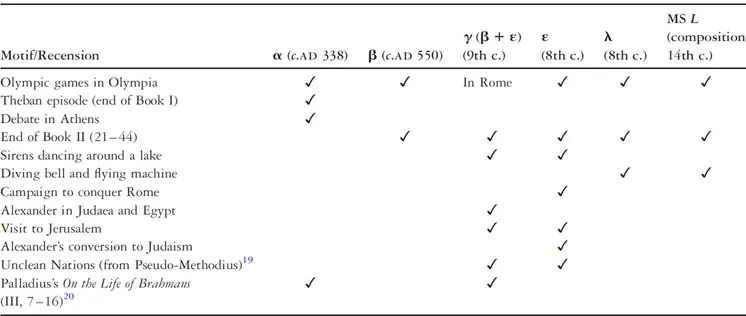

Table 1.1 Variants of motifs in later versions of the Alexander Romance18

The motifs in Table 1.1 are those that are only added to later versions of the Romance. The table shows which recension the later versions are based on. For instance, the twelfth-century Persian poet Niẓāmī is the only author who included the motif of mermaids dancing on the banks of a lake at night.21 This leads us to conclude that his source was probably based on sub-recension ɛ or γ. Another example is the Ā'īna-yi Iskandarī (Alexander's Mirror) of Amīr Khusraw of Delhi (d. 1325), in which the motif of the diving bell appears.22 Thus this implies that Amīr Khusraw had access to an ultimate source similar to manuscript L or sub-recension λ.

Syriac Sources Relevant to this Study

The most widespread Arabic and Persian traditions about Alexander are adaptations of three Syriac works – the Romance, the Legend and the Poem – which were translated at unknown but evidently early dates.23 Another Syriac text, the Laments of Philosophers at Alexander's Funeral appears as an integrated part of the tale in Arabic and Persian versions of the Alexander Romance, although it was not included in the original version. A further Syriac text is the Khuzistān Chronicle, and while it is not related to the Alexander Romance, it demonstrates the Nestorian influence at the end of the Sasanian period, when the Alexander Romance was introduced into Persian literature. It is believed that all these textual traditions became commonplace in the Syriac context within Christian communities from the seventh century AD onward.24

The Syriac Alexander Romance (Taš‘ītā d-’Aleksandrōs)

Without doubt, the Syriac version of the Pseudo-Callisthenes is the most influential of all oriental versions of the Alexander Romance, harking back to the seventh century AD.25 Wallis Budge edited and translated it into English in 1889.26 It consists of three sections that coincide with the Greek textual tradition of the Pseudo-Callisthenes. The source text was related to the Greek α-recension but differs so considerably that it has generally been reckoned to be evidence of a lost Greek recension known as the δ-recension, mentioned above. The first section contains 47 chapters, the second only 14, and the third has 24 chapters.27

There are two important aspects of this version relating to the Arabic and Persian sources. Firstly, the Syriac text offers a fairly complete and accurate account of Olympias's affair with the Egyptian pharaoh Nectanebo, as related in the Greek version, which is not found in most Arabic and Persian sources. Secondly, it describes the expedition carried out by Alexander beyond the River Oxus in Central Asia and China,28 including his visit to the Emperor of China and his adventures there (such as the dragon episode), which are also standard features of the Persian versions.29

The Syriac Alexander Legend

The Exploits of Alexander (Neṣḥānā d-’Aleksandrōs), translated into English by Budge as A Christian Legend Concerning Alexander, is a short appendix attached to Syriac manuscripts of the Alexander Romance.30 It was probably composed by a Mesopotamian Christian in Amid or Edessa,31 and was written down in AD 629–30 after the victory of Emperor Heraclius over the Sasanian king Khusraw II Parvīz.32

In this Christian Legend, Alexander becomes a Christian king who acts through God's will. The most important role of this text in the development of the Alexander Romance is the fact that the fusion of the motif of Alexander's barrier with the biblical tradition of the apocalyptic people, Gog and Magog, appears for the first time in this text.33 The story of Gog and Magog and the Gates of Alexander became a very important component of Arabic and Persian sources.

The Syriac Alexander Poem: A Metrical Discourse (mēmrā) on Alexander Attributed to Jacob of Serūgh (d. 521)

The Christian Legend was the source for a metrical homily entitled ‘Poem on the pious king Alexander and on the gate, which he built against Gog and Magog’.34 The Poem was probably composed in around AD 630–40 by an anonymous Christian author35 in northern Mesopotamia, probably in the neighbourhood of Amid.36

In this text, Alexander appears as a wise and pious king who is only God's instrument in his divine plan. This is said to be the text alluded to in the Qur'ān, which explains how a pagan conqueror managed to be praised in the Muslim holy book.37

The main content of the Alexander Poem deals with Alexander's travels to the Land of Darkness and his search for the Fountain of Life. Here Alexander starts his journey in Egypt and, after sailing for four months, he arrives in India, where the Fountain of Life is. Alexander's cook manages to bathe in the fountain when he goes to wash fish in it, but Alexander himself does not obtain immortality because he does not find the fountain. The other important element of the Poem is the ‘brass and iron door’ that Alexander builds to enclose Gog and Magog. Both motifs are important components of the Arabic and Persian versions of the Alexander Romance.

The Laments of the Philosophers over Alexander in Syriac

In the early Middle Ages, collections of sayings of various ‘wise men’ came to be attached to the story of Alexander's death, and in the course of time these gained enormous popularity both in the East, where they originated, and in the West, translated from Arabic.38

This text, which was originally an independent work, was subsequently incorporated into the Alexander Romance cycle. The Arabic texts of Ya‘qūbī (d. 897),39 Eutychius of Alexandria (d. 940),40 and Mas‘ūdī (d. 956),41 and the Persian Shāhnāma of Firdawsī (completed in 1010)42 contain the Laments. Furthermore, it is likely that the Laments were an integrated component of the Alexander Romance by the tenth century AD.

The Khuzistān Chronicle

In 1889 the Italian scholar Guidi edited an eastern Syrian chronicle that covers the late Sasanian and very early Isl...