![]()

1

Audiovisual Counterpoint

… audiovisual counterpoint, the sine qua non of audiovisual cinema.1

Fugue

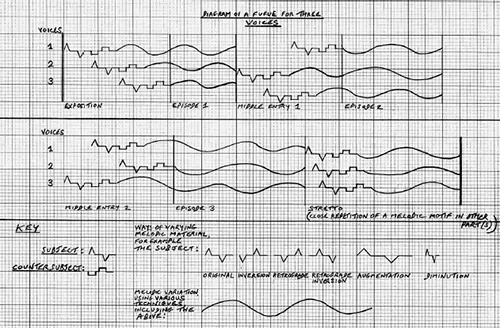

Eisenstein used counterpoint, and in particular fugue, to find a way of structuring what in 1946 he termed ‘audiovisual cinema’. Counterpoint is the simultaneous and contrasting combination of two or more melodic lines or voices, held together by common motifs and harmonies. Fugue is a complex form which makes use of counterpoint in a wide variety of ways, as shown in my diagram of the basic structure of a fugue for three voices (Fig.1). ‘Audiovisual cinema’ is Eisenstein’s concept of how the sound film should work in terms of an interaction of music, sound and film as a unified form. For Eisenstein fugue was an important formal technique for ‘audiovisual cinema’. So how can we explain Eisenstein’s passionate interest in fugue?

Eisenstein, music and synthetic art

In his Memoirs, in the ‘The Knot that Binds’ (A Chapter on the Divorce of Pop and Mom), Eisenstein recalls that after the departure of his mother, when he was eleven years old, ‘the piano went too, and I was released from my music lessons which I had just started having’. A few sentences later he explains that ‘I do not play the piano; only the radio or the wind-up gramophone.’ So his ‘playing’ of music was to be limited to listening to the performances of others, and his grounding as a practitioner would hardly have gone beyond the earliest stages. In his text The Dollar Princesss, Eisenstein confesses that he never had a musical ear. On most occasions he couldn’t recall a tune in order to sing it to himself. But at an early age, after attending Offenbach’s operetta, The Tales of Hoffmann, he could sing the melody from The Barcarolle over and over. He was also able to hear internally (but not sing) a waltz tune from another operetta, The Dollar Princess, which he first heard in Riga at the age of about twelve. His first encounter with opera was an amateur dramatic production, also in Riga, of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin. He also had childhood memories of other operas, operettas and plays: he mentions Hansel and Gretel, Götz von Berlichingen, Wallenstein’s Death, Der Freischütz, Madame sans gène, Around the World in Eighty Days, Feuerzauberei. Along with the circus (where he liked clowns the best), these were his first experiences of audiovisual performances.2

Fig.1 Schematic diagram of a fugue.

Though not mentioned in an audiovisual context, but regarding colour in cinema, Eisenstein remembers his first experiences of colour films: a Méliès underwater scene, and later, between 1910 and 1912, short educational films and episodes from the Fantômas and Vampire series. These films would have been accompanied by music, so they can also be counted as being amongst his early experiences of audiovisual work. Lastly, another significant audiovisual influence, demonstrated in the scenes set in the cathedral in Ivan the Terrible, would have been the young Eisenstein’s experiences of the services of the Russian Orthodox Church.3

However, in order to find the origins of Eisenstein’s preoccupation with fugue we need to expand the frame and to examine in greater detail a later period of artistic activity, in which there was much experimentation in the combination of visual and aural means of expression, beyond the tradition of Western opera. In some cases this ‘Synthetic art’ involved influences from the Far East. For example, in 1914 Eisenstein’s mentor, the theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold, directed a double bill of plays by the Russian poet Aleksandr Blok, comprising The Unknown Woman and The Fairground Booth, in a production which was influenced by Japanese theatre. The Kabuki and Noh traditions were particularly of interest to both Meyerhold and Eisenstein because of their highly audiovisual nature. Performances in these Japanese theatre traditions involve a tight unity of movement, colour, music and text.4

Other artists from this period shared a background in both music and the visual arts, which is reflected in their work. In the cases of Viking Eggeling and Hans Richter, this background is combined with a passion for musically inflected painting from China and Japan. In the summer of 1922, Eisenstein joined Foregger’s performance group FEKS (Factory of the Eccentric Actor). There he met Grigori Kozintsev, who later became a fellow film director.5 Kozintsev, in his book about his film of King Lear, mentions how he often went with Eisenstein to productions of the Kabuki Theatre, when it visited Moscow in August 1928. He describes how ‘Synthetic art, which was so much talked about in the first years of the revolution, was before our very eyes.’6

In the period referred to by Kozintsev, in continental Europe there were many experiments relating to the synthesis of light, sound, colour and music. In his text Vertical Montage, written and published in 1940, Eisenstein analyses one of the earliest examples of ‘Synthetic art’, Kandinsky’s The Yellow Sound.7 The Russian-born painter, a pioneer of abstract art and co-founder of the Blaue Reiter group of artists, published The Yellow Sound in the Blaue Reiter Almanach in 1912.8 This work features an almost abstract plot involving actors wearing costumes which are in various symbolic colours. Kandinsky effects an intricate interaction of music, stage lighting and action to attempt a total synthesis of music, light and colour. Eisenstein notes that Kandinsky calls this work a ‘stage composition’. He quotes extensive extracts from it, but he writes dismissively of its concentration on form at the expense of content. However, it is Kandinsky’s idea of a performed synthesis of colour and sound which caught the filmmaker’s attention. He describes Kandinsky’s ‘vague perceptions of the interplay of colours understood as music, of the interplay of music understood as colours’.9 Here Eisenstein is definitely more interested in the principle of sound and colour interaction mani-fested in ‘synthetic’ art, rather than in its actual realisation in Kandinsky’s ‘stage composition’. We shall see the far-reaching consequences of his approach.

It is this interplay between music and colour which was to inspire a significant number of artists during the 1910s and the 1920s, quite a few of whom were also preoccupied with fugue, for example the painter-musicians Adolf Hoelzel, Paul Klee and Lyonel Feininger.10 By examining the ‘synthetic’ work of these painters, we can see how the idea of a visual fugue became a feature of the experimental art world of this period. This artistic climate, which Eisenstein experienced on his trips to Germany, France and Switzerland from 1926 to 1930, would inform his own theory and practice of audiovisual cinema.

Painters and fugue

An early mention of fugue in the context of a painting can be found in the work of Adolph Hoelzel, a painter who experimented with abstraction even before Kandinsky.11 He was also a musician (a violinist) and an admirer of J. S. Bach. He developed his own colour theory, using musical terms to describe his systems of colour circles. He explained his borrowing of musical terminology by saying that musicians often used terms from painting for similar purposes. In 1916 he painted Fugue on a Resurrection Theme, an abstract painting with a rhythmic use of angular forms, evoking the closed forms of stained glass windows.12 The dominant shape in this painting is the triangle, which appears in a wide variety of types and positions. This variety of a recognisable shape corresponds to the immediately recognisable melodic motif, the subject of a fugue, which appears in various forms throughout a fugal composition. This formal technique produces an organic unity in which each part of the work is related to the whole, whether it is a painting or a piece of music.

Paul Klee, who joined the Blaue Reiter group of artists in 1912, was born into a musical family. He was also fascinated by fugue and polyphony. His father was a music teacher and his mother a singer; he became an accomplished violinist. Even after developing as a visual artist, he continued to play the violin throughout his life, occasionally in public concerts. Admiring Bach and Mozart above all other composers, Klee felt that classical music had entered a decline after the eighteenth century. He believed that ‘music was now primarily a reproductive activity; it no longer offered the creativity present at the time of the great masters.’ It was this belief which led him to become a visual artist, although he was frequently inspired by musical structures. Klee’s ambition, as stated in his diary in 1918, was to master painting to the extent that the composers of the past he admired had mastered music. His aim was to achieve in painting the clear structures and variations of themes which he found in the form of the fugue.13

Klee was also influenced by the brightly coloured Cubist paintings of Robert Delaunay, and he appreciated them in musical terms. Delaunay had been an invited participant in the exhibitions organised by the Blaue Reiter group, and his work had been reproduced in the Blaue Reiter Almanach. In the French painter’s work, Klee detected a temporal quality, resulting in a visual representation akin to a fugue: ‘Delaunay strove to shift the accent in art onto the time element, after the fashion of a fugue, by choosing formats that could not be encompassed in one glance.’14 This association of a painting with the fugue is an important idea which was developed by the artists Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling. They (and later, Eisenstein) were to make a similar connection between the traditions of Chinese and Japanese scroll painting and the fugue.

For Klee, the temporal aspects of a painting had a greater spatial quality than was possible in music. He called this type of art ‘polyphonic painting’. This involved a significant correspondence between the space in a picture and the passage of time. ‘Polyphonic painting’ could be realised in various formats, horizontal or vertical, but they all had in common the characteristic that they could not be grasped in a single instantaneous glance. Klee’s use of the term ‘polyphony’ also implies that in this synthetic form of art more than one ‘voice’ appears simultaneously – these voices are shown in visual and spatial terms, and they are analogous to melodic lines in a musical score.15

Klee’s watercolour Fugue in Red (1921) is a good example of ‘polyphonic painting’. Here the repetition of various shapes evokes the visual equivalents of canonic imitations, where the echoing of melodic motifs are expressed by the close repetition of shapes in the painting. Melodic inversion, the turning upside down of melodic patterns, is shown in shapes which are reversed in an analogous way, like the triangles in the middle and in the bottom right of the painting. Invertible counterpoint, whereby melodic material can be placed alternatively both above and below another melodic line, is found in combinations of shapes which are spatially arranged in the same way, like the rectangles at the bottom left below the vase-like shape, which appear above a similar shape on the right in the picture. What Klee achieves in such ‘polyphonic painting’ is similar to musical notation, a visual representation of a musical structure, where the space from left to right in the picture corresponds to the passage of time in a piece of music.16

During the early period of his teaching at the Bauhaus, Klee would experiment with such fugal structures in his paintings in an attempt to solve problems of visual composition by borrowing elements of this musical form. Other artists at the Bauhaus experimented with possible structural relations between fugues and the visual arts. Heinrich Neugeboren, for example, worked in a more literal manner than Klee. He made a sculptural transcription in steel of four bars from a fugue by Bach in his Plastic Depiction of Measures 52–55 of the Eb minor Fugue by J. S. Bach (1928). His intention was to clarify the spatial and temporal aspects of this extract from a fugue. This sculpture clearly delineates a counterpoint of three melodic lines. Reading the sculpture from left to right like a music score, one can see a canonic imitation (like a stretto) between the three voices, beginning with the lowest one. This echoing pattern is finished by the middle of the sculpture, and it also occurs with an inversion of the second part of the motif at the ‘end’ of the sculpture on the right. This echoing pattern also begins in the lowest voice. The vertical aspects of the sculpture correspond to the vertical harmonic nature of the fugue. These vertical aspects support the melodic outlines of the motifs. By using his sculpture to ‘analyse’ this extract from a Bach fugue, Neugeboren could not only hear more distinctly what was happening in the music at this point, but he could also see its spatial and temporal aspects more clearly than with traditional music notation. In this intention he echoes Klee’s belief that the temporal aspects of a painting could be shown to have a greater spatial presence than was possible in music. Neugeboren has thus moved beyond Klee’s idea of ‘polyphonic painting’ to make a three dimensional ‘polyphonic sculpture’.17

With Klee at the Bauhaus was another musician-painter, Lyonel Feininger, who composed fugues for organ which were performed in Germany and Switzerland between 1921 and 1926. Like Hoelzel and Klee he had a strong musical background. Like them he also had a special affection and admiration for the music of J. S. Bach. Music was so important to him that he stated, ‘Without music I cannot see myself as a painter.’ However, he professed not to be interested in expressing music in terms of painting, acknowledging that many artists had attempted to do this. Instead he confirmed his interest in polyphony, which when ‘paired with delight in mechanical construction, went far to shape my creative bias’.18 This statement is comparable to Eisenstein’s fascination with the polyphonic nature of the building of a pontoon bridge, which he witnessed as a young trainee engineer during the First World War. In Nonindifferent Nature he described the coordinated efforts of each student engineer, which ‘merge into a single general production, and taken all together, are combined in an amazing orchestra counterpoint experience of the process of collective work and creation’.19

It was inevitable that some of these painters with a strong musical background should become involved in making the first experimental films. It was a short but daring step to shift from making abstract visual art structured by musical forms, to adding an actual tempor...