![]()

1

The Doom of a Generation?

Unless it is cleaned up within this generation, [cinema] will undermine every existing agency for decency and public order.

R.G. Burnett and E.D. Martell,

The Devil’s Camera (1932)

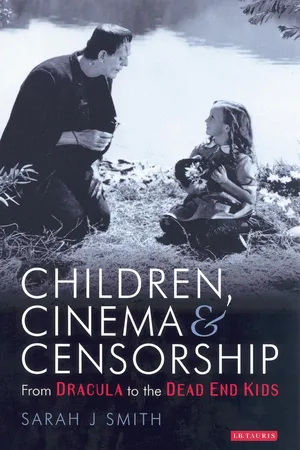

In 1937, a new American film was passed with an A certificate by the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) for distribution in the UK. This certificate, given the previous year to horror films such as The Walking Dead (1936) and Dracula’s Daughter (1936), informed cinema managers and patrons that the film was not considered suitable for children under 16 years old, unless they were accompanied by a parent or bona fide adult guardian. The new film in question was Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Thousands of children would flock to see it on its first release in Britain and, as will become apparent, the majority were probably quite undeterred by the BBFC’s attempts at regulation.

During the 1930s, authorities in Britain and across the world struggled with the issue of children’s cinema-going. At one extreme, moral watch-dogs prophesied the doom of a generation corrupted by the influence of the silver screen. At the other, champions of the cinema declared its positive educational and social value to young people. Meanwhile, children became one of the largest audience segments in cinemas worldwide.

The debate surrounding children and film did not exist in isolation – it simply represented a peak in longstanding controversies over children and leisure which had been endemic across Europe and the USA for hundreds of years. Some argue that this debate might date back over 2,000 years to Plato, who suggested that poets should be banned from his ideal Republic, so that their stories about the questionable behaviour of the gods would not damage the vulnerable minds of children.1

Certainly, since at least the eighteenth century, a cavalcade of pastimes and technologies have been deemed undesirable – if not dangerous – for children, including penny magazines, playing in the street, fighting, dancing, gambling, sex, radio, cinema, television, comic books, rock music, videos and computer games. All have been cited as threats to children’s safety, health, morality and literacy and have been blamed for increases in juvenile delinquency. And the debate continues: current targets include mobile phones, gangsta rap and the Internet and it can safely be predicted that Virtual Reality will be targeted in the near future.

Fears about the social effects of new media have therefore recurred for over two centuries and the debates they generate nearly always primarily revolve around the potential impact of these media on children. Despite thousands of research projects, conferences and other enquiries (most of which find the medium in question to be intrinsically benign), these issues refuse to be resolved. And whenever a shocking incident occurs involving young people, the immediate reaction is often to blame popular culture, however tenuous the link might be – as in the bogus scapegoating of Child’s Play 3 during the James Bulger murder case, or neo-Nazi websites, television, film and the music of ‘shock rocker’ Marilyn Manson after the Columbine High School Massacre.2

In his study ‘Reservoirs of Dogma: An Archaeology of Popular Anxieties’, Graham Murdock calls for more detailed historical research into these fears and their associated debates:

If we are to develop a more comprehensive analysis of the interplay between popular media and everyday thinking, feeling and behaviour, and to argue convincingly for expressive diversity in film, television and the new media, we need to challenge popular fears. Retracing the intellectual and political history that has formed them is a necessary first step.3

As part of the ‘first step’, this book seeks to contribute to an understanding of the nature and impact of recurring debates surrounding children and media usage, by exploring one key example

– the controversy surrounding children and cinema in the 1930s.

Although the field of film and cinema history is large and growing, surprisingly little has been written about the debate over children and cinema in 1930s Britain and only a few books explore the topic at any length. The most recent is Annette Kuhn’s An Everyday Magic, a fascinating ethno-historical study of film reception during the 1930s, which often focuses on the cinema-going of children, owing to the nature of some of the primary sources involved.4 Meanwhile, an overview of controversies surrounding children and leisure between around 1830 and 1996 is presented in John Springhall’s Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panics, which includes a concise yet detailed study of anxieties that arose around gangster films and child viewers in Britain and America during the 1930s. Terry Staples’ All Pals Together also provides a narrative and nostalgic look at children and cinema in Britain between around 1900 and 1987, including some very interesting material on the 1930s.

Jeffrey Richards’ valuable and perceptive exploration of cinema-going in Britain during the 1930s, The Age of the Dream Palace, outlines the debate over children and cinema and considers, among other things, the extent to which it may have reflected middle class attempts to control working class leisure and promote hegemony. In a similar vein, Stephen Humphries analyses debates over children and leisure (including cinema) in his work Hooligans or Rebels?, strongly arguing that class, rather than age, was the key factor in perceptions of juvenile delinquency. While social class was undoubtedly a factor in debates over children’s cinema-going, I would suggest that it was by no means the most significant factor. Nevertheless, Humphries’ emphasis on resistance, and his insistence that working class children were not simply the passive recipients of social control, are critical issues that will be explored in some detail in the chapters that follow.

No other works have directly tackled the subject of British children and cinema in the 1930s, although earlier periods and older age groups have received a little attention.5 English language studies of the debate in other nations are also scarce. Anton Kaes, David Welch and Gary D. Stark have all assessed the general cinema debate of the 1920s and 1930s in Germany, but none of these authors are more than marginally interested in issues relating to children.6 Meanwhile, Richard Stites’ work on the history of Russian popular culture only mentions the subject of children and cinema in passing.7

More has been published on the subject in America, particularly concerning the major research project that dominated the American debate in the 1930s: the Payne Fund Studies. The key text in this field is the collaboration of Garth Jowett, Ian Jarvie and Kathryn Fuller, Children and the Movies.8 However, even this volume is not directly concerned with the history of childhood, as its stated aim is to research the Payne Fund Studies themselves, in order to ‘restore [them] to a place of honor in the history of communications research’.9

It is understandable but regrettable that there are also, as yet, no studies of this topic as an international phenomenon. Cinema was undoubtedly international from the outset, with inventors, financiers, producers, casts, crews, distribution networks and audiences ranging and mixing across the globe. There was also something of an international consensus regarding concerns over children and cinema in the 1930s. Common anxieties (along with opposing views of the educational potential of cinema) recurred across the board in nations with otherwise starkly different ideologies, from Britain and America to Nazi Germany and Communist Russia. For example, theories regarding the power of cinema to imbue children with a sense of political and national identity caused Americans to rail against the fascist and communist influences in European films of the 1930s, while Europeans of all political hues protested at length about the Americanising impact of Hollywood on their children. However, no work has yet been published that considers the international dimension of the debate over children and film, and sadly this book will do little to remedy the situation, although references to the international context have been made where possible.

Quite rightly, therefore, in his article on children and cinema in the 1910s and 1920s in America, Richard deCordova bemoans the dearth of literature in this field. ‘It seems odd’, he suggests, ‘that ... film history has so completely ignored the obsession with the child audience, particularly if we admit that it was the dominant feature of critical approaches to the cinema at the time.’10 Certainly, although the debates have been outlined to some extent, little has been done to investigate the motivation and mechanisms that lay behind attempts to control children’s viewing in the 1930s, or to place these attempts in their historical context regarding children, leisure and media. That is therefore a central aim of this book – to explore not only what happened, but how and why it happened.

In doing so, this book is a response to research in media and communications studies regarding controversies over children and television. For in this field, although scholars have increasingly come to recognise the cyclical nature of the debate surrounding children and leisure and, therefore, the need for historical research, little has yet been done.11 As David Buckingham argues, the key to understanding the recurring debate about children and media influence of all kinds may lie not so much in analysing the results of the empirical research, but in examining its context. Thus, he argues, research into children and television may

reveal as much about the tensions and contradictions within society as it does about either children or television. In this respect, it is important to locate the concern about the area historically, in the context both of evolving definitions of childhood and of recurrent responses to the perceived impact of new cultural forms and communications technologies.12

This book therefore aims to provide some historical background, in order to contribute to an understanding of ongoing debates regarding children and media. So far, scholars in media studies have mapped some of the historical landmarks of the debate from the air.13 Now I will explore one of those historical landmarks from the ground, by providing an extended, detailed case study of the controversy over children and film in 1930s Britain.

First, though, two fundamental questions need to be addressed. Why has the decade of the 1930s been chosen? And how are children to be defined?

Moving pictures were introduced to the British public in 1896 and the first purpose-built cinema in Britain was erected ten years later. Thereafter, rapid growth occurred; by 1907 there were around 250 picture palaces in Britain, after which the number virtually doubled annually, rising to 1,600 by 1910 and nearly 4,000 in 1911. British cinemas continued to expand in both numbers and size, so that by 1939 the country had over 5,000 cinemas that attracted an attendance of approximately 20 million per week.14 Cinema had become the first mass medium to be distributed simultaneously to audiences of millions and it therefore provoked much debate.

From the outset, defenders of cinema insisted that this was a highly promising form of self-improving education; an influential force of socialisation, with powerful potential for good. However, in reality, film quickly became established as an extremely popular form of entertainment rather than education, associated from the beginning with alcohol consumption, with early venues for film including travelling fairs, music halls and vaudevilles, most of which served alcohol. Furthermore, as the medium developed, its content was largely derived from the sensational narratives of melodrama and cheap literature, rather than worthy literary or educational alternatives. It was of great significance, therefore, that film became a cheap and massively attended source of entertainment, rather than improvement. Moreover, it was largely frequented by the urban working classes and, despite concerted efforts to the contrary, it was a medium principally driven by commercial interests, rather than religious, educational, or otherwise ‘improving’ ones.

Consequently, the cinema had numerous critics, mainly from middle class educational, religious and social welfare groups, who insisted that it represented a threat to society. Vulnerable, uneducated or uncontrollable viewers were considered especially at risk – namely, cinema’s most frequent patrons: the working classes, women and children. Romantic notions of childhood were invoked and movies were denounced as violent, frightening, sexually corrupt, addictive and therefore fundamentally damaging to the naturally curious, vulnerable, naïve, imitative and emotionally susceptible mind of the child. At the same time, concepts of original sin were evident in declarations that the negative influence of cinema stimulated already degenerate young minds, leading them into even greater depths of corruption, depravity and delinquency. Concerns regarding the possible influences of cinema on children and adults quickly motivated various bodies to attempt the imposition of a regulatory framework, leading to the establishment of the BBFC in 1913.

Although debates around cinema were evident from its inception, this book focuses on the 1930s because it was a key decade – arguably the key decade – in the history of cinema and its regulation. Jeffrey Richards has described it as probably ‘the least known and least appreciated decade in the history of the sound film’.15 And Peter Stead considers it ‘the most crucial period in the whole history of cinema in Britain and America’.16 It is an easily identifiable period, roughly beginning with the introduction of talking pictures and ending with the start of the Second World War. Significantly, it also is the period in which the Hays Code was developed and introduced, effecting the rigorous censorship of films (see Chapter 3). Finally, it was the decade in which cinema was established as the most popular form of communal entertainment across Europe and the USA, with children of the 1930s being regarded by many as the first generation to be fundamentally influenced by so-called mass culture.

The most important facet of the decade for this book, though, is that anxiety about children and cinema rocketed with the introduction of talkies in 1927, triggering a profusion of enquiries across the world into the influence of cinema on the young. During the 1930s, literally hundreds of surveys and reports were generated worldwide, in an attempt to assess and regulate the influence of cinema on children (see Chapter 4). Most of the ‘players’ in the British enquiries represented groups such as church and youth organisations, which were rapidly losing their virtual monopoly on organised children’s leisure. Others came from the establishments of education and government, while the remainde...