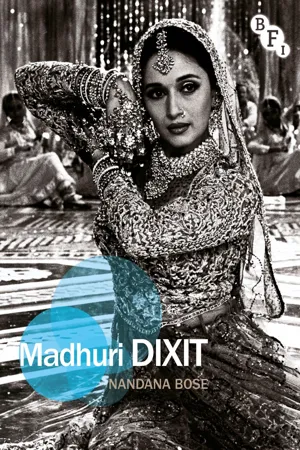

![]()

1 INDIA’S ‘DHAK DHAK [HEARTBEAT] GIRL’: RISE TO STARDOM

Brief biography

Madhuri Shankar Dixit was born on 15 May 1967 in a traditional Maharashtrian, middle-class family in Bombay (now Mumbai), in the western state of Maharashtra. Her father, Shankar Dixit, was an engineer, and her mother, Snehlata Dixit, who was artistically inclined, holds a Master’s degree in music, although her first love was dance. She has three older siblings, Bharati, Rupa, and Ajit. As a child, she and her sister Rupa learnt the classical dance form of kathak, Madhuri winning a National Talent Scholarship at the age of eleven. She participated in elocution and dance competitions, and acted in school and college plays. She recalls a happy childhood, growing up in J. P. Nagar, a modest suburb of Andheri, and having fun even though they did not own much. She reminisces being ‘totally dependent on her parents,’ and leading ‘a very sheltered protected life’ as she was the youngest in the family (Biswas 1992).

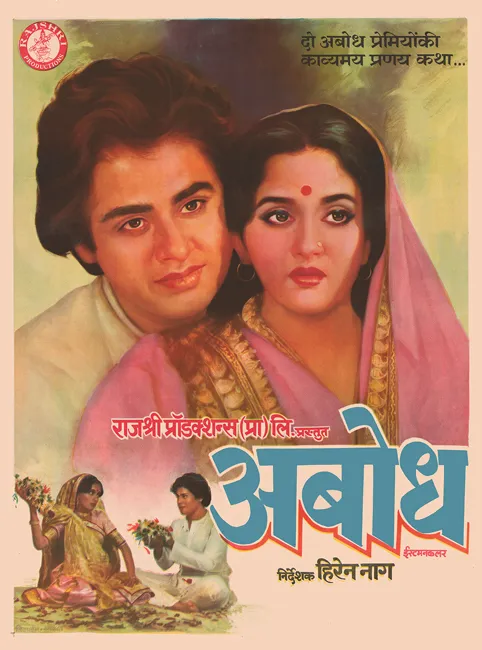

While Madhuri was in her twelfth standard at Divine Child High school, Govind Moonis, a family friend who worked as a scriptwriter at Rajshri Productions, felt she was an appropriate choice for a debutante role in their forthcoming film, Abodh (Innocent, 1984), starring the Bengali actor Tapas Paul. Moonis approached her family, after speaking with his employers, and since ‘the Rajshree (sic) people [were] known for their clean films’ (Arora 1989), they agreed, but not before asking permission from her mother’s orthodox family in Ratnagiri. Once her parents met Tarachand Barjatya of Rajshri Productions, they were appeased as it was ‘a simple and sweet role, nothing controversial’ (Rane 2010: 22). She decided to shoot the film after she had taken her school-leaving exams, since her parents wanted her to complete her education (ibid.), and then start her career at the age of sixteen. Unfortunately, Abodh was a disastrous debut. The Screen review titled ‘insipidly recycled romance’, described the film as ‘incredibly dull’, ‘sterile’, and ‘so wholesome it is almost bland and tasteless’, making passing reference to ‘the new pretty face of Madhuri Dixit making her debut as the heroine … who makes a pretty foil for her glum groom’ (1984: 4). It noted that the lead pair’s ‘chemistry somehow fails to create the right reaction, both going through the motions without much depth or conviction and losing viewer interest as a consequence’ (ibid.). However, as Madhuri did not have any ‘burning ambition to become an actress’, she treated her failed debut as a ‘passing phase and went to microbiology’ (Arora 1989), joining Parle College in Bombay while acting in two more films, Awara Baap (Vagrant Father, 1985), and Swati (1986).

The much-recounted, inspirational story of an epic struggle during her early career is an integral part of the Madhuri Dixit myth and star phenomenon. As an outsider from a non-filmi family, she made the rookie mistake of accepting bit roles in B-grade films and had the dubious distinction of surviving a string of five successive failures – Awara Baap, Swati, Manav Hatya (Murder of Men, 1986), and Hifaazat (Protect, 1987). When her sixth film Dayavaan (Merciful, 1988) flopped too, she was labelled with the ‘jinx it’ moniker (‘Heartbreaks …’ 1989: 28). It was after these failures that she felt ‘hurt’ and ‘small’ and ‘took up the challenge’ to succeed in the industry (Arora 1989). She recalls the ‘anger’ within her: ‘I couldn’t accept the fact that what I had finally decided to do, was not working out. I was absolutely determined deep down to prove everybody wrong and myself right’ (Biswas 1992), which she emphatically did four years later in 1988 with N. Chandra’s Tezaab (Acid), which made her an ‘overnight celebrity. A star was born’ (‘Heartbreaks …’ 1989: 28). It was the much-awaited ‘turning point’ in her burgeoning career after which her ‘career graph started climbing upward’ (Travasso 1990: 43).

Debut film Abodh (1984), which failed at the box office

Thereafter, she consistently delivered a box-office hit for eight successive years from 1988 to 1995, an unparalleled feat for a female star in the Bombay industry – Ram Lakhan (1989), Dil (Heart, 1990), Saajan (Lover, 1991), Beta (1992), Khalnayak (1993), Hum Aapke Hai Kaun …! (Who Am I to You, 1994; henceforth referred to by its acronym HAHK), featuring fourteen song and dance sequences. The last mentioned was Madhuri’s most successful film in terms of box-office revenue and cultural impact, winning her her third Filmfare Best Actress Award and first ever Screen award for Best Actress, in the year Screen instituted its awards (‘Madhuri Dixit: “They’re Too Precious”’ 1997: 4). It established her as a Hindi film legend, leading to more films centred around her stardom, with co-starring actors relegated to second billing such as in Raja, her next hit film in 1995. Throughout her early career she was compared to the then-reigning superstar Sridevi in a media-manufactured rivalry, while inevitably, from the mid-1990s, as she approached her thirties, she was either habitually written off or married off by the media, who were exasperated by her refusal to relinquish the mantle of top female star by dutifully tying the knot. Yash Chopra’s 1997 Dil to Pagal Hai (The Heart Is Crazy, henceforth abbreviated to DTPH) was dubbed a ‘comeback’ as younger actresses challenged her position, while she received critical acclaim in arguably her finest role as Ketki in Prakash Jha’s feminist film Mrityudand (Death Sentence, 1997).

When Madhuri tied the knot on 17 October 1999 in an arranged marriage to Dr Sriram Madhav Nene, an Indo-American cardiovascular surgeon, fluent in Marathi and, like her, an upper-caste, Konkanasth Brahmin, which was considered a ‘respectable’ alliance, the Guardian reported,

to tens of millions of south Asian men, the sense of betrayal was so great that it was as if they had been jilted at the altar. Madhuri Dixit, the reigning diva of Hindi cinema for much of the 90s, had married another … . To say that Ms Dixit has broken every male heart in the country – not to mention Pakistan and the south Asian diaspora – is to render prosaic an attachment so profound that it is at once real and imaginary, intimate and public (Goldenberg 1999).

After her marriage, she relocated first to Gainesville, Florida and then to Denver, Colorado, consequently giving up her career to become a house wife and mother of two sons, Arin and Raayan born in 2003 and 2005 respectively. The first phase of her career ended in 2002 with the critically acclaimed film, Devdas.

Away from the greasepaint for five years, she made her ‘comeback’ in 2007 with Yash Raj Studios’ Aaja Nachle (Come, Dance!) in 2007, while making several sporadic trips to India, and guest appearances on Indian media (primarily as a reality-television judge) until her permanent return to the country in October 2011. Subsequently, Madhuri has defied convention to re-create herself as a multimedia entrepreneurial celebrity in middle age by her skillful negotiation of career and family life, and of ageing; clever exploitation of the internet and social media; her acquisition of ‘super-fans’; involvement in advertising and sponsorship, charity and campaigning; and her more recent (largely feminist) films, Gulaab Gang (Pink Gang, 2014) and Dedh Ishqiya (One and a Half Romance, 2014).

Madhuri was awarded the Padma Shri, the nation’s fourth-highest civilian award, by the Government of India in 2008. In March 2011, Madhuri was honoured with a Filmfare Special award on completion of twenty-five years in Hindi cinema. In June 2012, a star in the Orion constellation was named after Madhuri by a group of thirteen members of The Empress Fanpage, including my student April Vuncannon, who presented her with the ‘star’ certificate from the Star Foundation in Mumbai (‘Star in Her Name’ 2012: 1). She has received six Filmfare Awards, four for Best Actress, one for Best Supporting Actress and one special award, and has been nominated for the Filmfare Award for Best Actress a record fourteen times. In 2014, Madhuri was named the most inspirational Female Bollywood Icon, a category nominated by the public, becoming the first to receive the honour instituted the previous year at the third annual Bradford Inspirational Women Awards (BIWA) in Bradford, UK. Her waxwork statue was unveiled at London’s Madame Tussauds in March 2012, making her the sixth Bollywood celebrity and only the second actress after Aishwarya Rai to be so commemorated, joining Bollywood legends, Amitabh Bachchan, Shah Rukh Khan, Hrithik Roshan, and Salman Khan (Indian Express 7 March 2012).

1980s industrial context

In the 1980s the Bombay film industry was in crisis, a chaotic and unprofessional work environment ‘pushed to the limits of what it could do with the systems it had. The scale of production was frenetic, with stars doing multiple movies at once’ (Wilkinson-Weber 2014: 7). Some films took years to complete, either due to a lack of reliable sources of funding or the inability of overworked stars to commit sufficient consecutive dates to finish them (ibid.: 7). Madhuri recalls how ‘disorganised’ it was during her time: ‘There were no bound scripts; dialogue was written on the set while we were getting dressed’ (Farook 2011). The 1980s were considered ‘the era of video and trashy cinema’ (Ganti 2011: 81) by the film industry, ‘a particularly dreadful period of filmmaking’, notorious for ‘cliched plots and dialogues, excessive violence, garish sets, and vulgar choreography’ which illustrated ‘the decline in cinematic quality by the mid- to late 1980s’ (ibid.).

Wax figure at Madame Tussauds London

In terms of the deeply entrenched star system of the Hindi film industry, it was a period of steady decline for Amitabh Bachchan, coinciding with the Bofors scandal, when no one male star ruled the industry, unlike the Bachchan-dominated era of the 1970s. Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan, and Aamir Khan were beginning their careers as romantic heroes in the late 1980s; family audiences were put off by gratuitous violence in the notorious ‘rape–revenge’ cycle of films, and had retreated from the increasingly shabby environs of theatre halls; and action hero-driven ‘multi-starrer’ masala films enjoyed popularity. Thus, late 1980s popular Hindi cinema proffered limited, one-dimensional, clichéd supporting roles for women; only the song and dance, and comic sequences yielded a few ‘spectacular’ opportunities for heroines to make a lasting visual impact by showcasing their talent for dancing, physical comedy, and even acting.

Mentors and collaborators

For a rank ‘outsider’ like Madhuri, negotiating a seemingly impenetrable web of intensely close kinship, familial, and interpersonal ties binding the semi-feudal industry without influential mentors would have been a near-impossible feat. This amorphous industrial structure has thwarted many starry aspirations and fledgling careers. Therefore, I contend that Madhuri’s star phenomenon should be examined in terms of a collaborative process of assemblage involving several influential male mentors and personnel (namely, the director/producer and ‘star-maker’ Subhash Ghai, producer Boney Kapoor and his brother, the star Anil Kapoor, and her manager Rakesh Nath), and creative collaborators (choreographer Saroj Khan) who took a keen personal interest in the advancement of her career, and closely collaborated with each other to relaunch, nurture, and produce a star who eventually became short-hand for ‘Bollywood’ glamour, box-office success and mass appeal. The first section of this chapter adopts an undervalued and neglected approach to the construction of Hindi film stardom that emphasises the extra-textual agencies shaping star careers by foregrounding the creative and industrial labour of Madhuri’s coterie of trusted collaborators/associates (director–manager–co-star–choreographer–hairdresser) during her protracted period of ‘struggle’ that transformed the ‘ordinary’ Madhuri into an ‘extraordinary’ star.

The role of the self-proclaimed star-maker and director Ghai, successful at the box office for two decades, from the 1980 release Karz (Debt) to the 1999 Taal (Rhythm), is particularly significant. A product of the prestigious Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), Ghai began his career as an actor in 1970 and moved successfully to direction in 1976 with Kalicharan. In 1983, he became an independent producer, establishing his company Mukta Arts, and was one of the leading producer-directors of the 1980s, helming many successful films (Mehta 2011: 160). While Madhuri was shooting in Kashmir for Sohanlal Kanwar’s film Awara Baap, Ghai, location hunting for his forthcoming film Karma (1986), visited the set and Madhuri was introduced to him by her resourceful hairdresser, Khatoon, as a ‘good dancer’. He asked if she would be interested in performing a dance in Karma and, when she agreed, shot a couple of screen tests (performing ‘one emotional scene, one comic act, a song and dance …’) in his Bombay office. She recalls being very nervous about these tests, but when Ghai informed her that he wanted to relaunch her in a leading role, requesting that she stop all the bit roles, and immediately signed her for Uttar Dakshin (North South, 1987) and Ram Lakhan (1989), she knew that it was the first step towards building a successful career (Sanjay 1986: 19). Subsequently, the dance she was supposed to perform in Karma was scrapped.

Ghai placed a six-page full-length advertisement in the leading trade paper Screen on 17 January 1986 relaunching her, and the rest is, indeed, history.1 The advertisement read: ‘Time creates history. The girl who could not succeed till 1985 … Becomes superstar in 1986 … Her name is Madhuri … Madhuri, the confidence of leading filmmakers who signed her for their forthcoming films’ (3–9). It proclaimed that six producers (including himself) – Yash Chopra, Shashi Kapoor, Bapu, Shekhar Kapoor, Boney Kapoor, K. C. Bokadia, and N. N. Sippy (in the order mentioned in the advertisement) – had signed Madhuri for their forthcoming projects, giving her flagging career a much-needed boost and raising her visibility.

There was considerable press coverage of her relaunch, which was treated as nothing short of a miracle for an actress who had been so nearly written off by the industry but was now ‘a dark horse racing towards the goal post’ (Sanjay 1986: 19). According to Deepa Gahlot, ‘if a commercially successful director of Ghai’s caliber, who was at his peak, decided to re-launch an actress, then success was assured. He gave Madhuri confidence, starting from Rajshri films (which would have taken her nowhere) to the A-list’ (personal communication, 26 June 2013).

However, despite Ghai’s high-profile promotional stunt, the flops continued, although after Ghai had signed her on for Uttar Dakshin and Ram Lakhan (which subsequently proved a box-office hit), Madhuri did continuously receive offers to work on big-banner films as a result of her influential mentor/godfather’s confidence in her talent, and her new-found visibility2 (Sircar 2011: 187). Thus, an actress was reborn as a star thanks to a promotional gimmick that eventually paid off.

During the intervening period of struggle from the appearance of the advertisement till she proved herself in her first hit film Tezaab in 1988, that she refers to as ‘her acid test’ (Mohamed 1997: 64), there were cynical print-reports declaring that even a year later she was yet to arrive (Hedge 1987: 9); describing her as ‘a “paper tiger”, until N. Chandra gave her a massive build-up during the making of Tezaab … [by calling] her the reincarnation of Madhubala, an echo of Meena Kumari’ (Mukherjee 1990: 31). Additionally, Ghai, dubbed ‘the showman who made Madhuri what she is today’, (John 1993b: 21) continued to aggressively promote his protégé to film-makers, producers, and influential male actors, and expressed great confidence in her star potential, even when producers’ interest in her fluctuated between 1986 and 1988. He is famously quoted as saying: ‘Madhuri is a volcano of talent. A highly talented girl, she possesses a finesse in dance, singing and acting. Just wait for 1987. She will be a superstar’ (Sanjay 1986: 19). His prophecy came true, albeit not in 1987 but the following year with Tezaab. History did vindicate his prediction that all Madhuri needed was one big hit and thereafter nobody could stop her (Ghai 1988). According to him, she had ‘a sound grasp of music and dance’, emoted well and ‘was improving with every schedule’. She was ‘one of the very few conscientious girls around in films … and her biggest asset [was] her discipline and dedication, her good behavior [having] stood her in good stead even when her films failed’ (ibid.).

Madhuri, in turn, agreed that it was ‘necessary to have a big name backing you [...]...