![]()

1

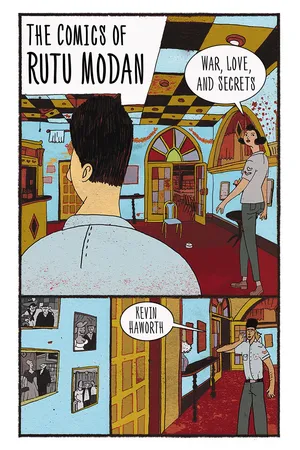

THE TRADITION OF NO TRADITION

The career of Rutu Modan, Israel’s preeminent graphic novelist, is a product of three distinct spaces: Israel, Europe, and North America. Israel, her homeland, provides her most consistent themes and her most complex stories. Europe was an early visual influence and connected her with an educated comics audience for the first time. North America is where she has achieved her greatest notice. She publishes her graphic novels with the Canadian publisher Drawn and Quarterly, has won two Eisner Awards (the leading prize in American comics), and has received rave reviews in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and other major American newspapers.

Reading her work yields much about contemporary Israel and about Modan’s sophisticated narratives and colorful drawing style. But her work is also a case study in how a comics scene can grow from modest beginnings in a small country to one that achieves international notice. Largely because of Modan, Israeli comics have grown from just a few marginalized practitioners to a dynamic field with connections to Israel’s literature, film, visual art, and education.

In 2010, Modan was asked by the Israeli Cartoon Museum when she began to make comics. “At age 5,” she answered, “though I didn’t know it. I had not yet encountered comics” (“Rutu Modan,” in X + Y, 212). Modan drew in a way that linked text and image from a very young age, with few comics to guide her, and no vocabulary to give name to what she was doing. Comics artists in Israel, at least until recently, have found their way to the medium through a variety of paths, but a common theme is the lack of a comics field, and few consistent publishing opportunities to engage and support their work.

For most of Israeli history, the country had no comics profession. Cartoons and comics in Hebrew arose before the founding of the State of Israel (1948), but these images and stories were always produced in service to other cultural goals, not as a stand-alone art form. The first Hebrew comics were made for children. In the 1920s and 1930s, one-page Hebrew comic strips began to appear in Zionist children’s magazines in Europe and quickly made the jump to Mandatory Palestine (Fink 129). Hebrew comics were a part of the larger identity-building exercise that occupied many of the halutzim—the Jewish pioneers who immigrated to Mandatory Palestine in ever-growing numbers in the early part of the twentieth century (Gaon 7). For these immigrants, establishing a national identity built on new cultural norms was as important as physical constructs such as the founding of Tel Aviv, the first modern Jewish city, or the invention of the kibbutzim, the farming collectives that established Jewish settlement outside urban areas. These new cultural norms distinguished Jewish settlers in Palestine from their European origins and the image of Diaspora Jews as a weak, second-class population. Where the European Jew was bookish and slight, the halutz was strong; the European Jew was religious, but the pioneer was proudly secular; in Europe, Jews spoke Yiddish as their lingua franca, while in Palestine, Hebrew was liberated from the synagogue and made the language of the cowshed, the café, and the newspaper.

Hebrew children’s literature of the period played a crucial role in forging a national identity based on these values (Amihay). The first Hebrew comics appeared in children’s magazines in the mid-1930s, and the stories and characters reflected two Zionist priorities. The first was to celebrate the characteristics of the new, native Hebrew child: self-confident, adventurous, strongly connected to the Land of Israel. The second was to teach Hebrew to new immigrants and their children, and to reinforce Hebrew as the language of everyday use. In 1935 the comic strip Mickey Mauo and Eliahu, by Emanuel Yaffe, began appearing in holiday editions of Itonenynu li-ktanim (Our magazine for little ones). The strip featured the adventures of the cat Mickey Mauo, a rather obvious derivative of Disney’s popular American mouse, and his child companion Eliahu.

More notably, the next year saw the appearance of Uri Muri, the first important comic strip character in Hebrew comics. Uri Muri was the product of two significant creators: the illustrator Arieh Navon and the writer Leah Goldberg. Navon was a popular caricaturist for the daily Hebrew newspaper Davar, the organ of the Labor Party. As the newspaper of Israel’s governing political party, Davar enjoyed a huge readership and unparalleled cultural influence in the Yishuv (the pre-State Jewish community). In 1936 the newspaper began publishing Davar li-yeledim, a children’s weekly magazine, with a focus on developing its young readers’ literary sensibilities as well as their Zionist values (Weissbrod and Kohn). Its editor Itzhak Yatziv invited Navon to create material for the new children’s magazine. Navon, in turn, partnered with Goldberg, already a highly regarded poet and beloved children’s author. Their first and most famous creation was Uri Muri, “the first native Hebrew-hero-child” (Gaon 11). Over the course of his long-running adventures, Uri Muri tackles specifically Zionist challenges such as teaching Hebrew to recent immigrants, draining the swamps of the Hula Valley, and devising ways to solve urban overcrowding, always with the plucky persistence and ingenuity recognizable from other Zionist cultural productions. Uri Muri’s popularity led Navon and Goldberg to create a number of spin-off characters and related strips, including the mischievous Muri Uri, the bumbling Uri Cadduri, and the diligent Ram Keisam. These comic strips shared the pages of the children’s magazines with short stories, poems, quizzes, trivia, and puzzles.

Uri Muri lasted for thirty-one years (1936–67) in the pages of Davar li-yeledim. The dominant children’s magazine of its era, Davar li-yeledim occupied a central place in the period before the founding of the State of Israel and in the formative years of the new nation (Amihay). Uri Muri and other long-running comics characters became fixtures of Israel’s visual vocabulary and history. They were immediately recognizable to multiple generations of Israeli children, and part of the cultural landscape for Jewish immigrants to Israel, who came in enormous numbers from Europe in the 1930s and 1940s and from Arab countries in the late 1940s and 1950s.

While Navon and Goldberg are notable for their long association with Davar li-yeledim, their connection to children’s literature is not unusual among Modern Hebrew writers and artists. Many of the most prominent practitioners of Modern Hebrew literature wrote for children as well as for adults. The list includes Hayim Nahman Bialik, widely considered the first great Modern Hebrew poet; Rahel Bluwstein, the founding mother of Modern Hebrew poetry; and Nathan Alterman, the enormously influential Zionist poet and playwright, to name just a few. Even today, internationally renowned authors such as David Grossman write popular young-adult novels along with their more mature novels. In the visual arts, children’s books in Israel regularly feature illustrations by esteemed painters, designers, and newspaper cartoonists. As members of a young, ideologically driven country, Modern Hebrew writers and artists have seen work for children as part of their national and cultural obligation, and many prominent practitioners have moved between adult and child audiences (Shavit).

But unlike art forms such as painting, theater, dance, and literature, which flourished in the new State of Israel, Hebrew comics remained compartmentalized in audience and in ambition for the first forty years of their existence. Artists such as Navon and Goldberg saw their work in comics partly as an economic sideline, and partly as a minor contribution to Zionist identity and Hebrew language. Comics remained an extremely small field, occupying a couple of pages in issues of children’s magazines, not sold as stand-alone periodicals as they were in the United States. In the late 1940s, when one in three periodicals in the United States was a comic book, Israelis had the back page of Davar li-yeledim, and little else.

Like the larger Israeli arts and literature scene, cartooning was dominated by men in the pre-State years and in the early days of the State of Israel. But a number of important female artists and writers were able to overcome this dominance and play leading roles in the development of Israeli culture. Perhaps this was because Israeli culture was being invented moment by moment, with few calcified institutions or long-standing practices; or because new talented writers and artists were arriving in the country all the time, constantly changing the talent pool; or perhaps it was because of the emphasis on equality embodied by the socialist kibbutz movement (to whatever extent it was realized in actuality). In any case, the early years of Israeli comics, like other Israeli art forms, were never a boys-only club. For those looking for foremothers of Israeli comics, three names stand out: Leah Goldberg, Friedel Stern, and Elisheva Nadel.

Before Rutu Modan, the most significant woman to write comics in Israel was Leah Goldberg, one of the aforementioned creators of Uri Muri. Goldberg’s work in comics is just a small part of her oeuvre. Her remarkably diverse career includes numerous books of poetry that are considered classics of Modern Hebrew; books for children that are still found on the shelves of many Israeli homes; translations into Hebrew of literary giants such as Tolstoy, Rilke, Shakespeare, and Chekhov; novels; plays; and a long tenure as a book and newspaper editor for leading Israeli periodicals and publishers. Her prolific career lasted until her death at the relatively young age of fifty-nine. As someone who played multiple roles in the arts and writing scene of her day, Goldberg is an important predecessor to Modan. Forty-seven years after her death, Goldberg retains a core place in Israeli culture. Her children’s poems are read in preschools and included in high school exams, and her face appears on the recently redesigned Israeli 100 shekel bill. Goldberg’s poetry overshadows her comics, but for decades she created the rhymes that narrated the stories of Uri Muri, Uri Cadduri, and numerous other well-known comics characters. She wrote in a witty but rigorous Hebrew, even for one-page comic strips. Because of her continuing cultural resonance and rich legacy in comics, Modan turned to Goldberg’s work as source material in 2013 when she began Noah Books, an imprint focused on comics for children. (Noah Books, Goldberg’s rhymes, and Modan’s interpretations of her work will be discussed in chap. 6.)

While Goldberg provided the words for early Hebrew comics, Friedel Stern and Elisheva Nadel helped to shape the visual legacy of Israeli comics and cartooning. Rutu Modan does not cite these artists as direct influences (when she began drawing comics, as an adult, she was attracted to much more sophisticated European artists). But along with Goldberg, these women helped to establish a role for women in Israeli comics and illustration and as such are part of the larger tradition to which Modan belongs.

Friedel Stern is the best-known female Israeli cartoonist. Born in Leipzig, Germany, in 1917, she immigrated to Palestine in 1936 to escape Nazi anti-Semitism. As Modan would many years later, Stern studied in Jerusalem at the Bezalel Art School (later the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design), which in the 1930s became a destination for many German Jewish refugee artists fleeing the Nazis. Stern grew to be the most prominent (and often the only) woman cartoonist working in Israel over her remarkably varied seventy-year career. Always a freelancer (unlike her male counterparts, who were hired for salaried jobs at the same newspapers for which Stern freelanced), she drew editorial cartoons, magazine illustrations, posters, advertisements, comics for children’s magazines, and other work that put her in front of Israeli audiences nearly every day. Her popular book Israel in Fourteen Pictorial Maps, published in the 1950s, is a hybrid work far ahead of its time (Katz). Combining maps of the country with cartoon characters and historical and demographic information, the book is now considered one of the classic depictions of the new State of Israel.

Stern drew in a minimalist style, using a single elegant line. Her style is similar to that of many cartoonists of her era, particularly the prominent group of male cartoonists that included Ephraim Kishon, Yaakov Farkash (Ze’ev), Kariel Gardosh (Dosh), and Yosef Lapid (who were collectively known as the Hungarian Mob, because of their shared Hungarian backgrounds). Because of her strong association with cartoonists of her generation, Stern’s individualism as an artist has sometimes been obscured. She remains strongly linked with classic Zionist values, so much so that she has been referred to as the “woman who drew the Zionist Project” (Anderman, “Ode to a Woman”). But much more than other cartoonists of her time, Stern’s drawings acknowledged and represented people marginalized by the early days of Zionism. Alone among her fellow cartoonists, she drew cartoons from the point of view of Israeli women and their particular struggles in Israeli society. Her cartoons also explore the ethnic identities of Jewish immigrants to Israel and the challenges of immigration and assimilation. Her critical distance (and occasional sense of alienation) from her country is reflected in the title of the Israeli Cartoon Museum’s 2012 retrospective exhibition of her work: Hayiti tayeret be-aretz (I was a tourist in the land of Israel).

Although their illustration styles have little in common, Stern and Modan share a willingness to criticize Israeli society and an interest in the experience of Israeli women. (It is worth noting that, unlike Modan, Stern’s interest in the marginalized does not really extend to the Palestinians.) And Stern’s experiments in combining text and image, as shown in Hayiti tayeret be-aretz, provide an intriguing antecedent to the books Modan would later create as part of Actus comics and then on her own.

A more direct visual predecessor to Modan, in terms of bringing a sophisticated approach to narrative comics, is Elisheva Nadel, who signed her work with the single name Elisheva. Unlike Friedel Stern, a public figure in Israel who gave interviews until her death at ninety, little is known about Nadel’s personal life. She is known best for drawing the popular comics character Gidi Gezer (Carrot-Top Gidi), who appeared first in the early 1950s in the children’s magazine Haaretz shelanu. (Like Davar li-yeledim, Haaretz shelanu was an offshoot of a popular daily newspaper.) Gidi, a red-haired teenager, enjoyed a series of Zionist adventures beginning in the British Mandate era and moving through the War of Independence (1948–49) and the Sinai Campaign (1956). Though never referred to as a gibor-al (superhero), Gidi displays characteristics of classic superheroes. Gidi becomes super-powerful by eating his signature carrots. These powers aid him in fighting British soldiers in the Yishuv and Egyptians in the Sinai, in spying on Arab troops, and in defending the Jewish state from other enemies (fig. 1.1). In many ways, Gidi is a standard Zionist “New Jew”—a brave Jewish boy who is clever and strong. But not all of Gidi’s adventures are militaristic, and some show a sympathetic attitude toward the Palestinians, even in times of violence. In one notable strip from the 1950s, illustrated by Nadel and written by Jacob Ashman, Gidi sneaks into Gaza to locate an Arab shopkeeper during a time of military conflict in the nearby Sinai Peninsula. The outbreak of violence has prevented Gidi’s father from repaying a debt he owes to the shopkeeper. Gidi finds the merchant and absolves the debt himself, maintaining the good relationship between his father and the shopkeeper even in a time of war (Farber 61).

Nadel worked with a number of different writers over the course of her career, most notably the novelist and poet Pinhas Sadeh, who wrote children’s comics under a ...