1

DEFENSE

The trimmed-down argument stresses the interdependence of war making and state making and the analogy between both of those processes and what, when less successful and smaller in scale, we call organised crime. War makes states, I shall claim. Banditry, piracy, gangland rivalry, policing, and war making all belong on the same continuum—that I should argue as well.

—Charles Tilly, 1985

Ki jan ou ye? M ap goumen! (How are you? I keep fighting!)

—Popular greeting in Bel Air

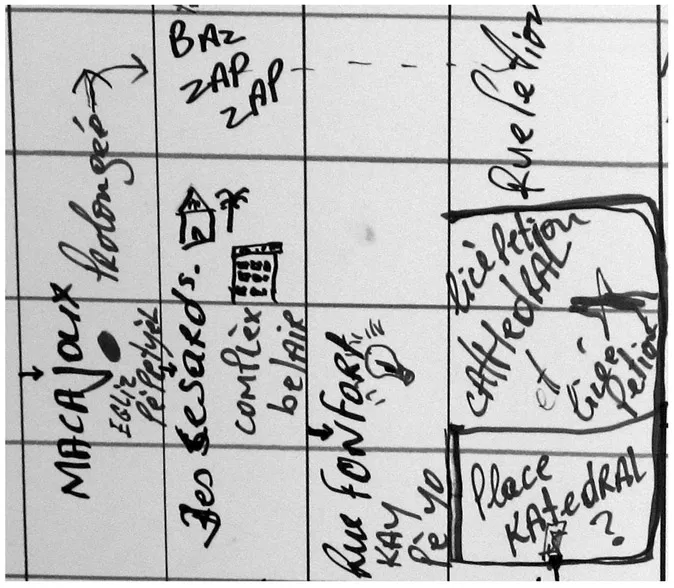

In ostensibly familiar ethnographic fashion, I began this ethnography with cartography.1 That map situated my field-site within the city of Port-au-Prince and the country of Haiti. Here I turn to a different kind of map—one that captures both the emplacement of the baz in the neighborhood and how the baz organizes sociality and security for Bel Air residents. Drawn for me by five members of Baz Zap Zap at the start of fieldwork in 2008, this map also serves as an artifact of residents’ initial efforts to render their neighborhood legible to me.

In a neighborhood school, on a warm November Saturday, I laid a piece of poster board on an unsteady desk and handed out a collection of markers, which soon ended up in the hands of Frantzy and Michel, the most formally educated and, as such, steady of hand. Per convention, they began with a neat and tidy street grid. But once the map was complete, they realized the rigid black-and-white lines would not work. Part of the problem was that the majority of residents did not dwell streetside but in the vast labyrinth of back alleys and corridors that cut across the area’s dirt hilltops. But even more problematic was that the grid did not include the most critical geography in Bel Air. They quickly located a box on the grid and labeled it “Baz Zap Zap.” From there, they identified other significant landmarks, including local schools, churches, and, of course, other baz. Most significantly, they marked the major crossroads adjacent to their baz with a bold red dot, indicating it as a cho (hot or dangerous) area. It is there that stands L’église de Notre Dame du Perpétual de Secours, the bullet-ridden Catholic church in front of which many city protests begin and where, in turn, most confrontations between residents and police and peacekeepers occur. It is also the location of the baz formation with which Baz Zap Zap is locked in competition, at times respectful, at others hostile. At this time, this rival baz, called Grand Black, was in a conflict with another nearby baz known by its Carnival group Samba the Best, which is why it was identified on the map. The dispute involved the handling of Carnival funds, and by this point, death threats had been exchanged. “There’s too much ensekirite. The things have become cho. Between them, you won’t hear ‘my baz’!” Michel jokingly remarked when darkening the red dot. His comment underscored how the baz demarcates social affiliations and attachments against the complex of social threats known in Haiti as ensekirite.

FIGURE 5. Map of Bel Air drawn by members of Baz Zap Zap.

A primary aim of this chapter is to make sense of the connection between that red splotch on the map and what may be called, following Pierre Bourdieu, the baz’s defensive “habitus,” the set of “durable, transposable dispositions, structured structures predisposed to function as structuring structures, that is, as principles that generate and organize practices and representations” (Bourdieu 1992, 53). The red dot highlights the many ways in which the baz is indicative of and in dynamic tension with ensekirite. The dot marked physical violence but also the physical burdened by the structural. The mapmakers, for example, thought it important to place a light bulb at the church, the only neighborhood space with twenty-four-hour electricity. The lone light cast the rest of the zone in a blanket of darkness and potential danger. “Blakawout (blackout) makes violence increase,” Kal remarked, as Frantzy drew the bulb. An interesting choice of words, a blackout suggests not merely darkness but darkness where there should be light. With it, the mapmakers invoked a sense of danger tied to the physical and social obscurity of living with informal and rarely functioning electricity. Yet as much as the mapmakers framed the neighborhood as beyond city services, they also situated it at the center of city life. They identified the National Palace, Grand Rue (the city’s main commercial road), Mache Tèt Bèf (the historic market), and the National Cathedral, among other landmarks. It is Bel Air’s liminal position as politically central yet socially peripheral that staged the drama of the baz project. It raised the possibilities and the problems, the fortunes and frustrations of attempting to protect and advocate for the neighborhood from a marginal sociopolitical slot, a place within yet beyond the heart of the state.

The New Insecurity

In the popular US imaginary, Haiti conjures not only a very poor but also a very dangerous place. In addition to perpetual travel warnings listing the risk of theft, murder, and kidnapping of US citizens, Haiti (along with countries such as Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria) was listed as an “imminent danger area” by the US Department of Defense until 2014. For Bel Air and other poor urban districts, the United States and Canada have special regional advisories, which strongly advise travelers to avoid them due to the prevalence of “armed gangs.” In 2004–2006, Bel Air baz waged an armed resistance against the forces that ousted Jean-Bertrand Aristide from the presidency. Since Baghdad, as this period is called, the UN has designated Bel Air a “red zone.”2 The classification barred diplomatic and aid staff from entering the area unless under military escort. During my research, police and peacekeepers routinely patrolled the neighborhood and manned checkpoints surrounding its borders, allowing residents in and diverting other traffic. Such labels and barricades enforced a high degree of “inner-city apartheid” (Bourgois 1995, 32), cordoning off the neighborhood as a zone de nonendroit (no-go zone), a place where outsiders are afraid to enter and residents are unable to get out. Most foreigners in Haiti were bewildered at my decision to frequent the area on a daily basis, seemingly convinced that I would be robbed, kidnapped, or otherwise victimized by gangs savagely roaming the streets. Many of my middle-class Haitian friends shared their concern and have refused, for some time now, to travel farther downtown than the borderlands that mark entry into the Bel Air and Delmas 2 neighborhoods.

These perceptions stigmatized residents of these areas, while at the same time obscuring the burden of risk faced by them. The censorious North American and UN labels, in particular, overstate the risk to foreigners, especially white foreigners, who often benefit from racial and national privilege. I was reminded of this when security agents at checkpoints appeared overly concerned with my safety, instructing me to “make a quick visit” and “leave before dark.” My friends in Bel Air also reminded me of the heightened level of protection I enjoyed. On my early trips to Bel Air in 2008, Berman, a late friend of Kal’s, often informed me that my security was assured because most likely people assumed that I was connected to the Embassy, “the biggest baz of all!” Kal, attuned to the global media landscape, grasped my privilege in allied terms: “No one can do anything to you because if anything happened it’d be on CNN in no time!” he often joked.3 In fact, during all the time I spent in Bel Air, walking around during the day and at night, and eventually living there for six months, I was never assaulted.4 But this is not to say that violence was not a fact of life for Belairians. Indeed, in this same span of time, Kal’s house was robbed twice, his motorbike vandalized, his estranged daughter raped, his face slashed with a razor, and his left eyelid split open from a fight. If this weren’t enough, three of his good friends were killed, two in gun violence and one in the earthquake.

While the urban poor have long lived precarious lives, Kal’s experience reflected an intensification of ensekirite induced by new forms of violence closely linked to baz formations.5 Invoking US idioms, this violence is often glossed in official and lay accounts as gang violence—with crime and policy reports citing afwontman antre gang (gang confrontations) and aksyon gang (gang actions) for the muggings, carjackings, and kidnappings that have swept the country since the early 1990s.6 The label of gang violence can mislead one into thinking that this violence is tied to criminal, rather than political, economies. For one, much of the so-called gang violence has been explicitly political. During Baghdad, rates of criminal violence skyrocketed in large part because some baz resorted to kidnapping and theft (usually targeting residents of neighboring geto) in order to acquire the weapons and ammunition they needed to wage daily battles with police and peacekeepers. Second, the economy of the baz has not revolved around the drug trade but rather the trade in political and development goods and services. The majority of baz conflicts I witnessed stemmed from disputes over access to or distribution of political funds and resources. Third, political instability and governmental neglect have provided a platform for criminal violence to flourish, affording the license (righteous cause) as well as the cover (widespread disorder) that have driven individuals to exploit and injure their neighbors in pursuit of wealth and power. “The majority of soldiers deviate from the battle,” lamented a popular rap song about Baghdad; another commented on the rise of petty thievery during elections and warned, “When there’s campaigning, don’t leave your sneakers out to dry!” Many baz began—and still act—as brigad vijilans that protect against such broad and interconnected forms of ensekirite.

The Creole term ensekirite that Bel Air residents used to refer to the threat of violence in their lives identified more than an elevated crime rate. It marked an overarching sense of vulnerability. Neither entirely one’s own nor entirely outside of oneself, ensekirite articulated, as the anthropologist Erica James put it, an “embodied uncertainty” (2010, 8). It reflected an epistemology of violence premised on the seamless integration of a range of threats. Insecurity could imply being under personal attack, whether waged by physical force, verbal threat, or sorcerous spell. It could also suggest the presence of impersonal, communal hazards, such as those that dwell in the environment beyond one’s control, like the threat of being caught in the crossfire of another’s battle or in the mayhem of a political protest when going about daily errands. Insecurity could further imply the menace of poverty. The greatest worry for Bel Air residents often stemmed from the most ordinary of exigencies: fear of a nighttime fire from rigged electrical connections, eviction from squatted housing, and the constant threat of hunger. As James, quoting a Belgian priest and social activist based in Port-au-Prince, wrote, “In Haiti, misery is a violence” (2010, 7). The phrase rang true not only because misery produced its own wounds, but also because efforts to circumvent it drove an ethos of defensive positioning and social brinkmanship that multiplied violence.

When asked what they do, baz leaders usually responded, “We defend the zone!” or “We defend our people!” As a result, a pivotal term for my analysis here is defend, or in Creole defann. The term defann comes from the French défendre, via the Latin roots de, meaning “away from,” and fend, meaning “to strike.” In Creole, as in colloquial English, notions of defense usually refer to the acts of “fighting off” or “protecting against” harmful persons, animals, or things. But, as in legal discourse, the notion of defense can also refer to the act of “coming to the aid of” an ally at risk or in danger. In phrases like “We defend the zone,” baz leaders drew on both meanings of defense, asserting that they not only protected the zone against outside threats but also advocated for its needs and desires. In this sense, their defensive project was aimed at mitigating the twofold situation of insecurity represented by the red dot—that is, both social conflicts and exacting sociopolitical realities. In bringing these two dimensions together, the notion of ensekirite, I argue, can undo a false dichotomy between social violence and what scholars have called “structural violence,” or the violence resulting from the unequal ordering of persons in society (Galtung 1969; Farmer 1996, 2004). In particular, ensekirite, with its multivalent connotations, can provide a rich analytical tool for exploring how multiple forms, scales, and temporalities of violence intertwine in the production of vulnerability. By speaking of ensekirite, I aim to show how acts of violence spiral into each other in ways that resist categorical, scalar, or temporal partition.7 Baz leaders saw themselves as simultaneously defending against an ensekirite that was physical and structural, interpersonal and societal, and episodic and durational. In what follows, I show the inventive and often productive strategies used by the baz to defend against manifold threats. However, I also show how their efforts to defend the zone propagated new vulnerabilities. What was often not captured in leaders’ claims to defend the zone, but readily apparent in their actual attempts to do so, was how their efforts to protect against threats or advocate for much-needed resources all too often incited rivalries and conflicts that put themselves and their neighbors at risk—as I trace in the following snapshot of a day in Bel Air that was cross-cut by multiple and entwining vectors of ensekirite.

Defense I: A Day against the World

In December 2012, I began a monthlong stay in the two-room shack where Kal, his wife, Sophie, and their teenage daughter have squatted since the earthquake in 2010. Kal was born in 1980 in a Bel Air house rented by his mother, a seam-stress, and father, a low-ranking soldier in the Haitian army. But, at thirteen, after his mother died of tuberculosis, his father left the area, and he began staying at a friend’s house. Handsome, musically inclined, and politically connected, he was able to overcome his meager financial situation and court several women. In 1998, at age eighteen, he had two women pregnant at the same time, ultimately committing to Sophie because she was, in his words, a “good woman” (bon fi), and because she took him into the house she shared with her sister. Ever since I met Kal in 2008, his goal was to have a job and his own house. With this, he said, he could “fè (become) the man.” In 2010, at age thirty, Kal achieved the second half of this goal by capitalizing on the destruction of the earthquake.

He built his house on a sliver of land left unoccupied after a family, whose house collapsed in the tremors, left for the Dominican Republic. Using plywood, tarps, and Styrofoam, which the baz leader Yves had attained as a result of his engagement with the government’s postearthquake relocation committee, Kal constructed a two-room shack on the salvaged concrete platform. A six-by-six-foot front room served as a kitchen, bathing area, and nightly motorbike garage. We all slept in the slightly larger backroom, with Kal and Sophie on the concrete floor and their daughter, Laloz, and me treated to a lumpy mattress stacked atop clothes and other belongings. A small freezer, defunct television, and wooden hutch consumed the space, and Sophie had to stack the items to make room to sleep. Each night, she removed from atop the hutch an impressive collection of trinkets and baubles, from Precious Moments porcelain angels to plastic Arthur and Mickey Mouse dolls to faux flowers; and each morning, she carefully rearranged them. “You can live in a little house,” she often remarked as she performed the ritual, “but that doesn’t mean you can’t make it nice.”

Despite her efforts, Sophie could not stop a myriad of hazards from impinging on her quaint living quarters. Most urgently, a spate of armed robberies had targeted the young men who make small change ferrying people around on their motorbikes in the city. The thefts of cell phones, cash, and motorbikes were largely blamed on a new group of youthful bandits known as Baz 117 and based in the Delmas 2 area adjacent to Bel Air. As a safety measure, some motochauffeurs, including Kal, limited their routes, and others stopped working altogether. This diminished their livelihood but did little to remove the threat, as Baz 117 had taken to exploiting the new routes as well as mounting the zone to steal the motorbikes. When I arrived that December, the first news I heard from Kal was about the ti kouri (little runs) Baz 117 was causing—moments of panic when a sightin...