KRISTOPHER A. KILIAN*a

5.1 INTRODUCTION

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a highly complex composite material, with hierarchical organization, many different organic and inorganic features, and dynamic self-assembly and disassembly processes that regulate tissue homeostasis and morphogenesis. The ECM differs significantly across tissue types, where the mechanical, topographical, biochemical and transport properties of the materials are dictated in a contextual fashion to guide specific cellular and tissue level functions. The presentation of these cues to cells is not a static process, but rather a dynamic interplay between individual cells, their neighbors and the ECM architecture. This spatiotemporal control of signaling patterns in the cellular microenvironment regulates diverse functions, including quiescence, migration, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. Understanding how the properties of the ECM directs tissue form and function is important for fundamental biology research but also for establishing design criteria for next generation biomaterials that aim to recapitulate the structure and function of native extracellular matrices.

Mammalian cell culture is most often performed on rigid tissue culture plastic, where the surface is either pre-coated with defined ECM proteins or coated in situ via the physisorption of biomolecule components in the cell culture media. Both of these processes invariably lead to a heterogeneous deposition of physisorbed matrix components across the substrate. The composition of the initial coating can be defined to reflect aspects of the cultured cells’ natural matrix; however, physisorption to rigid hydrophobic interfaces can cause denaturation of proteins and burying of adhesion cues, and the final surface composition is subject to competition from a large number of proteins in the media with different affinity for the substrate. Furthermore, most cell types will actively remodel their underlying ECM over time through secretion of matrix proteins and protease enzymes. Thus, ensuring that the cell culture surface presents a defined combination of matrix proteins to adherent cells is difficult at best and impossible over prolonged culture. This is important because a defined substrate that reflects the native composition of the microenvironment may be critical for many cell biology studies. In addition, there is considerable evidence that transferring a cell from the native in vivo environment to in vitro culture can lead to phenotypic changes that often result in senescence, differentiation, chromatin abnormalities and death.

In addition to the need for a defined ECM during cell culture, materials for implants, cell delivery formulations for regenerative medicine, and tissue engineering scaffolds require interfaces that promote the desired cellular processes and outcome. For instance, there are significant efforts to modify bone implant materials with bioactive ceramics, matrix proteins and morphogens that enhance osseointegration,1,2 and to fabricate hydrogel materials that recapitulate the architecture and composition of hyaline cartilage.3 Virtually every tissue presents a unique combination of matrix proteins and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) that are assembled in a defined way to influence cell attachment, tissue mechanical properties, and diffusion and sequestration of growth factors; the organization of these components is dynamic, context dependent and ultimately critical to maintaining normal physiology.

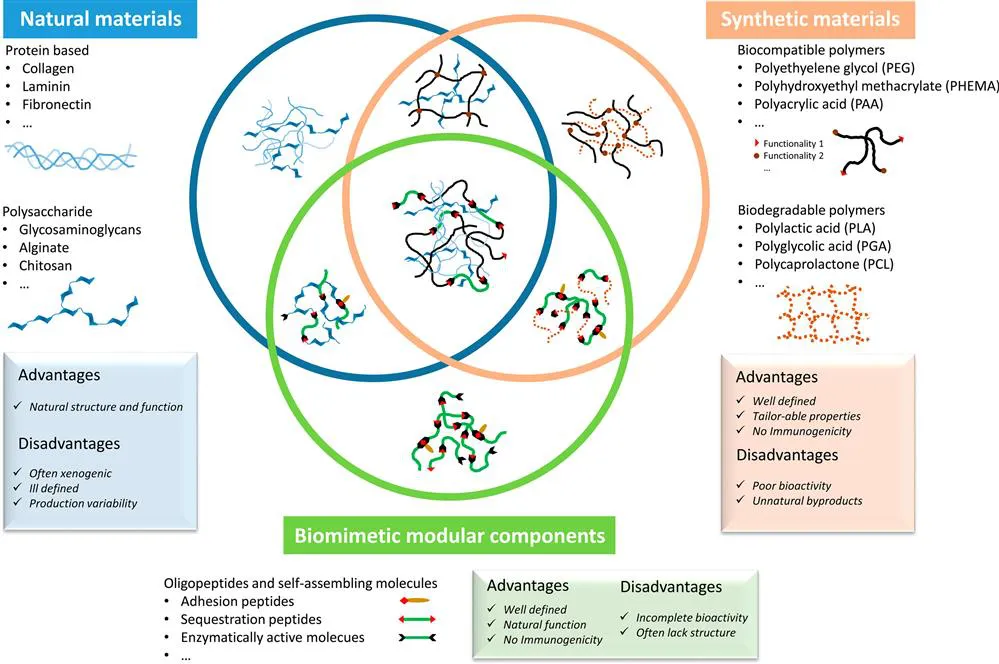

In this chapter we explore the past, current and future prospects for integrating ECM-derived molecular features into biomaterials. Our primary objective is to describe the state of the art in modifying 2D and 3D materials with molecules derived from, or that mimic, the native ECM. Other important parameters including mechanical properties, cell adhesion mechanisms, sequestration of soluble factors, gradient formation, turnover and hierarchical organization will be the subject of later chapters. First we discuss efforts aimed at using natural components—derived from tissues or created through recombinant DNA techniques—to modify biomaterials. Next we focus on methodologies that incorporate small synthetic ECM fragments into biomaterials. Throughout the chapter we explore the future of integrating aspects of these approaches towards leveraging the optimal features of each for the design of ECM-mimetic biomaterials (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Overview of common approaches to incorporate ECM-derived molecules into biomaterials.

5.2 INCORPORATING NATURAL MOLECULES INTO BIOMATERIALS

When designing a 2D cell culture platform, implant or particle coating, or 3D scaffold material, often the most optimal strategy is to use the same molecules present in the host tissue. Natural biomaterials have the advantage of inherent biocompatibility and the potential to present many bioactive features by virtue of having a complete primary structure. Using natural materials from the ECM preserves many physio-chemical features of native tissue with structural and biochemical aspects that promote new tissue development. Some disadvantages associated with using natural materials are limitations associated with production, immunogenicity from xenogenic materials and ill-defined structure and composition. In this section we will discuss the most common approaches to integrate natural molecules into biomaterials with a primary focus on ECM-derived proteins and polysaccharides. The inclusion of soluble factors, important considerations for both natural and synthetic biomaterials, will not be discussed here.

5.2.1 Bioconjugation of Polypeptides and Polysaccharides to Materials

The surface of proteins and polysaccharide are rich with functional groups that are amenable to covalent immobilization to synthetic biomaterials. Of the 20 amino acids, nearly half of these can be conjugated using simple methods under physiological conditions that preserve biomolecule structure and function.4 Important considerations when developing a method to conjugate a biomolecule to a surface includes solvent accessibility of the functional group and relative nucleophilicity. Of particular note are amino acids with ionizable side chains—aspartic acid, glutamic acid, lysine, arginine, cysteine, histidine, serine, threonine and tyrosine—where in the unprotonated state these side chains can act as potent nucleophiles for addition-type bioconjugation reactions (Figure 5.2a). Similarly, many polysaccharides have accessible functional groups for derivatization; in particular, free hydroxyl groups, carboxylic acids and amines appear in many ECM components (Figure 5.2b).

Figure 5.2 Bioconjugation approaches for modifying biomaterials. (a) Amino acids used in modifying biomaterials or linking protein-based and/or polysaccharide-based biomaterials. Right: common bioconjugation reactions often employed in biomaterials science. (b) Polysaccharides that are often used in modifying biomaterials; functional groups for bioconjugation are highlighted. (c) Surface modification schemes for incorporating distal reactivity for bioconjugation through routes depicted in (a) and (b).

In order to immobilize the biomolecule, the surface of biomaterials often needs to be derivatized to present a complementary chemistry. Strategies to functionalize a surface largely depend on the type of material, and many different strategies have been developed over the years. Of particular note, plasma treatment can be used to change both the physical and chemical properties of a surface to modify the way in which it integrates with biological systems. For instance, oxygen plasma can be used to introduce hydroxyl and carboxylic acid groups onto the surface of many materials, including ceramics, metals and polymers.5 This treatment ...