- 150 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Recycling of Polyurethane Wastes

About this book

This book investigates processes to reduce environmental pollution and polyurethane (PU) waste going to landfill. The author explains recycling approaches as well as instrumental methods such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and Fourier-Transform infrared spectroscopy for characterization and identification of PU recycling products.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Recycling of Polyurethane Wastes by Mir Mohammad Alavi Nikje in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

1.1 Introduction to polyurethanes

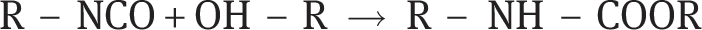

The German chemist Otto Bayer invented polyurethane (PU) in the 1930s as part of his research on polymer fibres. PU is produced by reacting a polyether or polyester polyol as a hydroxyl-containing monomer (a polymeric alcohol with more than two reactive hydroxyl groups per molecule), such as polypropylene glycol or polytetramethylene glycol, with diisocyanate or a polymeric isocyanate [e.g., 4,4′-diphenylmethane diisocyanate (MDI) or toluene diisocyanate (TDI)] in the presence of suitable catalysts and additives, especially chain extenders (e.g., 1,4-butanediol (1,4-BD) [1, 2]) as shown in Equation 1.1:

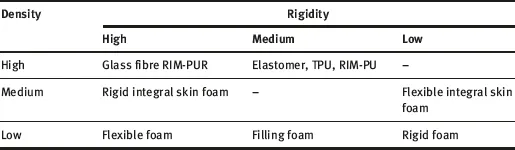

With a wide range of high-performance properties, PU are essential for a multitude of end-use applications. PU represent an important class of polymers that have found widespread use in medical, automotive and industrial fields, and are one of the most important classes of polymeric materials within the plastics ‘family’. Due to the wide versatility of the materials, PU is around us in many products we use every day. For example, it can be found in liquid form in coatings and paints, and in the solid state as elastomers, rigid insulation for buildings, soft flexible foam in mattresses and automotive seats, or as an integral ‘skin’ in sports goods such as skis, surfboards and automotive parts. Obviously, because of the large variety of starting materials (i.e., polyols and isocyanates), this family would exhibit various organic chemical behaviours. By considering endless chemical-processing routes of the reacting chemicals, numerous various materials may be synthesised that would fall under the definition of PU. Besides urethane linkages, PU structure may be defined by ether, urea, and amide functional groups. As a result, PU stands for a product range or plastics-industry segment rather than for a single, well-defined polymer resin (e.g., polyvinyl chloride). The range of applications of the various PU materials is extensive. A simple classification of PU-based products is given in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Classification of PU-based products according to density and rigidity.

RIM: Reaction injection moulding

TPU: Thermoplastic polyurethane

Reproduced with permission from M.M. Alavi Nikje,

A. Bagheri Garmarudi and A.B Idris, Designed Monomers and Polymers, 2011, 14, 5, 395. ©2011, Taylor & Francis [1]

As shown in the Table 1.1, rigid and flexible PU foams (PUF) are produced in large quantities and consumed in various industries. The ratio of application of rigid to flexible foam is ≈1:3. PUF are defined depending on whether the cell structure is ‘open’ or ‘closed’.

In rigid PUF, a low percentage of cells have an open-cell structure, and the bulk density of these products is ≈30–35 kg/m3. The physical blowing agent as the gas contained within the cells results in very low thermal conductivity, and the main use of rigid PUF is in the insulating panels of refrigerators. Flexible PUF have a virtually completely open-cell structure with typical densities of 20–45 kg/m3. Therefore, they are not useful as insulators and are often used in the production of seats and furniture [1].

During recent decades, chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) such as CFC-11 (CCl3F) have been used widely as physical blowing agents because they are non-toxic, non-flammable, stable, inexpensive, very soluble in isocyanate and polyols but not in the PU, and give excellent thermal insulation [2]. However, they have ozone-depleting potential and are not environmentally friendly. To overcome these drawbacks, organic liquids with low boiling points have been found to be useful physical blowing agents in foam production, with the additional benefit (discovered when developing rigid PUF) of improving the insulating properties of the final product. PUF production is relatively straightforward. It can be accomplished by adding water as the chemical blowing agent, which results in the release of carbon dioxide as the reaction product of water and isocyanate, and more urea [–(NH–CO–NH)–] linkages in the polymer chain. However, using water alone as the blowing agent would not result in satisfactory quality or durability of the product for many applications.

1.2 Chemistry of polyurethanes

PU are a broad class of polymers that contain the urethane (–NH-CO-O–) linkage or functional groups in the polymer backbone. They are formed by the reaction of an isocyanate containing two or more isocyanate groups per molecule [R-(N=C=O)n, n ≥2] with a polyol containing on average of two or more hydroxyl groups per molecule [R′-(OH)n, n ≥2] in the presence of a catalyst and other additives via a well-known gel reaction [2].

1.2.1 Isocyanates

Isocyanates are essential components required for PU production that must have two or more isocyanate groups on each molecule. The most important and common aromatic isocyanates in the PU industry are TDI and MDI, respectively. Industrially, TDI is formed by the phosgenation of diaminotoluene – which is synthesised by the reduction of nitrotoluene – as a mixture of the 2,4- and 2,6-TDI isomers (80/20 TDI). In the same reaction pathway, MDI is formed by the phosgenation of the condensation product of aniline and formaldehyde [3]. In the meantime, the easy availability and low costs of TDI and MDI isocyanates precursors resulted in these isocyanates having the greatest role and consumptions in the PU industry. Industrial grades of TDI and MDI comprising mixtures of isomers often contain polymeric materials. They are used to make flexible foam (e.g., slabstock foam for mattresses or moulded foams for car seats), rigid foam (e.g., insulating foam in refrigerators), and elastomers (e.g., shoe soles). Isocyanates can be modified by partial reactions with polyols or by introduction of other functional groups to reduce volatility and toxicity. These strategies decrease their freezing points to make handling easier or to improve the properties of the final products. The choice of the isocyanate for PU synthesis is governed by the properties required for end-use applications. For the manufacture of rigid PU, aromatic isocyanates are chosen, and PU derived from these isocyanates demonstrate lower oxidative and ultraviolet (UV) stabilities. The other main groups of isocyanates are aliphatic and cycloaliphatic. They are used in limited volumes, most often in coatings and other applications where colour and transparency are important because PU made with aromatic isocyanates tend to darken upon exposure to light. The most important aliphatic and cycloaliphatic isocyanates are 1,6-hexamethylene diisocyanate (HDI), isophorone diisocyanate (IPDI), and 4,4′-diisocyanato dicyclohexylmethane (H12MDI). IPDI is used widely in the preparation of light-stable PU coatings. For a brief review of the chemical structures of common isocyanates, see Figure 1.1 .

1.2.2 Polyols

The other component in PU formation is a polyol. The chemical structure of these compounds has a profound effect on the properties of the final PU polymers. These compounds have a hydroxyl group that can react with diisocyanate, which enables preparation of various types of PU. Structurally, polyols are divided into two main categories: polyether polyols (manufactured by the reaction of an epoxy functional group-containing starting material with a reactive hydrogen-containing starter or initiator) and polyester polyols (made by the polycondensation reaction of two and/or multifunctional carboxylic acids and polyhydroxyl compounds or alcohols). Polyols can be classified further according to their end use. Polyester polyols consist of ester and hydroxylic groups in one backbone. For example, polycaprolactones (PCL) are polyester polyols produced by ring-opening polymerisation of a caprolactone monomer with a glycol such as diethylene glycol (DEG) or ethylene glycol (EG) and other diols and triols. The wide variety in PU applications refers to the molecular weight (Mw) of the polyol, polyol type, crosslink densities, and isocyanate type. In this case, higher-Mw polyols varying from 2,000 to 10,000 are used for the formulation of more flexible PU, whereas lower-Mw polyols make more rigid products. Monomeric polyols such as glycerin, pentaerythritol (PER), EG and sucrose often serve as the starting materials or initiators for preparation of polymeric polyols.

Flexible PUF comprise polyols with low-functionality (f) initiators such as dipropylene glycol (f = 2), glycerine (f = 3) or a sorbitol/ water mixture solution (f = 2.75). Polyols for rigid applications use high-functionality initiators such as sucrose (f = 8), sorbitol (f = 6), toluenediamine (f = 4), and Mannich bases (f = 4). For preparation of all polyether polyols of these categories, propylene oxide (PO)- and/or other epoxy functional group-containing compounds and a mixture of these starting materials are added to initiators until the desired Mw is achieved. The order of addition and the amounts of each epoxy functional group-containing starting material affect the properties of the polyol, such as compatibility, water solubility, and reactivity. For example, polyols prepared with only PO are terminated by...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Brief review of the methods of recycling of polyurethane foam wastes

- 3 Chemical recycling of flexible and semi-flexible polyurethane foams

- 4 Chemical recycling of rigid polyurethane foams via thermal and microwave-assisted methods

- Abbreviations

- Index