![]()

1

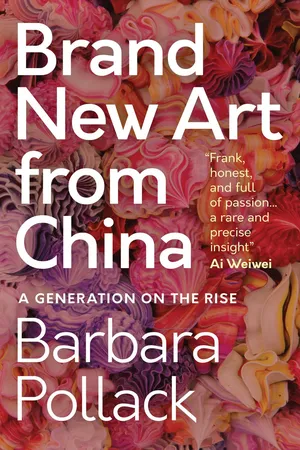

THE LAST CHINESE ARTISTS

Any assessment of the new generation of artists emerging in China must first begin with an overview of the generation that came before them, those who emerged in the late 1980s and 1990s. They were among the first artists to begin careers after the Cultural Revolution, the first to have exhibitions in China, the first to be acknowledged abroad, and the first to make records at the world’s auction houses. In their capacity as ambassadors for a post-Communist yet still relatively isolated and remote country, they carried the burden of explaining China to the rest of the world. And for this reason, among others, their artworks were viewed through the prism of Chinese identity whose artistic merits played second fiddle to their role as guideposts to a new China.

Known for his solemn portraits of Chinese families, Zhang Xiaogang is an artist who has broken all auction records but remains humble and reticent when talking about his life. Born in 1958 and raised in Sichuan Province, he has experienced the upheavals in China over the last six decades, from the Cultural Revolution to its current booming art market. Yet, when he speaks about his paintings, he always talks about them as very personal memories, despite the fact that they have been widely interpreted as political commentary.

Sitting across from him in an elegant room in his Beijing studio, I watch his carefully composed expression as he answers my questions, always considered and considerate without ever quite breaking into a smile. We have known each other a long time, ever since 2007, when he was still chain smoking and drinking as he worked on his canvases late into the night. That was seven years before Bloodline: Big Family No. 3, a 1995 painting that sold for over $12 million at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, a record for Chinese contemporary art. Today, after a recent heart attack, he lives a much more sober life with no cigarettes in sight, and he works at a slower pace due to doctor’s orders. But his success has not ceased, including a 2016 exhibition pairing him with American minimalist artist Sol LeWitt at Pace Beijing, the China outpost of the world-renowned Pace Gallery.

“So much has happened over these past decades that it is hard to summarize in a few words the differences between these two generations,” he begins, when asked to comment on the changes he has observed between his generation and the younger artists that he teaches at the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts. He was a student there himself in the late 1970s in one of the first classes to graduate after the end of the Cultural Revolution.

ZHANG XIAOGANG, BLOODLINE: BIG FAMILY NO. 3, 1995. COURTESY OF PACE GALLERY.

Zhang Xiaogang experienced the injustice of the Cultural Revolution firsthand, as an eight-year-old whose parents were sent away for “re-education,” living with his brothers under the care of an aunt for most of his childhood. Later in 1976, he was sent to the countryside himself, like so many youth, but he had already picked up the habit of drawing, which allowed him to enter the academy after it reopened its doors when the Cultural Revolution ended. His years at school, and following his graduation, were a heady time, exposing him to Western masters from Impressionists to Surrealists, despite the fact that information was still limited and fragmentary.

“Our hopes, aspirations and value systems at the time are clearly not enough for today,” says Zhang. “The knowledge we acquired then seems fairly old now, even though it was really fresh and exciting to us at the time. People were passionate then. Today is the era of information overflow.”

It is almost impossible to comprehend the changes that Zhang Xiaogang is commenting on without a brief overview of Chinese contemporary art history. For while it may seem that he was among the first Chinese artists with exposure to Western art trends, the history goes back much farther and is rich with contradictions. In this context, Zhang’s resolution of Chinese and Western influences, and his success both on the global stage and within China, are all the more remarkable.

The history of Chinese contemporary art is brief in comparison to art histories of the West, beginning as it did in 1976 with the end of the Cultural Revolution. But the struggle to discover a Chinese modernity goes back much further, at least to the May 4th Movement of 1919, which spawned a New Cultural Movement rooted in Western ideas and opposing traditionalist values. While the history of this period is complex and contradictory, leading eventually to the rise of the Communist Party, the artists of that era are best known for widespread experimentation, drawing from Cubism and post-Impressionism in opposition to the ornate craftsmanship and classical scroll paintings of the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Unfortunately, the Communist Revolution of 1949 put an end to much of this free-spirited expression. Under Mao, art was reformed to serve the people through an endless state-controlled production of propaganda and history paintings glorifying happy peasants and heroic soldiers and formal portraits that idealized political leaders. This political kitsch came to a head with the Cultural Revolution, a period from 1966 to 1976 in which all forms of expression came under attack as the remnants of bourgeois society with the potential to undermine the transformation of Chinese society to a Communist regime. The fallout from this period is well documented, including nearly a million deaths and the complete eradication of an intellectual class, with artists and writers regularly sent to the countryside for what was considered re-education. Even when art schools reopened after 1976, students were still taught to mimic the conventions of Socialist Realist painting, a practice that continues to today.

However, by 1985, Chinese artists, like Zhang Xiaogang, had regained much ground during a period of liberalization leading up to the pro-democracy movement at Tiananmen Square. During the ’85 New Wave movement, artists began to smuggle in catalogs from Western art exhibitions and a few prominent artists from the USA and Europe began having shows in China, most notably Robert Rauschenberg and Gilbert & George. Chinese artists leapt on an entire art history kept from them during the Mao era, digesting in one gulp everything from abstract expressionism to Pop Art. This period of experimentation culminated in the landmark China/Avant-Garde exhibition, held in 1989 at the National Gallery of Art, now known as the National Art Museum of China in Beijing. Displaying everything from installation art to performance art, the exhibition had a brief run just months before the crackdown at Tiananmen Square.

By 1990, government censorship forced Chinese artists back underground, but the progress that had been made could not be suppressed. In subsequent years, artists held exhibitions in unofficial places, such as apartments, studios, and empty temples. By the mid-1990s, some of this work had begun to circulate at international art exhibitions outside of China, and Zhang Xiaogang had his first shows abroad. Several leading Chinese artists, such as Cai Guo-Qiang, Xu Bing, Huang Yong Ping, and Zhang Huan, relocated to New York and Paris, finding a warmer reception in foreign cities than in their hometowns.

By the time we come to examine those artists who emerged in the 1990s, such as Zhang Xiaogang and Cai Guo-Qiang, Chinese attitudes towards identity and culture had gone through several transformations and meant many contradictory things. For those artists which remained in China, the questioning of identity was a form of individual expression in opposition to an enforced notion of China imposed by the government during the Cultural Revolution and in the post-Tiananmen era. For government officials whose job was to regulate these artists, Chinese identity was fixed and certain, unquestionably serving political forces that did not tolerate negative portrayals of China. For a new generation of Chinese art critics, “Chinese-ness” was an essential inherited condition, rooted in Confucianism and classical art forms that could be modernized but must remain forever on guard for dilution from Western influences. And for Chinese artists living abroad, Chinese identity was a negotiable state of being, a component of their individuality that could be inserted into a global dialogue.

This variety of ways of expressing identity were not set in stone, and often conflicting ideas could be read into the work of a single artist. For example, Xu Bing made his groundbreaking work Book from the Sky in Beijing in 1988, shortly before leaving China for the USA in 1991. This installation fills a room with scrolls covered in thousands of characters that look like ordinary Chinese, but on closer inspection, turn out to be unique letters invented by the artist; it is impressive in its volume but impossible to read. This work has been interpreted in diametrically opposite ways by two different critics, Gao Minglu and Norman Bryson, in the catalog for the exhibition Inside Out: New Art from China, held at the Asia Society and PS1 in 1998, in which it was included.1 According to Gao, the work represents an emptying of meaning, in keeping with Buddhist notions of negative space, opening a door to viewers’ interpretations. To Bryson, the work is a reaction to political and economic forces occurring in China that are breaking down unification in society to the point where shared understanding is impossible. Both interpretations are valid but reflect very different notions of “Chinese-ness,” with Gao Minglu finding the work to be essentially Chinese because there is a continuity between this contemporary creation and a traditional Chinese outlook, while Bryson regards it as a form of political expression particularized by conditions in China.

XU BING, BOOK FROM THE SKY, 1987–91, INSTALLATION VIEW, NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA, 1998. COURTESY OF XU BING STUDIO.

Similarly, Zhang Xiaogang has one idea about how he came to make his famous Bloodline series, but curators and critics have interpreted the work quite another way. In this series, nuclear families—mother, father, and child—are presented in frontal poses, facing the audience with blank, emotionless expressions. In some, the family appears in Mao jackets, the omnipresent garb of the Cultural Revolution; in others, a thin red line and sheer patches of color connect the figures. These monochromatic compositions, as austere as black-and-white photographs from another era, are similar to Rorschach tests, inviting viewers to come up with their own interpretations not only of the artworks but of recent events in China.

When he started the series in the early 1990s, Zhang Xiaogang had no idea that these solemn characters would become the face of Chinese contemporary art. In 1995, Zhang Xiaogang presented his Bloodline: Big Family series in an exhibition entitled The Other Face: Three Chinese Artists as part of the larger international exhibition Identità e Alterità, installed in the Italian Pavilion during the 46th Venice Biennale. Since then, they have appeared in hundreds of exhibitions and on the cover of auction catalogs, an instantly recognizable iconography that is easily dispersed and understood globally. “This is as strange to me as it is to you,” Zhang says to me. “Frankly, I was just concerned with what work I should make to continue being an artist.”

Indeed, the Bloodline series was the result of a crisis of faith when Zhang Xiaogang saw that he had to reject Western influences in his work such as Surrealism and expressionism to come up with something original. Stymied in his development, in 1992 he fled to Europe, where he stayed for three months, visiting 20 or 30 art exhibitions. In the end, he returned to China, determined to find something authentically Chinese to express in his work. He found it while flipping through old photographs in his parents’ house dating back to the 1960s and 1970s, capturing the family at the time of the Cultural Revolution.

“In the 90s, it was important to discover one’s own identity. As it was the transition period from Chinese communism to a capitalist market economy, the immediate crisis for me was a crisis of identity,” says Zhang. “I was very lost at the time. This difference in identity prompted people to choose between two paths: either join in with international standards, or go back to traditional culture to find one’s roots. I chose to delve into contemporary history to discover my own cultural legacy.”

Upon further reflection, he uncovered three strains to Chinese identity that he considered essential, namely “western modernism, socialism and traditional Chinese culture.” After his sojourn as a foreigner in Europe, he came to realize that “it was very important for a Chinese artist to be conscious of his or her identity, because China was way too different from the rest of the world.” This realization allowed him to delve into a more intimate approach to art-making, one that transcended abstract theories and burdensome art history. “My biggest gain from the trip was the realization that art is life—it was an overwhelming feeling,” he says.

So, Zhang Xiaogang’s emphasis on a Chinese identity is not the result of isolation and ignorance of Western art practices, but a reaction to his initial embrace of those trends. In Europe, he faced his crisis head-on by seeing the masterpieces of Western art history and feeling as if there was nothing more he could add to that legacy. Back in China, however, he was surrounded by a new cultural experience that could not be captured through Western iconography and symbols. His rejection of the West was not total. Instead, he embraced an approach that allowed for innovation in both Western and Chinese traditions for art. This can be seen as a series of abandonments: firstly, a rejection of the Socialist Realism that he studied at the academy; secondly, abandoning his reliance on Surrealism and expressionism; and finally, synthesizing aspects of Surrealism and Western oil painting with imagery derived from recent Chinese history in order to develop his own unique vocabulary.

Because the figures in his paintings are clearly Chinese, even when they are not in Mao suits, it is almost too easy to use them as an example of “Chinese-ness.” Far more fascinating is the fact that Zhang Xiaogang felt that he had to struggle to find a Chinese identity in order to continue making art and came to the belief that his work should reflect the Chinese experience. Though not unique to China, and certainly evident in the works of artists from many cultures around the globe, this search for identity underscores how confusing life in post-Mao China was in the 1980s and 1990s, where the fanaticism and idealism of the Cultural Revolution was supplanted by the greed and competition of a capitalist economic system. Many of the artists emerging in the 1990s shared Zhang Xiaogang’s dilemma and devoted their time to exploring the meaning of Chinese identity.

“I remember that I gave a lecture in the US around that time and I talked about the fact that China is so young, only 30 years old, but it was a very lonely country and it is this loneliness that I sought to convey through my family portraits,” he explains. But often, these paintings were given a pointedly political meaning, either as a critique of the Cultural Revolution or of the emotional harm caused by the One Child Policy. To this artist, these meanings were not his initial intention, though he does not object to people finding evidence of recent Chinese history and political conflicts in his work. “Maybe the day when our historical reality overlaps with that of Europe, there would no longer be any Chinese elements in our artworks,” he says. “Chinese elements cannot be seen as simplistic visual codes, but rather something more profound. Sadly, many artists today supe...