eBook - ePub

Breaking the Cycle of Mass Atrocities

Criminological and Socio-Legal Approaches in International Criminal Law

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Breaking the Cycle of Mass Atrocities

Criminological and Socio-Legal Approaches in International Criminal Law

About this book

Breaking the Cycle of Mass Atrocities investigates the role of international criminal law at different stages of mass atrocities, shifting away from its narrow understanding solely as an instrument of punishment of those most responsible. The book is premised on the idea that there are distinct phases of collective violence, and international criminal law contributes in one way or another to each phase. The authors therefore explore various possibilities for international criminal law to be of assistance in breaking the vicious cycle at its different junctures.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Breaking the Cycle of Mass Atrocities by Marina Aksenova, Elies van Sliedregt, Stephan Parmentier, Marina Aksenova,Elies van Sliedregt,Stephan Parmentier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & International Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Cycle of Mass Atrocities

1

Introduction: Breaking the Cycle of Mass Atrocities: Criminological and Socio-Legal Approaches to International Criminal Law

I.The Cycle of Mass Atrocities

International criminal law addresses dramatic situations in the collapse of societal structures leading to the inability of various actors to distinguish between ‘good’ and ‘evil’. ‘Collapse’ does not necessarily entail physical destruction or dissolution of institutions responsible for the enforcement of values, although this is a very common scenario, but may also occur in the presence of authoritarian non-accountable institutions acting as a ‘façade of justice’, while in reality serving as an instrument of oppression.

Christian Gerlach’s concept of ‘extremely violent societies’ is helpful in explaining the general loss of a moral compass in society.1 Gerlach does not define violence as a structural or cultural characteristic and permanent condition of societies but rather locates events and maps campaigns triggering further escalation.2 Such description accurately captures the state of confusion accompanying war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, jointly known as ‘atrocity crimes’ or ‘mass atrocities’.3 These crimes are manifestations of collective violence perpetrated during periods of chaos. They are particularly heinous because they threaten the survival of entire communities. These are not singular instances of criminal conduct but rather symptoms of a bigger crisis in the respective society. Rwandan genocide, for example, was preceded by decades of successive victimisation of Tutsi and Hutu communities – a situation leading to perpetual re-enactment of onslaught and culminating in one of the most brutal massacres of the twentieth century.4

The terminology of ‘atrocity crimes’ used in the title of this book follows the concept introduced by David Sheffer in 2002 to reflect the law of international criminal tribunals and subsequently adopted by criminologists and official UN bodies.5 In the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document, United Nations Member States made a commitment to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, a principle referred to as the ‘Responsibility to Protect’.6 The purpose of inventing the legal concept of ‘atrocity crimes’ was therefore to highlight the importance of timely intervention of the international community during the early phases of such crimes.7 The emphasis is thus on the escalating nature of collective violence with less severe crimes, such as forcible transfer or looting, often preceding more serious crimes, such as genocide.8 This approach stresses the fluid nature of collective criminality, making the terminology of ‘atrocity crimes’ most suitable for distinguishing between different stages of collective violence.9

The present volume investigates the role of international criminal law at different points in time in the course of collective violence. It shifts away from law’s narrow construction solely as an instrument of punishment of those most responsible for mass atrocities10 and rather views it as a broader force, which is both practical and universal.11 International criminal law enables the dissemination of norms about the prohibited conduct and sets the standard for behaviour in conflict situations. A good example to illustrate the wider implications of international criminal law, which go far beyond mere adjudication, would be the effect of the ratification of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) on deterrence. Studies show that ratification of the Statute and not necessarily the engagement of the ICC as such created certain deterrent effects in a number of African states.12

In this vein, one can view international criminal law as a point of refence for, or a measure of, international consensus about universally condemned conduct. Cultural criminology provides a suitable theoretical framework for this statement. Criminologist Wayne Morrison observes that life is anchored in fixed points of symbolic reference, or monuments, that incorporate and preserve a sense of collective identity (for example, the Statue of Liberty). On a non-physical plane, he continues, the legal order serves as a vitally important monument.13 Globally, formal recognition of human rights is one of the pillars of the emerging universalist legal order and a symbol of consensus.14 Mass atrocities are human rights violations on a big scale and they shake the consciousness of humanity as a whole by undermining this order. Their occurrence is thus a reminder of the need for accountability, but it is also a call for action to prevent future escalation. With such a strong symbolic appeal, international criminal law bears prospective qualities and must be viewed in broader temporal terms.15

The foundation of the discussion in the present volume is the contextual embedding of mass atrocity crimes. The work of Susanne Karstedt is helpful in understanding this context. Karstedt views atrocity crimes as linked to macro conflicts and micro dynamics at the local level. This vision follows from her understanding of mass atrocities as a phenomenon to be studied both in the light of the general structures of international power relations and technologies of war and by identifying localised events, patterns of victimisation, involvement, and resistance at the community level.16 This book however suggests a somewhat different approach. Instead of focusing on ‘general-to-specific’ dimension of mass atrocities, it rather examines its individual stages and possible causal linkages between them. Individual stages form a cycle, which serves as a starting point, or a framework, assisting in studying collective violence and the role international criminal plays in containing it. The cycle points to the fact that mass atrocities and tensions preceding them are not singular events but rather that they keep occurring over a prolonged period of time, manifesting as a symptom of a society exposed to violence and oppression.17

The cyclical nature of collective violence is reinforced by recurrent events unfolding during shorter temporal intervals and often serving as a build up for a major genocidal event.18 For example, in Guatemala, the period of extreme violence starting in 1977 was preceded by more than a decade of lower intensity crimes such as arbitrary executions and torture.19 A more recent example is the persecution of the Rohingya Muslims and other ethnic minorities in Myanmar. The UN Fact Finding mission found that the process of ‘othering’ the Rohingya had started long before the worst atrocities unfolded.20 It follows that mass atrocities are not exceptional, or ‘one-off’, incidents but rather repetitive occurrences.21 Having said that, it is fair to assume that the cycle of mass atrocities, in its various manifestations, has features that distinguish it from ‘regular’ criminality usually tackled by domestic criminal law.

Admittedly, representing criminality as a cycle risks painting the picture in black and white, obfuscating important nuances and using a general mould to fit a variety of scenarios. The point here is rather to use the cycle as an analytical tool for understanding the wider context of collective criminality and without a claim to its universal applicability.

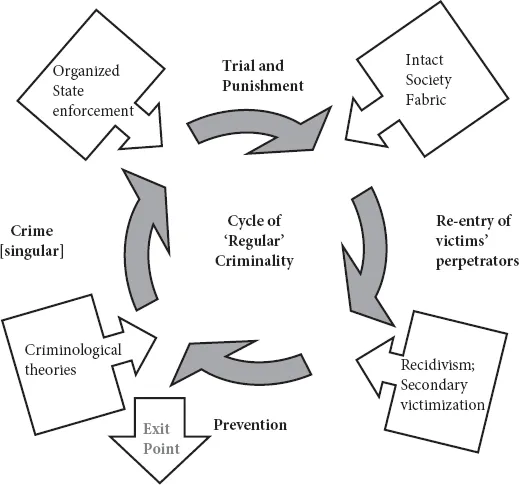

This volume contrasts the cycle of mass atrocities with the cycle of ‘regular’ criminality and argues that these are different processes. What is it then that makes the cycle of collective violence unique? Schemes 1 and 2 presented below demonstrate crucial distinctions. Scheme 1 outlines the phases of ‘regular’ criminality in a society not affected by conflict, while Scheme 2 visualises the cycle of mass atrocities divided into various stages. A brief comparison of these two diagrams demonstrates varying levels of contextual embedment of the two cycles of criminality, with collective violence posing additional challenges both in the area of prevention and enforcement. The ‘regular cycle’ comprises the following steps: offence, criminal justice’s response to it, reintegration of former perpetrators into society, and prevention. The cycle of mass atrocities derives its distinctive features from the context in which it occurs and incorporates the following stages: the commission of a crime; criminalisation of the relevant conduct; punishment of those responsible; re-entry of victims and perpetrators into society; and prevention.

The key distinctions lie in the nature of the conduct in question: as a rule, the cycle of ‘regular’ criminality includes singular instances of offending, whereas mass atrocities are by definition a collective endeavour. The reaction to these crimes varies as well and depends on whether there exists effective enforcement. Societies experiencing extreme violence are unlikely to have the resources and political support for effective and fair investigations. Moreover, the cycle of regular criminality presupposes that the offences are criminalised well in advance, while ‘criminalisation’ becomes a separate step in the cycle of mass atrocities because the content and variety of offences under international criminal law are continuously expanding. The stage of ‘re-entry of victims and perpetrators’ within the two processes intends to achieve different goals: while international criminal law and other transitional justice mechanisms aim to rebuild trust in society and mend its torn fabric, domestic instruments grapple with the issue of recidivism, which may or may not be as pronounced in the context of collective violence. The challenge for international criminal law therefore is to respond to the specific type of criminality.

Scheme 1 Cycle of ‘Regular’ Criminality

Finally, the emphasis of most domestic criminological theories is on preventing deviant behaviour because the aim is to reduce incentives for offending. Crime and social control are therefore objects of study within the field of criminology. The purpose is to answer the primary question about how and why people come to act in violation of the law.22 As a result, criminological theories do not only explain crime but also contribute to its prevention, thereby providing an ‘exit point’ from the cycle of offending. Paradoxically, while national policymakers have long benefited from criminological science when crafting responses to various types of offence, advocates of international criminal justice still rely on sporadic surveys and work in the absence of reliable empirically tested theories.23 Possible explanations for this vacuum in the field of international criminal law lie in the difficulty of developing plausible theories accounting for mass criminality.

The patterns of collective offending are not so easily broken down into single analytical pieces. Such patterns often emerge from complex organisational hierarchies and shifts in the psychology of persons exposed to the severe stress of war and violence. Would traditional criminological theories explain the processes leading to mass atrocities? Let us take, for instance, ‘neutralization theory’, which is prominent in many domestic criminological explanations of criminal behaviour. This theory, developed by Sykes and Matza, argues that much delinquency is based on what is essentially an unrecognised extension of defences to crimes.24 The delinquent justifies his or her deviance by reasons appearing as valid to him or her but not to the legal system or society at large.25 Neutralization theory thus focuses on life narratives and the offender’s self-representation. In line with this subjective approach to understanding criminality, modern ‘cultural criminology’ aims at integrating creative and interpretative practices into the study of crime. Wayne Morrison insists that much criminality is a way of reclaiming self-control in situations where the locus of this control is lost outside the self, due to immutable societal structures.26

Both the neutralization theory and the postulates of the cultural criminology lead to the conclusion that changing faulty cognitions in individual offenders may be less of a psychological or clinical matter than a sociological one.27 In a follow-up analysis to the Sykes and Matza study, Copes and Maruna identify research confirming the idea that all of us make predominantly external attributions for our failures and predominantly internal attributions for our successes.28 If failures are attributed to external societal factors, then deterrence efforts are also to be focused on changing an offender’s way of relating to them rather than just working with his internal psychological state of being. Copes and Maruna further ‘normalised’ human justificatory processes, stressing that neutralisation techniques are commonplace and do not necessarily attest to the existence of a ‘criminal personality’.29 The same possibly holds true for high-level perpetrators. Stanley Cohen notes that politicians, military commanders and industrial leaders might be said to owe their careers to their ability to neutralise.30

It is plausible to apply neutralization theory and its extensions to the context of mass atrocities.31 However, there are some peculiarities and limitations. What is particularly striking is that the atmosphere of lawlessness accompanying the rupture of society creates a uniquely fertile ground for attributing one’s conduct to externalities (orders by superiors, despair, confusion about the value of human life). One could call this phenomenon ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- List of Cases

- Part I: Cycle of Mass Atrocities

- Part II: Criminalisation

- Part III: Trial and Punishment

- Part IV: Re-Entry of Victims and Perpetrators

- Part V: Prevention

- Epilogue

- Index

- Copyright Page