1

Mrs Petrov’s Shoe

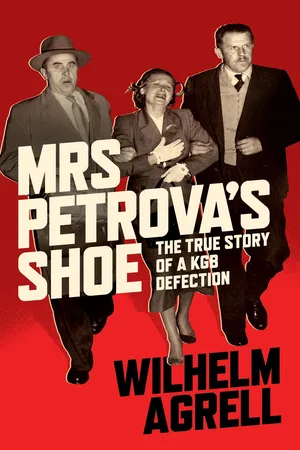

The two men are holding the woman between them in a firm grip. In one hand she is carrying her handbag; the other hand she places on her heart. The man on her right stares into the camera lens with his lips parted. His colleague stares resolutely ahead, beyond the photographer, towards something outside the picture. But there is also something else, something missing. The despairing woman being dragged away is wearing only one shoe. The scene appears to have been composed as painstakingly as one of the Old Masters’ martyr portraits, with each detail designed to reinforce the overall significance. But whose martyrdom is being depicted in this way? From which Cold War film has the scene been taken? The Third Man, perhaps, or, more likely, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, with the totalitarian security service’s brutal henchmen carting off their defenceless victim to be tortured and executed.

However, the woman in the picture is not a well-known actress. She has certainly performed different roles and has been educated and trained for this. But here, in front of the flashlights at Mascot Airport outside Sydney, she seems to be just playing herself. Her name is Evdokia Alexeyevna Petrova, and the scene immortalized by an attentive press photographer is the prelude to one of the early Cold War’s great spy dramas.

Evdokia Petrova, the woman who has just lost her shoe in the turmoil, was, from the beginning, a minor character in a complicated intelligence operation. The main role was played by her husband, Vladimir, whom the Australian Security Intelligence Organization (ASIO), kindly assisted by its far more experienced British MI5 colleagues, had for several years been ‘grooming’ as a suitable candidate for defection. To the extent that Evdokia even featured in the equation, she did so as an operational problem and a potentially disturbing factor. Once her husband had finally been persuaded to take the decisive step and had climbed into one of ASIO’s cars, ASIO made every effort to get as much information out of him as quickly as possible before the Soviet authorities understood what had happened and began to take familiar steps. The prognosis for defectors was not a particularly good one, especially if they came from the military intelligence service or, like Petrov, from the omnipotent security service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD), the predecessor to the Committee for State Security (KGB).1

Neither ASIO nor MI5 knew from the outset who Vladimir Petrov was. But while they continued to groom him, they received indications from various sources that he was no ordinary Soviet diplomat with a predilection for Sydney’s nightlife; instead, he had other duties. One of these tip-offs came from the Swedish Security Police, which held information about Petrov, who between 1943 and 1947 had been stationed at the Soviet legation in Stockholm. Once ASIO had reeled in its prey, it could finally see what a big fish it had landed; Petrov was in actual fact the resident, the head of the embassy’s secret intelligence station.

The few Soviet intelligence officers who had previously defected had done so along with their loved ones, very conscious of the fate that would have otherwise awaited them. But when Vladimir Petrov got into the car that was waiting for him, he did not take his wife with him but a collection of classified documents from the residency’s safe, documents that served as a defector’s combined dowry and insurance policy. This moment was also immortalized, not by a press photographer but by a picture taken by one of the ASIO officers present, showing a hunched man in a suit ducking into a waiting car.

Evdokia Petrova was still in the dark. Perhaps her husband had taken his life; maybe he had been kidnapped by the enemy. She received no word from the embassy, just an order to fetch the most essential items from her home and assurances that she would be under guard. Petrova was then confined to the building while awaiting Moscow’s decision, which came in the form of two armed KGB men arriving to ‘escort’ her to her homeland, and if this failed, they were under orders to ensure that she did not fall into enemy hands alive. One defector was already one too many.

Who was she, this woman who with the flash of a camera was transformed into a Cold War icon and a symbol of the fight between good and evil? When she was led out to the waiting plane, ASIO and MI5 had already been clearly informed by her husband that this was no ordinary childless diplomat’s wife who handled the embassy’s administrative work. She was in fact a trusted colleague and one of the very few women to be promoted to the rank of officer within the Soviet security apparatus. The Australian authorities put forward a futile proposal to the Soviet embassy to arrange a meeting between Vladimir and his wife, but the Australian agent who had wormed himself into the couple’s favour had firmly advised against any such contact. In his opinion, Evdokia intellectually dwarfed her husband, and any meeting might therefore have an undesirable and perhaps devastating outcome. Moreover, one defector was more than enough for the Australian authorities, whose relations with the Soviet Union were already at breaking point.2

MI5, the newly formed ASIO’s perpetual and discreetly present mentor, was, however, interested in hauling in the entire booty, in what was given the cover name Operation Cabin 12. The BOAC plane was scheduled to make a stopover in Darwin first before continuing to the then Crown Colony of Singapore, where they would make their move. The primary target was not Petrova but the fourth person in the party, the MGB cipher clerk Philip Kislitsyn, who had also been recalled to Moscow. Early in the questioning, Petrov had told how Kislitsyn had confided in him that while posted in London he had handled reports from centrally placed Soviet agents.

The Australian authorities had trumpeted Vladimir Petrov’s defection as a major foreign policy coup, and the event was well timed for the government, which was facing new elections. The politicians took a more cautious approach to dealing with Evdokia, though; they were certainly happy to grant her asylum if she so requested, but they were not prepared to actively intervene in the course of events. If she went with her executioners, they could do very little other than wash their hands of the situation. But the commotion at Mascot Airport, where the Soviet party ended up in the middle of a heated crowd, threatened to overshadow all this and make the government and the authorities appear powerless against this brutal assault. Prime Minister Menzies received a first-hand report from the airport and realized that they now needed to change course to avert a domestic policy catastrophe and a subsequent election defeat.3

During the Darwin stopover, available police and security agents had been mobilized. They overpowered and disarmed the two KGB men, Yarkov and Karpinsky, on the grounds of breaching air safety. Vigilant press photographers were also on hand to capture the heavily built Karpinsky being wrestled to the ground. After the commotion, the responsible government official there first arranged a telephone call between the spouses and then a short private conversation with Evdokia where she finally, and with great hesitation, uttered the words protocol demanded: she wanted to remain in the country. A drama in two acts had thus been played out in less than twelve hours, or as historian Robert Manne summarized the prevailing mood: ‘At Mascot the forces of Good and Evil had contended; at Darwin Good had triumphed.’4

While both the international and Australian press described what Vladimir Petrov had initiated and his wife had completed as a romantic escape to freedom, the reality behind the headlines was entirely different. Vladimir had fled because of his recall by Moscow, where he expected to pay the price for professional incompetence and his previous loyalty to the liquidated minister of the interior, Lavrentiy Beria. Evdokia was gradually faced with the choice between accepting the same fate as her husband or allowing the retributions to be exacted on her family, her parents and her little sister, Tamara. Evdokia had not defected to freedom but had been forced to step into a vacuum.

Australia was a peripheral arena in a Cold War that was mostly other people’s business and fought along front lines in other parts of the world. But the Petrovs’ defection suddenly brought the Cold War to this distant and politically peaceful continent. What had previously shaken Western Europe, and more so the United States, had now broken out in Australia: the hunt for the Soviet intelligence service’s agents and sympathizers, and with that the link between the external and internal enemy in the form of the Australian Communist Party and its open or secret sympathizers.

The Australian government quickly set up a Royal Commission to investigate Soviet espionage in the country. What the Australian public and the rest of the world came to know as the Petrov Affair had now begun: a protracted legal and political battle that would culminate in the Labor Party splitting into right and left factions, ensuring that Prime Minister Menzies would remain in power for the next 12 years. As a result of its domestic policy repercussions, the Petrov Affair would cast its shadow over the Australian public for a very long time, with lingering suspicions that several individuals had served as tools for Soviet intelligence or had operated in the legal and ethical grey area between normal social or professional contacts and spying. But just as long-lasting were the suspicions that Prime Minister Menzies and his confidant, Director General of ASIO Brigadier Spry, had actually staged the defection to discredit the leader of the opposition, Herbert Vere Evatt, by revealing that some of his staff were part of the circle which had been in contact with Soviet intelligence. Many people regarded Menzies’s triumph in Darwin, followed by his parliamentary election victory, as evidence of political manipulation of the worst conceivable kind.

All this was a mystery to the Petrovs, and no concern of theirs anyway; they were simply pawns in a big game they had no idea they were playing or any control over. In reality, they were kept under house arrest in a ‘safe house’, constantly watched and monitored. No unpremeditated events were allowed to disrupt the plan either inside or outside the safe house. In parallel with the Commission’s largely public process, another, more prolonged and probing process was secretly taking place, namely the central element of the Australian–British intelligence operation, internally known as ‘the Exploitation of the Petrovs’. During the endless questioning, everything of intelligence value was to be extracted, not just information mainly concerning Australia. The Petrovs’ information provided clues to several of the great Cold War spying affairs, including the then partially uncovered Cambridge Spy Ring, and there were suspicions that other senior Soviet agents had infiltrated the British secret services. But the clues also led to Sweden, where the couple had been stationed between 1943 and 1947. Through British MI6, the Swedish Security Police (Säpo) were brought into the investigation; this cooperation was extremely politically sensitive but also regarded by the Swedes as important enough to outweigh the risks. The couple knew practically everything about the entire Soviet intelligence network during their years in Sweden but were also aware of individuals involved in various phases of the recruitment process or, using Soviet terminology, ‘objects of study’.

Time after time, the interrogators went through the long lists of questions, sometimes including new information or a picture from a collaborating security service. One of the things the interrogators discovered concerned not these factual matters but the people who were being interrogated. The entire operation had started with the assumption that it was the KGB resident, Colonel Vladimir Petrov, who was the big fish in the net. But the longer the questioning went on, the clearer it became that Evdokia was not just any old by-catch they could just as well have thrown back into the sea; she was actually the most credible and, in some important aspects, most knowledgeable informant of the two. When questioned, she seemed the total opposite of the apparently helpless woman who had been dragged away at Mascot Airport. She was general material, with intellectual capacity and willpower far exceeding her rank of captain. So, if she actually was – and remained – much more of a professional intelligence officer than her husband and was not really a defector at all, then why did she choose to cooperate? This is one of the questions at the very heart of the Petrov Affair, one which the interrogators failed to ask and which remained unanswered.

As the years went by, the wheels of the interrogation machine trundled slower and slower before finally coming to a halt. At the end of the 1950s, MI5’s liaison officer had no choice but to report to London that the Petrovs were now definitely ‘out of production’. Their exploitation had come to an end, and terminal storage had commenced. The couple were and remained irretrievably shackled to each other, under constant surveillance. Officially, this was for their own safety, but had they been prone to making imprudent statements, this could have caused trouble or even been dangerous for the organizations that had taken over control of their lives. One thing was absolutely clear from the outset: they would never be allowed to return; their change of sides was irreversible.

In 1996, Robert Manne was granted an interview with Evdokia, who by then was in her eighties.5 Vladimir had died a few years earlier after a long illness. The Petrov Affair certainly had a life of its own, but Evdokia had become less and less plagued by journalists ferreting around to find her address so they could interview her. The KGB death squads, which Vladimir had lived in constant fear of, had never worried her. The great scar she bore was not fear but her longing for the Russia she had lost, and no Australia in the world could replace this. She told Manne of a recurring dream she used to have where she was strolling along Lubyanka (a street in Moscow) and came upon the street where her family lived, the communal apartment she had moved into as a child in the 1920s and where her family had continued to live for a long time. In her dream, she always reached the building but could never enter.

Manne asked her about the dramatic circumstances surrounding her captivity at the embassy, the men dispatched from Moscow and the scenes at Mascot Airport. He enquired whether she had been afraid, but she dismissed this suggestion. What about the tears then? Yes, they were genuine enough, but had been cau...