- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

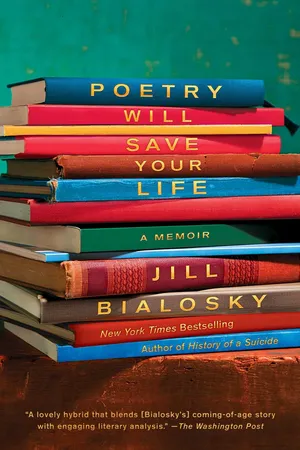

From a critically acclaimed New York Times bestselling author and poet comes “a delightfully hybrid book: part anthology, part critical study, part autobiography” (Chicago Tribune) that is organized around fifty-one remarkable poems by poets such as Robert Frost, Emily Dickinson, Wallace Stevens, and Sylvia Plath.

For Jill Bialosky, certain poems stand out like signposts at pivotal moments in a life: the death of a father, adolescence, first love, leaving home, the suicide of a sister, marriage, the birth of a child, the day in New York City the Twin Towers fell. As Bialosky narrates these moments, she illuminates the ways in which particular poems offered insight, compassion, and connection, and shows how poetry can be a blueprint for living. In Poetry Will Save Your Life, Bialosky recalls when she encountered each formative poem, and how its importance and meaning evolved over time, allowing new insights and perceptions to emerge.

While Bialosky’s personal stories animate each poem, they touch on many universal experiences, from the awkwardness of girlhood, to crises of faith and identity, from braving a new life in a foreign city to enduring the loss of a loved one, from becoming a parent to growing creatively as a poet and artist. Each moment and poem illustrate “not only how to read poetry, but also how to love poetry” (Christian Science Monitor).

“An emotional, sometimes-wrenching account of how lines of poetry can be lifelines” (Kirkus Reviews), Poetry Will Save Your Life is an engaging and entirely original examination of a life while celebrating the enduring value of poetry, not as a purely cerebral activity, but as a means of conveying personal experience and as a source of comfort and intimacy. In doing so the book brilliantly illustrates the ways in which poetry can be an integral part of life itself and can, in fact, save your life.

For Jill Bialosky, certain poems stand out like signposts at pivotal moments in a life: the death of a father, adolescence, first love, leaving home, the suicide of a sister, marriage, the birth of a child, the day in New York City the Twin Towers fell. As Bialosky narrates these moments, she illuminates the ways in which particular poems offered insight, compassion, and connection, and shows how poetry can be a blueprint for living. In Poetry Will Save Your Life, Bialosky recalls when she encountered each formative poem, and how its importance and meaning evolved over time, allowing new insights and perceptions to emerge.

While Bialosky’s personal stories animate each poem, they touch on many universal experiences, from the awkwardness of girlhood, to crises of faith and identity, from braving a new life in a foreign city to enduring the loss of a loved one, from becoming a parent to growing creatively as a poet and artist. Each moment and poem illustrate “not only how to read poetry, but also how to love poetry” (Christian Science Monitor).

“An emotional, sometimes-wrenching account of how lines of poetry can be lifelines” (Kirkus Reviews), Poetry Will Save Your Life is an engaging and entirely original examination of a life while celebrating the enduring value of poetry, not as a purely cerebral activity, but as a means of conveying personal experience and as a source of comfort and intimacy. In doing so the book brilliantly illustrates the ways in which poetry can be an integral part of life itself and can, in fact, save your life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Poetry Will Save Your Life by Jill Bialosky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Collections. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

MOTHERHOOD

THE POMEGRANATE

ON MY FIRST SON

FUNERAL BLUES

NICK AND THE CANDLESTICK

My first child is a daughter. I remember exactly the day we conceived. It was in the early hours of New Year’s Day after returning home from a long, snow-filled walk from lower Manhattan (impossible to get a cab on New Year’s Eve) where we celebrated the New Year eating bowls of pasta and sharing a bottle of Chianti at a local Italian restaurant. I know I am pregnant almost instantly. I’ve wanted to be a mother for as long as I can remember, hoping to create for my child the stable childhood that was stolen from me when my own father died. For months before she is born, I imagine her. We have our own secret language. When we are alone, lying on the couch or taking a walk in the park I feel her move to the rhythm of my breath. She hiccups when I do. I feel her blood churning in mine, changing the chemistry of my breathing, my digestion, the way I talk and feel. My stomach looks like I’m hiding a bowling ball underneath my sweater. It’s hard and full and when I walk I sometimes cup my hand underneath my panty-line to make sure she doesn’t drop. I walk through the park and watch the young children playing in the playground or skating at the ice rink. Do all mothers imagine their daughters to be mini-versions of themselves? I hope she won’t have the traits I dislike about myself. I want her to be bright and confident. I am already giving her advice in my own head. I play music for her. I have a library of books all picked out. I walk past baby stores and stare at the mannequins, the little girls dressed in polka dot dresses and Mary Janes. When I give birth prematurely at thirty-two weeks, I know before I see her exactly what she will look like, and I’m right. She has my round face and wide forehead. There are complications and I’m rushed to the operating room for an emergency C-section. Her lungs collapse ten minutes after she is born. Against all we are prepared for, our baby does not survive. The idyllic image I have held of her and our lives together, our family, is shattered. For weeks I can’t take it in. It is surely a combination of pregnancy hormones still ruling my body, producing milk in my breasts, making my uterus contract, and my desire to not quite let her go. I refuse to talk to anyone, rapt as I am in my private universe with my daughter, unable to fully accept that she is gone.

THE POMEGRANATE

Eavan Boland (1944–)

The only legend I have ever loved is

the story of a daughter lost in hell.

And found and rescued there.

Love and blackmail are the gist of it.

Ceres and Persephone the names.

And the best thing about the legend is

I can enter it anywhere. And have.

As a child in exile in

a city of fogs and strange consonants,

I read it first and at first I was

an exiled child in the crackling dusk of

the underworld, the stars blighted. Later

I walked out in a summer twilight

searching for my daughter at bed-time.

When she came running I was ready

to make any bargain to keep her.

I carried her back past whitebeams

and wasps and honey-scented buddleias.

But I was Ceres then and I knew

winter was in store for every leaf

on every tree on that road.

Was inescapable for each one we passed.

And for me.

It is winter

and the stars are hidden.

I climb the stairs and stand where I can see

my child asleep beside her teen magazines,

her can of Coke, her plate of uncut fruit.

The pomegranate! How did I forget it?

She could have come home and been safe

and ended the story and all

our heart-broken searching but she reached

out a hand and plucked a pomegranate.

She put out her hand and pulled down

the French sound for apple and

the noise of stone and the proof

that even in the place of death,

at the heart of legend, in the midst

of rocks full of unshed tears

ready to be diamonds by the time

the story was told, a child can be

hungry. I could warn her. There is still a chance.

The rain is cold. The road is flint-coloured.

The suburb has cars and cable television.

The veiled stars are above ground.

It is another world. But what else

can a mother give her daughter but such

beautiful rifts in time?

If I defer the grief I will diminish the gift.

The legend will be hers as well as mine.

She will enter it. As I have.

She will wake up. She will hold

the papery flushed skin in her hand.

And to her lips. I will say nothing.

This poem, by the Irish poet Eavan Boland, articulates the umbilical bond between a mother and a daughter. It is an open-ended poem. Any mother can enter it, whether her child is alive or dead. It takes as its understory the myth of Persephone and Demeter, the mother who lost her daughter to the underworld and bargains her back for half the year. Even after a child dies, a mother continues to live her life through imagination. As each year passes, she thinks of her, of what age she’d be, imagining her among the girls she sees dressed in their school uniforms walking to school, or a girl walking hand in hand with a boy, wondering what she would look like, who she would become. “If I defer the grief, I diminish the gift,” Boland expresses, juxtaposing the mythic underworld with the world of the everyday—of Diet Coke and teen magazines and cable television. About this poem and motherhood, Boland writes: “Motherhood was central for me—I mean as a poet, as well as in every other way. ‘The Pomegranate’ came out of a series of realizations like that. And having said that, I don’t think I realized at the beginning how much the perspective of motherhood could affect the poem in strictly aesthetic ways. Take for example the nature poem: when I was young and studying poetry at University I had a very orthodox, nineteenth century view of the nature poem. That the sensibility of the poet was instructed in some moral way by the natural world. And it was an idea I just couldn’t use. I couldn’t get close to it. But when my daughters were born, that all changed. I no longer felt I was observing nature in some Romantic-poet way. I felt I was right at the center of it: a participant in the whole world of change and renewal. “The Pomegranate” is a sort of nature poem in that way—there’s a deeply seasonal aspect to the raising of children. And I wanted to write that.”

After a year passes, we decide to try to have another baby. When I become pregnant again it’s different. I’m apprehensive. I can’t quite take it all in. We take precautions. I’m on bed rest and am given a procedure to prevent premature labor. I am carrying a boy. Alone during the day, friends bring me muffins and coffee and stay for a bit to chat, but I can’t really pay attention. I’m already trapped in the otherworld, communing with my little boy. Judy, who comes to clean my house, helps me now with groceries and meals. As she is dusting the bedroom, she tells me that more than one clock in a room means death. There is an alarm clock propped on the nightstand like a little soldier of attention and on my bookshelf, a small Tiffany silver clock, a wedding gift commemorating the passing of time with elegant Roman numerals. I am propped on one side to keep the nutrients flowing for the baby and ask Judy to take the Tiffany clock and put it in the living room. Once she leaves and the apartment is quiet again, an ominous shadow descends, and the room darkens, though it’s not quite four. I am obsessed with my pregnancy. I look in the mirror when I get up to go to the bathroom and worry that I am carrying small. When I was pregnant with my daughter, I was almost twice the size. The next morning, Judy tells me that boys carry differently than girls, but I don’t believe her. I call the doctor because now I think I don’t remember the last time I felt the baby move. I press my hand on the lower part of my abdomen to see if he will respond, but there is no movement. It all happens quickly. I’m in a cab, then the doctor’s office getting a stress test, and within the hour in the cool antiseptic operating room of the hospital being prepped for a C-section. It turns out that all the hours of lying on one side was futile. The baby isn’t getting enough nutrients and has to come out of the compressed womb of my birthwater into the light of day to grow in an incubator. It is too soon. My boy is born at twenty-six weeks. He’s so tiny you could hold him in one hand, and yet his features are unmistakably those of my husband’s. Within twenty-four hours, his kidneys fail him. “My sin was too much hope of thee,” writes Ben Jonson, a contemporary of Shakespeare, in this moving exploration of the loss o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Preface

- Discovery

- Danger

- Wonder

- Selfhood

- Memory

- Shame

- Ancestors

- War

- Prayer

- Imagination

- Death

- Poetry

- Family

- Fathers

- Faith

- Foreboding

- Depression

- Envy

- Sexuality

- Escape

- First Love

- Mothers

- Friendship

- Passion

- Legacy

- Marriage

- Grief

- Suicide

- Motherhood

- Terror

- Mortality

- Mystery

- Notes on Contributors

- Permissions

- Acknowledgments

- Reading Group Guide

- About the Author

- Notes

- Copyright