![]()

INTO THE UNKNOWN

The year was 1964, and I was twenty-one, soon to be twenty-two. The sign on the bulletin board read “Student North American Club,” offering a chartered flight to New York and back—three months in the summer vacation—for £55. Amazing! Maybe I can go? A friend said: “Yes, it’s a good deal. I went last year. You should go, why not?” Thinking fast; could I make it? I could visit New Orleans and try to get a job there to pay for the trip. I will have completed my physics degree course at Newcastle University, so why not? Then it all seemed to happen so suddenly, so quickly. The opportunity appeared, a door opening to a new world lying ahead. I knew that somehow I could do it but, as usual, my outward expression was calm and did not betray my inner excitement. I was used to going into the unknown and was never afraid to take a chance. My frequent hitchhiking up and down the A1 from Newcastle-Upon-Tyne in the North East of England to London and back had never been a problem, turning out to be a reliable form of travel. So what could possibly go wrong with a trip to States? I was in part naive, part devil-may-care, and part adventurous.

Making the arrangements began immediately. I asked a friend of the family who lived in San Francisco to sponsor me so I could get a “Green Card,” the permanent resident visa, which would enable me to work. The interview at the US Embassy in London went smoothly—there were no restrictions or waiting lists in those days—and approval came a couple of months later. I had always taken jobs during university holidays to pay for my extra expenses, and now I was saving up for my trip. What a change this would be!

Although I grew up in London, my parents had recently moved to Church Stretton in Shropshire and, after many years in London, really enjoyed living in a small town in the country. Knowing I needed to save money for my trip, they helped by hiring me to clear some of their hugely overgrown and long-abandoned garden. The Long Mynd hills were right behind their house, and Wales was just a few more miles to the west. There was a golf course up and down the steep slopes of these hills that must have been the most strenuous in the world, and was great for tobogganing when it snowed in the winter. A steam traction engine rally was held in the fields around the town each year, and that was the first time I heard a steam-driven calliope. The sound echoed up and down the valley.

I don’t remember how I got to London from Church Stretton, as we were not on any main road. But perhaps I had a ride to Shrewsbury—we were a mere thirteen miles to the south—and hitched to London from there. The wealthier class pronounced it SHROWsbury, but I never identified with them, so pronounced it SHREWsbury like the majority. Many of my new friends in the traditional jazz world of London, since we had only recently met, thought I came from Shropshire.

“You’re getting away again,” my sister Clare told me. My other sister Elizabeth had recently “got away” by taking a job as a secretary for the Royal Horticultural Society in Cambridge. That was arranged by my dad as she had been getting increasingly depressed living at home in London. My brother Mark was able to go to Cambridge too, following in his father’s footsteps with a singing scholarship to Clare College, later studying divinity and becoming an ordained priest in the Church of England. My younger sister Clare was stuck at home longer, as she depended on our parents to help her through university. She took biology at London. I began finding ways to “get away” from home in my teenage years. There was something liberating and, as you will read later, even necessary about getting away from home. Even my long bicycle trips exploring London were a big relief. Once, when I was eleven, I had an accident and suffered a concussion. It was my fault, but since then I have followed the rules of the road meticulously. My escape to the States, both from family and country, beckoned—an adventure, a path to follow. I simply jumped at the chance, just following my nose, as it were, knowing nothing of what lay ahead, but excited about the unknown, completely unaware of anything in my future that would result from my actions.

The chartered flight was the longest journey I had undertaken—about ten hours in those days including a refueling stop in Gander, Newfoundland. Having paid my transportation in advance—a Greyhound bus ticket cost ninety-nine dollars for ninety-nine days—I arrived in New York with only fifty dollars in my pocket. I was counting on getting a job to pay for the summer. By chance I recognized another student from university on the flight over who knew of some cheap addresses to stay in Manhattan. We ended up in a sort of hostel for homeless, runaway kids that was, in a way, kind of appropriate. Costing one dollar a night, it was on the Lower East Side. Knowing nothing about New York, that was quite accidental. But there I was in the old Russian and Ukrainian Jewish quarter, now also inhabited by the bohemian crowd who had recently moved over to escape the rising rents of Greenwich Village; it was a decidedly hip part of town.

My first impression of the States was of New York City—the noise, everything moving fast, the yellow cabs, hundreds of them, the almost continuous ambulance and police sirens, the energy. It was hot, dry, and dusty, yet the nights were comfortable. People were friendly. The very next day some of the bohemian types I met took me to the bar where the Beatles had spent a night and recommended many other things to do and see—like eating borscht in a Russian restaurant—that were unusual for me, coming as I did from a conservative British background. At night I heard the great trumpet player Henry “Red” Allen at the Metropole, and the New Orleans drummer Arthur “Zutty” Singleton at Jimmy Ryan’s. As I could afford only one drink in each place, I would stand outside the Metropole, which was close to Times Square, and listen to several sets. The musicians would come out on the sidewalk to smoke a cigarette in their breaks. I plucked up enough courage to say hello to Mr. Allen, who seemed to tower above me, and told him I was on my way to his hometown New Orleans. His eyes lit up for a moment: “Have a good time,” was all he said as he walked back to the bandstand.

After a few days I was riding the bus to San Francisco to visit my sponsor. You met all kinds on the bus so it, too, was an adventure. In fact, my first extended visit to the States was an adventure in trust. Everyone traveled by bus in those days except for the few who could afford to fly. I could get off and on wherever I liked, so took a route that passed by Flagstaff, Arizona, in order to visit the Grand Canyon. In those days Flagstaff was nothing but a little way station for visitors. It was a dry, semi-desert area surrounded by mountains covered in scrub. I tried to make the most of my one-day visit by walking halfway down into the canyon on a trail. That was a mistake as climbing back out was incredibly exhausting and took hours. Luckily there were water stations at regular intervals, but that was hardly sufficient. Hot, dusty, and dry, I climbed back into the bus to connect with the Greyhound bus which took me into San Francisco overnight. My arrival coincided with the Republican Convention, featuring the nomination of their candidate for president, a race between Goldwater and Rockefeller. As I got off the bus I found myself at the end of a demonstration against Goldwater and his public pronouncements on bombing Vietnam with nukes, if necessary. Goldwater won the nomination, but ultimately lost the presidential race to the Democrat candidate and incumbent president Lyndon B. Johnson, who had been Kennedy’s vice-president.

My sponsor Norman Smith, an English friend of my family, had once been a curate training under my father in our Church of England parish. Having lived in Japan for many years, he loved the Japanese culture of San Francisco, and took me to a neighborhood restaurant where we were the only non-Japanese. He ordered everything in fluent Japanese. Ironically, he was off to Britain in a few days, so undertook to acquaint me with all his favorite haunts immediately. This included visiting the Episcopal cathedral, which I found to be decidedly opulent, largely due to the extravagant tastes of Bishop Pike—an eccentric, go-get-’em type. The bishop achieved some notoriety later when he wrote a book about looking beyond the grave for evidence of his son, who had committed suicide. After retiring, Bishop Pike began searching around Israel where his son had died, and eventually disappeared without a trace in the desert. When Norman drove me north to the California redwoods, everything seemed so different, so new, so vast, so exciting. The final year of my degree course had been grueling, and a complete change was just what I needed. But impatient to move on, I found myself once again on a three-day bus ride to the city of my dreams, New Orleans. At that time it never occurred to me to stay longer than the summer.

![]()

GROWING UP IN LONDON

For a long time, New Orleans had grown in my imagination. New Orleans jazz represented so much that I may never be able to put into words, but has fascinated me ever since I first heard that Bunk Johnson recording. A trumpet player who began playing at the turn of the twentieth century, Bunk was famous for his tone and inventive, rhythmic style. He recorded for the first time in the 1940s. Until then, I had never heard any jazz and almost no popular music of any kind.

The son of an Anglican clergyman, I grew up in St. John’s Wood, a quiet residential area of northwest London, close to Regent’s Park, Lord’s Cricket Ground, and only two Underground stops to Baker Street. I walked to school and back, crossing Abbey Road by the EMI Studios where the Beatles later recorded. We lived in the vicarage next to the church on Hamilton Terrace, which was the widest residential street in London with a row of plane trees on either side. The grounds around the church and our garden were extensive, and part of my chores was to cut the grass each week in the spring and summer. It took two hours.

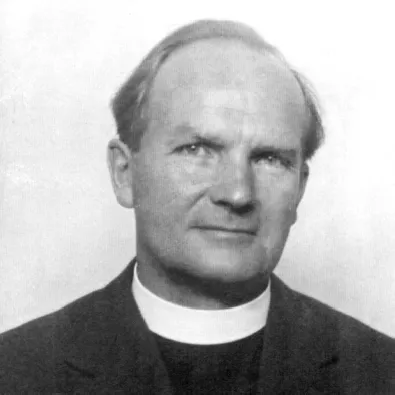

My father loved classical music and could have been a professional tenor. As he couldn’t stand popular music and musicals, even his admiration for Paul Robeson was tempered by his dislike of his recording of “Ol’ Man River.” Be that as it may, I must have inherited my musical sense from my dad. He loved the sound of the trumpet, and I remember him playing me 78s of the Haydn trumpet concerto when I was quite small. My dad sang ecclesiastical tenor with the choir, and often with a professional quartet that sang anthems for our Sunday morning service. He also sang solo tenor in productions of the Messiah and the Saint Matthew Passion. He had so much volume when he sang in the congregation that the rest of us in the family were a little embarrassed. I am the oldest of four children with two sisters, Elizabeth and Clare, and a brother Mark, who died in 2013. All of us took piano lessons for a while and Mark also played flute and organ.

Bill Wilson, my dad, as I remember him, ca. 1959. Donated by Margaret Wilson to the Clive Wilson collection.

As I write this, a vague and rather odd memory comes back to me:

I am playing a toy drum in a Christmas end-of-term show for parents. I am five. Everyone in the class is playing a drum to accompany our teacher at the piano. It sounds pretty chaotic as no one else in the class can keep time including one boy who is trying to conduct. I am so frustrated by this that I bang louder on my drum to try to get everyone together. So the teacher calls me up from the back row to take a turn conducting and I love it! But she doesn’t like me, never did, and sends me to the back row again after one short piece.

My dad is quite excited to see me up there in front of everyone, the only one in kindergarten who can keep time. But he is pretty annoyed with the teacher. My mother is proud of me, but has a worried look on her face, that frown she often has. I imagine she thinks: No way! No drum set in our home! All that noise!

So that was the beginning and end of my drumming career.

As my first teacher disliked me, she made me feel pretty miserable at times. Maybe that had something to do with the ear infection I came down with that kept me out of school for many months. Although nothing seemed to work, it did eventually get better. I was kept back in the second year, because I had difficulty learning to read and do simple arithmetic. Eventually, the teacher in the third-year class (third grade) took a special interest in me and got me over the hump of learning the basics. However, I was eleven (in seventh grade) before I finally caught up with my own age group.

As for music, we had a school choir, but that was all. I was a member for a while because I could sing in tune. It was my dad’s passion, so he was eager for me to pursue singing. At another school concert for parents when I was seven or eight years old, we sang the Ave Maria. I remember him feeling that was a mistake as he thought it too difficult for us at that age. He was a perfectionist. But later he told me we don’t sing that in the Church of England because we don’t worship the Virgin Mary like the Roman Catholics. That seemed a pity as I enjoyed the melody.

My dad had been a chorister as a boy. When his voice broke he stopped using it altogether for two years, even talked in whispers to protect it until it settled. He continued his training and won a singing scholarship to Clare College at Cambridge. After he decided to become a minister, singing took second place, but he remained a perfectionist whenever he performed music or church services. Unfortunately he and I had a problem. I wanted his approval, but he was not around that much. Nowadays I see him as a workaholic. I think he was avoiding closeness and felt uncomfortable with emotions. A product of his times at the beginning of the twentieth century, he believed in an old-fashioned way of bringing up kids, which I’m sure he had experienced himself. He didn’t approve of too much holding and touching for boys. My mother later told me that when she was a young mother, she was quite influenced by this advice from both my father and her in-laws, and was often torn between that and following her own instincts. So, at least overtly, I didn’t feel close to my dad. I felt a distance between him and myself, and I learned very early to do without his help. This was unusual, as most of my school friends liked to do things with their fathers.

We did some things together, of course. My dad played cricket and spent quite a bit of time giving me batting and bowling practice in the nets at Lord’s Cricket Ground, which was just up the road from where we lived. He was a member of the Middlesex Cricket Club (MCC). But, unlike my brother, I didn’t have the eye-to-ball coordination to become much good. Later, beginning when I was about eleven, he dug out all his old conjuring tricks and taught me to use them. My dad used to be a conjurer when he was in university. Although I loved working with the illusions, the sleight-of-hand tricks required considerably more practice and skill that I never mastered. Nevertheless, I put on a couple of successful shows at my primary school. I remember feeling both nervous and excited to perform in front of the other kids.

In my generation, families ate all their meals together, and conversations at the table could get quite lively. Once when I was eight and had just realized that Santa Claus was really my parents, I asked my dad how he could possibly believe in God when He was invisible. I was challenging him. “I don’t see Him, so I don’t believe He exists,” I said. I must have hit a raw nerve: although it was very rare for my dad to show his anger—he avoided it if at all possible—he became infuriated with me for questioning the central fact of his life, his commitment to serving God, as he put it. His reaction was so unexpected that I went numb with shock and never dared to bring up that topic again. Today I wonder about that moment—his eldest son asking a philosophical question! He could have talked about Santa Claus, for example. Even though we cannot see him, the spirit of giving is nevertheless alive when we give gifts to each other at Christmas. Does God exist when we help others? I feel he missed a wonderful moment.

Like most children, I asked a lot of questions growing up but I could never get a straight answer from my dad. He fenced around the subjects, pretending to know so much, but never actually answering my question. Since he was brilliant at waffling around the topic and not coming to any definite opinion, I found him maddening and began to withdraw from him, keeping to myself. Sometimes I’d be so angry I’d stomp out and slam the door behind me.

Perhaps for that reason I did not relate to church. I never knew what to do there but sit it out. Growing up in a vicarage meant going to church on Sunday morning and Sunday school in the afternoon. On top of that, we read selected passages from the Bible at the breakfast table every day. I certainly became familiar with scripture. But enough was enough, so I said no when my dad asked me if I wanted to sing in the choir. That would have meant more choir practice and singing at more services, and I had quite enough church and religion to deal with as it was. A few years later I quit singing in the choir at school, probably because I associated it with church.

My mother was close to us because she was around all day long, except when we went to school. Her family meant everything to her and she had a hard time giving us up when we became old enough to move on. She would do too much sometimes. Helping me with my homework, she even wrote all my compositions for the English class until I was found out. I took an exam at eleven years old and could only write two lines. So they knew my mother had been doing it. But as soon as she stopped helping me, all of a sudden I could write about anything. It seemed I had picked up the ability from watching her.

At the same time that she had this desire to help us, she was the one who got angry. But she was unpredictable, which all of us found hard to deal with. Sometimes when we were naughty, she’d laugh it off. The next time she might explode with rage and banish us to our rooms until she had time to cool off. She also reacted if she thought there was any possibility of inappropriate sexual...