![]()

Part One

THE WORK OF

JAZZ

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Jazz

Let us start with the “jazz” element of a “work of jazz” before considering this expression as a whole.

Many attempts at defining jazz have been made, and it has proved a difficult enterprise. Results are unclear, yet this has not stopped the music itself from flourishing. What is clear is that no definition has been reached that everyone can more or less agree on. The evolution of jazz since the 1960s and 1970s has made the task even more complex. Some people argue that jazz itself does not exist anymore but, as a fact, a tradition has continued, specific practices are observable, and jazz “worlds” exist. A form of continuity, though not linear, is there to be seen and allows us to talk about jazz even if the boundaries of the music are hard to pin down.

1. A FRAMEWORK FOR A DEFINITION

The choice seems to be between three main tendencies, each of them reflecting one of the three main approaches to the object. The first option is historical and focuses on the history of jazz and its evolution. The second option is sociological and anthropological. It looks for a definition exploring what is sometimes called the “context,” that is to say the environment in which a type of music emerges at a certain time: when it emerges, among which communities, their position in society, the social, historical, racial, and cultural circumstances of that time, etc. The third option is properly musicological and investigates the nature of the object and what makes it evolve by looking mainly at musical features.

The definition appears equally difficult to reach whatever option is chosen—and perhaps it is a sterile debate to have. We may be better off not deciding which option seems best. All three approaches are justified and do not need to confront each other. In fact, they are not mutually exclusive at all and tend to actually complement each other in practice. However, it is perfectly fair to be interested in one more than the other, even if they all deserve further investigation.

2. THE HISTORICAL ASPECT OF THE MATTER

Should we give up our attempt to reach a definition because it has proved difficult so far? No, though many authors have used it as an excuse to find it a vain and useless search. Rather, we should use these difficulties as a reminder to remain cautious and moderate.

Let us start with the musical point of view. When attempting to define jazz there are three criteria analysts most often examine: a sound different from anything heard before, a certain approach to rhythm (swing), and improvisation. Problems appear immediately: there is no specific “jazz sound,” so to speak; there are types of jazz devoid of swing as it is traditionally understood; and there are works of jazz that are almost totally composed (the vast majority of them being partially composed). Perhaps combining the three criteria might be a solution, as it is difficult to conceive that a piece could be totally composed, devoid of swing, and without any of the sonic traces usually associated with jazz, and still be jazz. But this only transfers the problem to a different level, for none of the three notions—sound, swing, and improvisation—can be defined easily if they have to be considered together.

The matter is actually eminently historical. Jazz has evolved very quickly. What can be identified of the early days of jazz dissolves as the language of jazz expands and as the music becomes more diverse. In the early days, the use of the drums was new and thus perceived as characteristic. Later on, it became banal and at the same time the uses became more diverse. Drums even disappeared from some jazz bands. In the same way, the “sound” of jazz rapidly grew more diverse as well as less specific. The same thing can be said about swing. Things are less clear about the historical aspects of improvisation, however. Anyway, a feature that seems characteristic at one point in time is not always so at another.

The historical dimension of the problem suggests that it can be addressed with a historical division of time that would be based on the main phases of evolution of the musical language rather than on the history of styles (knowing that the two approaches may or may not coincide). The idea behind this division is that a language of jazz exists, and that it has gone through a phase of stability, preceded by a phase of formation, and followed by another during which that language loses its dominating position. I propose to accept the concept of a “common practice” of jazz, understood as a model similar to its equivalent in the classical tradition, which corresponds more or less to the period of domination of the tonal system (approximately 1600–1900), as an object of reference. Specific problems in analysis arise outside of that phase, whether we deal with pre-tonal or post-tonal music. An analogous phenomenon happens about jazz: it is possible to define a “common practice” within which a number of features have developed to form a musical language that has been stable for a while and has operated in a spirit of consensus. What would the features of that language be?

- Harmony:

• A mix of tonal harmony and blues

• A system of harmonicity (ways of laying out chords and linking them together)

- Form:

• Form of composition: there is a limited choice (mainly AABA, ABAC, and blues)

• Form of performance: supremacy of the head-solos-head form

- Rhythm:

• Stable and isochronic beat

• Common time (4/4) and other duple meters (2/4 and 2/2)

- Codes of play:1 mostly walking bass and ching-a-ding

- “Acoustic” instrumentation:

• Melodic section: trumpet, saxophone, clarinet, trombone, violin

• Rhythm section: double bass, drums, keyboard, banjo, guitar, vibes

These combined features may define a common practice in jazz,2 in which they all or mostly occur together except on very rare occasions. Historically, it becomes possible to identify this common practice around 1930, when all the features mentioned above existed individually and functioned together in a typical manner. Everyone seems to accept this manner or common language and its supremacy does not get questioned. For about thirty years, all jazz was based upon it. Even if the dissidence had been stirring throughout the 1950s, with noticeable gradual changes taking place, it is only in 1960 that free jazz and jazz known as “modal” appeared and started challenging some of the features described above (or all of them). The early 1960s mark the end of the supremacy of a certain system and language of jazz. It stops dominating the production of jazz but does not disappear. The features listed above continue to exist.3 What happens would be more aptly described as a broadening of the language.

Such a historical division of time puts the seismic shift toward bebop in 1944–45 in perspective. Whether bebop was an evolution or a revolution is one of the most frequently recurring issues in the musicology of jazz. When André Hodeir suggested in 19544 that bebop marked the transition from a classical era to a modern era in jazz, there was every reason to believe that it was indeed a radical evolution (though perhaps not a revolution, as there were many signs of continuity). This point of view has possibly changed. If Hodeir had been told at the time, “bebop marks a break, certainly, but still uses the walking bass, ching-a-ding, and the head-solos-head form,” he would probably have replied that those features were components of jazz itself and that without them the music we were talking about would not be jazz. And what would he have said about the isochronic beat at the heart of the system, the very condition of swing that was nevertheless challenged by free jazz? It is always easier to notice what has changed rather than what could have changed but stayed the same. The questions of identity versus otherness, repetition versus difference, and the historical dimension of phenomena are raised in their full complexity.

This explains why Hodeir and others have identified 1945 as the turning point between a classical and a modern age in jazz. Nowadays it seems fairer to place the cursor on the year 1959, when Kind of Blue by Miles Davis and Giant Steps by John Coltrane were recorded, followed in 1960 by Free Jazz by Ornette Coleman. From this viewpoint, the 1930–60 period makes up a new classical age based on the common practice.

What are the features of jazz before 1930, then? It seems logical and appropriate to our scheme to define a pre-classical age. It would end when the classical age starts, in 1930, but when would it start? People agree to consider the recording of “Livery Stable Blues” and “Dixieland Jass Band One-Step” by the Original Dixieland Jass Band on February 26, 1917, as the first jazz recording. The date is a benchmark for the beginning of a history of jazz in the sense that this is when phonographic traces started being available, with the consequence that the music became directly accessible through recordings. However, jazz existed long before then, even if it is only possible to know about it through visual (photographs, drawings) or verbal testimonies. It is now considered that the early days of Buddy Bolden’s orchestra in 19005 mark the true birth of jazz. Following in the footsteps of historian Daniel Hardie, this period may be called “elemental jazz.”6 It would be squeezed between a sort of prehistory of jazz (that could start with the Emancipation Proclamation) and its history proper starting in 1917. There is a contradiction here: on the one hand, it is stated that history would start with phonographic documents (1917), but on the other hand we recognize that jazz exists as early as Buddy Bolden (1900). This can be solved by choosing 1900 as the beginning of the history of jazz strictly speaking, while keeping in mind that history for the period of elemental jazz is only based on oral, written, and iconographic documents; the difference in sources of the history change drastically once mechanical recordings appear.

What about post-classical periods? If 1960 is the accepted date marking the beginning of a modern age, does the period have an end or are we still in it? A phenomenon needs to be taken into account: the last identified style of jazz—jazz-rock (or fusion)—is complete around 1975. More than the end of a style that has followed others, this marks the end of a long cycle and breaks up a chain in which historians identified a style following another at a steady pace, usually periods of between five and ten years: New Orleans style to start with, followed by pre-swing (or Chicago style), swing, bebop, cool, hard bop, free jazz and simultaneously modal jazz, and jazz-rock. It is not possible to continue a so-called “main linear scheme.”7 Indeed, periods have been identified based on processes that showed a degree of repetition and were characterized by a dominating style and the masters of that style. Such a type of identification is not possible after jazz-rock. Since the second half of the 1970s and up until today, it seems we have been witnessing a process of multiplication (there are more and more musicians) and atomization at the same time: it has become more difficult to group musicians based on a shared style. Rather, there are tendencies, movements, and affinities. Most importantly, none emerges as dominant and as a potential indicator of a period of time.

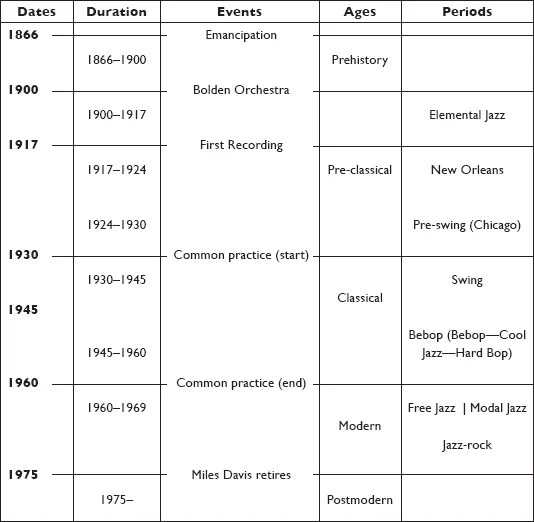

TABLE 1. AGES AND PERIODS IN HISTORY OF JAZZ

While jazz has become incredibly diversified, this is not new; from its beginnings jazz has been the result of mixing ingredients, but the contemporary level of proliferation is unprecedented in its history. At the same time, we observe a new awareness of history and the emergence of neo-classical styles. It is tempting to see evidence of postmodernism in all this, which is not surprising considering that that discussion has been raised about numerous other artistic practices.

There is no need to look into this matter any further for now and I propose to end the modern era in 1975, when a postmodern age would start in which are still living now.

This leads to table 1, which differentiates between ages and periods (some ages encompassing multiple periods).

3. SUGGESTIONS FOR A DEFINITION

The debate about a definition of jazz changes depending on the time period we are talking about: before, during, or after the classical age (which is the least challenging to define).

What did the first investigations of jazz come to, and which criteria were suggested for defining it? First of all, it is worth noting that the need for a definition has always been strongly felt, which is perhaps not the case for all types of music. Jazz has always questioned its own identity and has constantly required redefinition. It is interesting to note that a definition has often proved problematic for jazz musicians themselves; even the most famous of them have sometimes decided not to try. Duke Ellington preferred to think that he was making music rather than jazz (“I am not playing jazz. I am trying to play the natural feelings of a people”).8 Miles Davis saw racial connotations to the word “jazz” that he felt were irrelevant to his music. Nowadays many musicians prefer to define themselves as improvisers rather than jazz musicians.

It is also worth remembering that jazz technically is a type of music, not a genre and certainly not a style. It does explore a number of genres and of course it has produced styles. In the early days (for Jelly Roll Morton, for example), jazz was sometimes seen as a certain way of making music, but that has not been the case since then.

Before jazz itself was on the scene, two elements—identified as striking as a new type of music—seemed to be coming up. The first was the close link that these new types of music had with African Americans and their culture; today this would be called “ethnicity.” The second feature was the presence of syncopation. Sound soon came to be considered a third criterion of definition. Jazz was perceived to seek out “strange sounds.” A debate started in the 1920s about whether or not improvisation was essential, but it soon began to be considered another crucial feature. The final feature to join the list of criteria for a definition of jazz was swing, understood as a particular treatment of rhythm and a development of syncopation.

Identifying a range of characteristic features does not automatically lead to a definition, however. As a result, it could be tempting to conclude that it is pointless (suspect, even) to try and mark the boundaries of jazz with a definition that would restrict it esthetically and, as a possible consequence, could deny it the capacity to evolve. Nevertheless, the accusation of essentialism that is often brought into the debate, to try and put a stop to efforts to reach a definition, seems even more authoritarian. Also, ignoring the issue does not make it disappear.

The way out of this labyrinth requires going back to the criteria already mentioned: syncopation, African American music, sound, improvisation, and swing. As said before, these are the criteria that emerged from the way music known as jazz was received throughout the twentieth century. Can they help produce a definition of jazz that works and is suited to the purpose of this book?

It is worth noting that four of these criteria are specifically musical while one (community-based) is socio-anthropological. It appears that none of them is either necessary nor sufficient in reality. It is possible to come across jazz without syncopation, jazz played by non–African Americans, jazz devoid of a specific sound, jazz without any improvisation or any swing rhythm in the strict sense of the word. On the contrary, if none of these ingredients is present, it will be hard to perceive the music heard as jazz. Conversely, if all five markers appear together, it is very likely that the sample being scrutinized can be...