![]()

The heavens declare the glory of God, and the firmament sheweth his handywork. |

| |

Geographical inscription is simultaneously material and imaginative, shaping landscapes out of the physical earth according to human intentions: both the demands of practical existence and visions of the good life. Geographical representations – in the form of maps, texts and pictorial images of various kinds – and the look of landscapes themselves are not merely traces or sources, of greater or lesser value for disinterested investigation by geographical science. They are active, constitutive elements in shaping social and spatial practices and the environments we occupy. Reading landscapes on the ground or through images and texts as testimony of human agency is an honourable contribution for cultural geography to make towards the humanities’ goals of knowing the world and understanding ourselves: to the examined life.

The first verse of Psalm 19 introduces a tradition of linking vision – the cosmic glory of God – with order, his handiwork within geographical space.

Insofar as human geography concerns the natural or physical world, geographical space remains space that can be seen, or at least visualized. The different resonances of vision and visualizing constitute my theme. At its simplest, geographical vision ranges over space, but geographical space exists in historical time, involving contingent relations between an active observer and the field of observation. Vision is more than optics and perception, as I have already pointed out, and cultural geographers have carefully dissected many of its ideological complexities and tensions.1 Vision also implies reworking – and pre-working – experience in the world through imagination, and imagination’s expression in the creation of images. Geography (geo-graphia) has always entailed making and interpreting images.

The scales of geographic vision

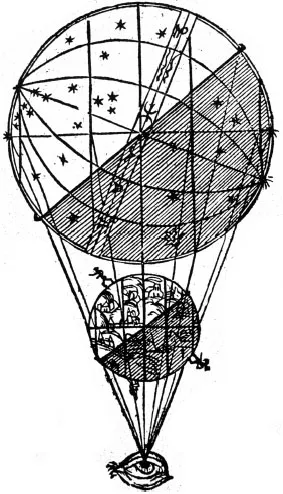

Psalm 19’s hymn to the spaces of creation echoes historically, from St Augustine to John Ruskin, as a theological justification for scientific enquiry into external nature, and indeed for geographical exploration itself. As the science of ‘discovery’, geography provided an early template and a term for the central objective of the Baconian scientific project of bringing speculation and observation into a coherent discourse. The psalmist proclaims the world as a unitary creation, the work of a transcendent agent bringing form and order out of an original chaos of material elements. Simon Girault’s 1592 book Globe du monde illustrates the psalm through the image of the spherical machine of the world turned through its diurnal revolution by an unseen hand. For cosmographers such as Girault, observation of God’s creation reveals to human creatures the traces and the presence of divine handiwork. Through observation humans may learn to penetrate the always labile and contingent surface appearances of the world, and disclose its more enduring form and order. In the world’s form and order, vision invokes evidence of design, a sacredness on earth.

This belief, that the world itself provides visual evidence of consistent order and design, whether sacred or secular, remains remarkably robust historically, in the face of insistent human experience of chance, contingency and unpredictability – deified as Fate or Fortune – as fundamental to the ways of the world.2 Its articulation in the West owes as much to Greek as to Judaic thought. In his cosmological text, the Timaeus, Plato described an orderly creation whose hidden form may be rendered visible by mathematics, specifically geometry. Pythagoreans had advanced similar arguments, suggesting that geometrical ‘harmony’ was sensibly apparent to human eyes and ears (the German word Stimmung captures this sense better than any English term). Literally, geo-metry means ‘earth measurement’, a practice that the Ancient Greeks believed had originated in Egypt, where the annual Nile flood erased all visible property boundaries, necessitating astronomical observation – the sun’s shadow cast across the earth by a gnomon (a stake or obelisk) – in order to fix and re-inscribe them upon the undifferentiated space left by the retreating waters. The historical truth of this account is of less importance than the fact that it binds the localized and domesticated human landscape of cultivated fields and farms to the divine firmament of rotating planetary bodies. Geometry maps celestial order onto terrestrial space and makes visible divine handiwork through an act of human imagination and intellection.

Conceiving the universe as a divine geometrical exercise focuses attention on its structure: on a skeletal system of points, lines and motions.3 An alternative rendering, most obviously traceable to Aristotle’s Physics, drew attention to the fabric of creation and to the earth as a body within it, of mass and volume, composed of tangible and corruptible elements, which required a temporal process of separation from an originally undifferentiated chaos. Light had to be separated from darkness, water from earth, for any semblance of balance and harmony to be established and sustained within the corruptible elemental sphere. This cosmogony too could be observed along the Nile, as a cultural landscape of bounded and differentiated spaces was annually recovered from the confused chaos of earth and water left by flood, and the earth once more made productive. These accounts of order in the body of the world both concern geographical form: geometry describes its spatial structure, and physics its elemental nature. Until Newton’s time, the science that synthesized these accounts into a reasoned description of the material universe was cosmography.

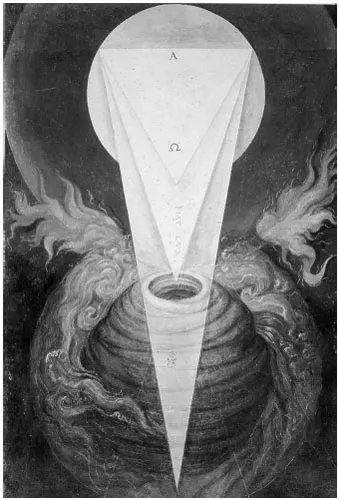

Girault’s Globe du monde is a work of cosmography. Like the Renaissance natural philosophers whose work he synthesized, Girault drew fairly promiscuously upon Christian doctrine, classical authority and empirical observation to generate his vision of the world.4 The most important source and authority for cosmographers at Girault’s time of writing remained Claudius Ptolemy, the first century CE author of two great scientific summaries of ancient locational knowledge: the Almagest, which described the pattern and movement of the heavenly bodies, and the Geography, which described the pattern of climates, lands and seas on the terrestrial globe. From these works Renaissance cosmographers such as Regiomontanus (Johann Müller), Martin Waldseemüller, Oronce Fine, Peter Apian or Sebastian Münster developed an ordered classification representing the earthly globe and its place in the universe at diminishing scales.5 They established a threefold spatial hierarchy made up of cosmography, geography and chorography (Fig. 1.1) Cosmography dealt with the whole system of the geocentric universe, treated either mathematically as a system of forms and motions, or descriptively in its vastly varied and differentiated contents. Geography described the large-scale pattern of climates, lands and seas on the surface of the globe, and could be logically connected to cosmography mathematically and thematically through measured scale. Chorography limned local regions, or landscapes. Each of these sciences was a ‘-graphy’ (-graphia), not a ‘-logy’ (-logia). In other words, each of these discourses was constructed primarily through images rather than words; each appealed to the logic and authority of the eye and the inscription of form as much as to scriptural authority or formal syllogism.6 A graphic imperative informed the work of the cosmographer, whose primary appeal was to vision: to make visible, at each of these descending scales, the order and harmony, and the contents of creation. Theologically speaking, if the text of God’s glory was the Bible, elucidated by hermeneutics and written commentary, the image of God’s handiwork was the visible world, whose order was exposed in mathematical diagrams, globes, maps and paintings. If the scholastic might offer a commentary of the text of Genesis, the cosmographer’s task was to reveal its cosmogonic narrative to the human eye, as is demonstrated by the opening images of Hartmann Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493, building from the simplest geometrical figure of the circle to the great picture of God the Father enthroned at the centre of the ordered cosmos; or the mid-sixteenth-century Portuguese artist Francisco de Holanda’s spectacular images of elemental parturition on the First Day, or the creation of sun and moon on the Fourth, all subject to the all-seeing eye of a Creator who is at once geometrical and corporeal (Fig. 1.2).7

Figure 1.1 Peter Apian, Cosmographic relations of the spheres viewed from nowhere, Cosmographicus Liber, Landshut, 1524, fol. 1v (UCLA Library Special Collections)

Figure 1.2 Francisco de Holanda, Fiat Lux: image of the first day of creation, De Aetatibus Mundi Imagines, 1543–73 (Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid)

I shall deal more fully with cosmography in Chapter 2. My concern here is those more terrestrial scales of geography and chorography to which geographical science is now perhaps too completely confined.8 So exclusively has the contemporary secular vision become limited to ‘spaceship earth’, that many students of geography scarcely appreciate the significance of planetary arrangements for patterns of climate on the earth’s surface. Yet until very recently, geographical learning began with the aid of an orrery or celestial diagram, intended to explain those purely conceptual lines of equator, tropics and polar circles described by the motion of the axially angled earth around the sun, whose geometry binds terrestrial and celestial spheres.9

Cosmographic vision

Cosmography intersects with geography in the great circles of equator, tropics and poles that encircle the globe and from which originate the ancient Greek idea of torrid, temperate and frigid zones, with all their ethnographic baggage. The desire to envision a consistent global order, beyond the scale of direct local experience, suggested not only a formal symmetry of global climate, but also of lands and seas (Fig. 1.3). Balancing continental landmasses in each hemisphere were believed to be surrounded by Ocean – a geographical descriptor that in Greek denoted a primeval slime of undifferentiated elements (apeiron) rather than open sea, a space wholly alien to the ordered landscapes of civilized urban life at the temperate centre of a habitable oikoumene.10 The sixteenth-century French explorer Jacques Cartier and his settlers would pay the price of a Quebec winter for their inherited belief in parallel climatic zones, wherein a St Lawrence Valley January should resemble mild winter along the River Loire, because both occupy the same latitude. Similarly, until the eighteenth century, a great southern continent endured on world globes and maps, mute testimony to the lasting desire for symmetry between continental landmasses in the two hemispheres, while the original edition of Mercator’s famous world map shows four rivers flowing from an open polar sea into a viscous ocean.

Figure 1.3 Aurelius Theodosius Macrobius, Mappa mundi showing the climatic zones and balancing hemispheric continents separated by the Ocean Stream, In Somnium Scipionis exposition, Lyon, 1550 (UCLA Library Special Collections)

As geographical discovery revealed a pattern of lands and seas, environments and peoples quite different from that predicted by the theoretical geometries of astronomical geography, Europeans responded in two ways. Some quite ruthlessly imposed their visions of spatial order across conquered territories through the applied geometry of geodesy, survey and cartography, while others imagined ever more esoteric symmetries hidden beyond the earth’s surface geography. I offer examples of each of these in turn.

Navigating seas, oceans and unmapped continental interiors depended upon astronomical observation and mathematical calculation, but they are practical activities than do not depend upon a geodesic framework. Throwing an imaginary lattice of longitude and latitude across the globe is, however, a prerequisite for projecting the spherical earth onto a flat map and accurately coordinating information about lands and seas into a single image. The grid’s projective geometry made the earth visible and itself became a powerful stimulus to further visions of spatial order.11 The grid’s hubristic implications are suggested by the anthropomorphic wind heads, located at the cardinal points of many early world maps. Their interlocking gaze across the global surface signifies a divine, all-seeing, omnipresent eye, while their breath represents the spirit moving over waters and lands, animating the earth.12 The eschatological significance of these figures is indicated by their regular conflation with angels, sounding the apocalyptic trumpet from the four corners of the earth. Yet the wind heads’ gaze from the frame of the map is also a cartographic expression of the human conceit of special status in the order of creation: hovering between angelic and animal nature, able, in imagination at least, to escape the bonds of earth and encompass with the mind’s eye its magnitude and plenitude. The grid itself resonates with the preternatural power these angelic wind heads signify.

The most consistent, extensive and permanent visible landscape trace of Europe’s colonization of global landscapes during the half millennium between the mid-fifteenth and mid-twentieth centuries is the territorial inscription of cartography. The graticule, geodesy and the grid were practical tools of empire and modernity. Within a year of Columbus’s first Atlantic voyage, Pope Alexander VI, claiming global authority from Christ’s universal redemption, drew a meridian through a still virtual oceanic space to separate Spanish from Portuguese world empires, at that point no more than flags and padraõs dotted along the map’s uncertain coastlines. The line of Tordesillas, extended 35 years later by the Treaty of Zaragoza to encompass both hemispheres, was a geometrical fiat that still defines the linguistic geography of the South American continent.13 The territorial divisions and agrarian landscapes of the United States and Canada, Australia and many parts of South America and Africa are a lattice of straight lines and right angles, testifying to the imposition of the cosmog...