- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

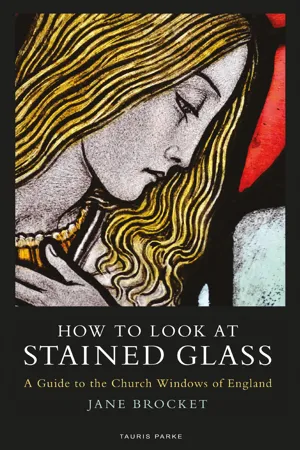

About this book

A fresh, unstuffy guide to the stained-glass windows of England's churches, including a list of the top 50 places to see outstanding examples.

The magical qualities of stained glass have an enduring appeal, but church windows tend to be ignored as a form of creative and artistic expression. Yet churches are accessible treasure trove of history, art and craftsmanship. No other set of historic buildings with such superb and important architectural and artists assets is as easy to visit. How to Look at Stained Glass is the companion guide that's needed to make sense of and enjoy the vast array of stained-glass windows in the churches of England.

This fresh, unstuffy guide:

- Uses an A-Z format to reveal a multitude of fascinating details - all the way from apples to zig-zags

- Explores stained glass by themes, patterns, designs and effects

- Requires no previous historical, artistic or religious knowledge

- Covers all the major periods and styles, from medieval to modern, Victorian to postwar, eighteenth century to Arts and Crafts, figurative to abstract

- Examines the fascinating and evolving iconography of stained glass

- Makes looking at gloriously colourful, artistically important windows both entertaining and rewarding

- Features a list of the top 50 places to see outstanding examples

- Offers a useful index of churches by county

The magical qualities of stained glass have an enduring appeal, but church windows tend to be ignored as a form of creative and artistic expression. Yet churches are accessible treasure trove of history, art and craftsmanship. No other set of historic buildings with such superb and important architectural and artists assets is as easy to visit. How to Look at Stained Glass is the companion guide that's needed to make sense of and enjoy the vast array of stained-glass windows in the churches of England.

This fresh, unstuffy guide:

- Uses an A-Z format to reveal a multitude of fascinating details - all the way from apples to zig-zags

- Explores stained glass by themes, patterns, designs and effects

- Requires no previous historical, artistic or religious knowledge

- Covers all the major periods and styles, from medieval to modern, Victorian to postwar, eighteenth century to Arts and Crafts, figurative to abstract

- Examines the fascinating and evolving iconography of stained glass

- Makes looking at gloriously colourful, artistically important windows both entertaining and rewarding

- Features a list of the top 50 places to see outstanding examples

- Offers a useful index of churches by county

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How to Look at Stained Glass by Jane Brocket in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A–Z OF STAINED GLASS

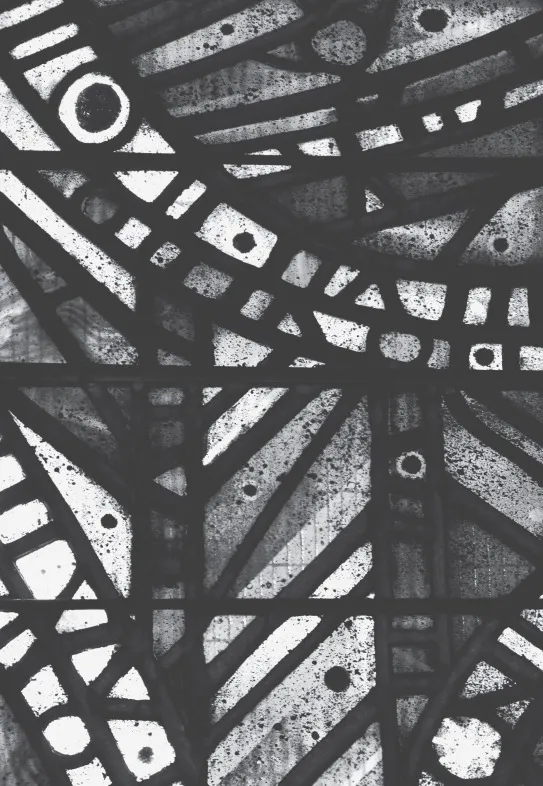

ABSTRACT

Abstract stained glass in a church can be challenging. In a place where people are looking for meaning, it does not offer any immediate answers or guidance. And yet it can be powerful, subtle, persuasive and awe-inspiring, while its meaning, if any, remains open to interpretation by each and every viewer. This is what makes abstract windows in churches exciting, demanding and intriguing.

Although deliberately abstract windows became popular in the postwar era, abstraction goes back a long way. I suspect that much pictorial stained glass from medieval times onwards becomes abstract when seen through failing eyes or from a distant pew, and without aids such as spectacles, lenses and binoculars: all that is discerned is the play of colour and light, blocks and shapes, and black lines, while the details blur and become indistinct. And although it is sometimes claimed that the innovative, rule-breaking 1915 West Window in St Mary, Slough, designed by the post-impressionist artist Alfred Wolmark (1877–1961), is the sole forerunner of abstract glass, there are plenty of examples of simple shapes and abstraction in medieval, Victorian and Arts and Crafts windows. The latter often contain beautiful abstract sections of thick, streaky or slab glass and innovative, organic lines of leading. Indeed, much background glass in pictorial windows of all periods is made up of abstract designs and, if you focus and crop, so to speak, you can find all sorts of stunning, colourful and stimulating patterns in churches.

2. Detail of east window, by Keith New, 1966. All Saints, Branston.

Wolmark’s window did mark a turning point in stained-glass design, but the sea change towards abstraction as an artistic choice did not take place until after World War II. Abstract stained glass might have emerged much earlier if the post-World War I period had not been dominated by the manufacture of traditional, conventional memorial windows to the fallen. By 1945, though, the time was ripe for Modernist, abstract windows which were very much in tune with what was happening in fine art, galleries and, of course, art schools, where many young stained-glass makers were being taught and were experimenting with the medium. Out went war heroes dressed up in medieval suits of armour, and in came a very new type of window which reflected the church’s changing role in postwar society, born out of its desire to become more modern and relevant. As a result, abstraction flourished alongside representations of ordinary people and everyday life, sometimes in the same window.

There is also the middle ground of semi-abstraction, in which highly stylised motifs, faces and body parts are half hidden in cleverly painted windows. Marc Chagall’s renowned windows in All Saints, Tudeley, contain fluttering butterflies and small creatures amidst abstract swirls of colour and lines. In the superb series by Tony Hollaway in Manchester Cathedral (some of the best abstract/semi-abstract glass to be seen from the 1970s to the 1990s), letters, foliage and fragments of rooftops can be made out, and the closer you look in order to make out the details, the more you see of the qualities of the glass itself, with its bubbles and cherished imperfections. The best known of all semi-abstract glass, though, is that in Coventry Cathedral (1962), designed and made by three of the biggest postwar names: Lawrence Lee, Keith New (1926–2012) and Geoffrey Clarke, who were directly inspired by Wolmark’s window.

Soon after these windows were made, however, purely abstract glass gained greater acceptance, and if anyone needs confirmation of its magical and uplifting properties, I recommend standing in front of John Piper and Patrick Reyntiens’ enormous and utterly beautiful baptistery window, also in Coventry, in which every one of the 195 panels is a miniature work of art. Piper understood that much of the effect of stained glass comes simply from the basic combination of colour, light, paint and lead lines, and that abstraction reduces a window to these essential qualities without losing its power to move and inspire awe. Abstract glass was also made from the 1950s onwards using thick glass and dalle de verre (see separate entry), particularly for new Roman Catholic churches and cathedrals. Outstanding examples include windows by Dom Charles Norris in Buckfast Abbey; by Gabriel Loire in St Richard RC, Chichester; by Henry Haig in Clifton RC Cathedral; and by Margaret Traherne, whose beautifully made, calm designs can be found in Coventry and Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedrals.

See also DALLE DE VERRE, LEAD, PINK, TEXTILES

ACTS OF MERCY

With so much Victorian stained glass in English churches, there is sometimes no getting away from expressions of that period’s piety in windows that can appear preachy, sententious and didactic to modern eyes. But it would be wrong to write off the more moralising examples completely; amongst them are numerous fine Acts of Mercy (or Corporal Works of Mercy) windows which illustrate examples of charity and sincerity. Despite some heavy-handedness – and frequently patronising attitudes – these windows are still as relevant as ever.

The Bible lists seven Acts of Mercy: to feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, clothe the naked, visit the sick, visit prisoners, shelter strangers and to bury the dead, although very often the last one is not illustrated (although there is an excellent 1857 example by Clayton & Bell in Holy Trinity, Blatherwycke). In addition to windows which include some or all of the acts, there are also plenty of illustrations of individual charitable acts and people, who may be biblical (e.g. the Good Samaritan), famous (e.g. Josephine Butler, Elizabeth Fry), saintly (e.g. St Elisabeth of Hungary), or simply ordinary and anonymous. With their collections of separate tableaux or vignettes, windows on the theme of mercy are easy to recognise and read. There is a great deal of pleasure to be had from examining how designers and artists have interpreted the different acts and reworked them for contemporary audiences, often with local references and modern touches. I particularly enjoy sickroom interiors and have spotted grand four-poster beds, rich drapes, piles of pillows, vases of flowers, potted plants, bedside tables with jugs of water and glasses and, at All Saints, Cambridge, an invalid with a bandaged head wearing a terribly smart emerald-green dressing gown with quilted satin collar and cuffs (Douglas Strachan, 1944).

3. Detail from Acts of Mercy scenes, designed by T. W. Camm, made by Messrs R. W. Winfield, 1883. St Mary, Wirksworth.

Every period has outstanding examples of the genre, and it is a great pity that more early windows, like that in All Saints in North Street, York, have not survived, because they would have said a great deal about the way communities have looked after the sick, poor and needy. Made around 1410, it is a memorial to Nicholas Blackburn, merchant and mayor of York, who is perhaps the bearded, compassionate-looking man cheerfully doling out bread buns from a huge wicker basket and releasing three men from the stocks as they wiggle their bare feet and toes. Equally rare and also very much of its time is Abraham van Linge’s colourful painted-glass Acts of Mercy window (c.1630s) in All Saints, Messing, which is reminiscent of a Brueghel painting, full of action and crowds looking on with vivid gestures and expressions.

These examples feature men, but in fact Acts of Mercy windows are one of the few types in which women predominate and are notably active. They embody many Christian virtues, and even though their gendered ideals of piety may no longer be acceptable, these windows can be fascinating period pieces. At St Mary, Wirksworth, the gloriously sumptuous 1883 window designed by T. W. Camm of Smethwick is a detailed evocation of charity as performed by gracious, well-to-do ladies. The scenes, with many lovely domestic details (potted fern, wicker basket of blue grapes and vine leaves, ruby-and-white flashed-glass tumbler), must have been a long way from the stark reality of the local Derbyshire mill workers’ and miners’ lives, and very much exemplify and embody the Victorian social hierarchy of philanthropy. It also contains one fascinating piece of local history, in the shape of a pineapple on a platter of hothouse fruit carried by the woman who is feeding the hungry: Joseph Paxton’s pineries at nearby Chatsworth House were some of the finest in Britain and the pineapples grown there were renowned in the nineteenth century. To give away a pineapple must have been the height of charity for the well-to-do of Wirksworth.

The best twentieth-century versions can be equally wonderful and revealing when updated to include the roles of the postwar welfare state and the National Health Service. Harry Harvey’s 1967 Acts of Mercy window in Sheffield Cathedral contains vignettes through the ages. For example, a hungry boy, perhaps in an orphanage, waits like Oliver Twist for his slices of ham and bread, while this time the sickbed is moved to an NHS hospital ward, complete with standard-issue bedside locker, and the visitor, bunch of flowers in hand, wears a sensible coat, Mary Whitehouse-style hat and cat’s-eye glasses.

See also BASKETS, FLOWERS

ANGELS AND ARCHANGELS

ANGELS

Angels are everywhere in stained glass. They are one of the mainstays of the art, so ubiquitous and obvious a subject that it is easy to take them for granted. But it pays to notice them – even if you are not an enthusiastic angelologist or believer in angels – because artists and designers often pull out all the stops to make them remarkable, dramatic, decorative, strange, sweet, sentimental, theatrical and camp. They reflect contemporary styles in art and design from medieval to modern, and are therefore an excellent subject for ‘compare and contrast’ exercises. Indeed, a newcomer to looking at stained glass would do well to begin with angels precisely because there are so many of them, they illustrate all aspects of designing and making, and they present a fabulous range of colours, patterns, faces, bodies, clothes, haloes and wings.

Fortunately, you can enjoy these windows without knowing the complex details of the various orders or choirs of angels. There are disputed versions of the hierarchy and no single agreed set of categories apart from the top-order archangels (see below), and even the attributes of two of the best-known types – seraphim and cherubim – often overlap and cannot be ascribed definitively. As a result, it may be more productive to focus less on identification of type and more on angels as a springboard for an artist’s or designer’s imagination.

The task of imagining what form a flying heavenly messenger might take has long exercised artists’ creative powers, and it is of course their wings that set them apart from mortals, so these are worth looking at carefully. There is staggering variation in size, span, shape, colour and feathers. Some cover the body like a bird costume or a ballet dancer in Swan Lake; medieval versions of six-winged seraphim are particularly good, as are those done by Victorian firms and C. E. Kempe, although it can be disconcerting when they have no feet–almost as unnerving as the cherubs, which are made up of just a childlike face and a small pair of wings floating above a scene, or in the tracery.

Many artists in the Arts and Crafts period went wild with their angels’ wings. Exaggeratedly large and extravagant versions can be found in windows by Edward Burne-Jones, Henry Holiday, Christopher Whall and Louis Davis, who used gorgeous colours (coral, magenta, sapphire, gunmetal blue, scarlet) to make them even more spectacular, while Karl Parsons goes one step further with his bright, multicoloured, almost neon-rainbow wings, and C. E. Kempe introduced peacock feathers into his. They were followed in the twentieth century by artists in the paler, more ascetic Sir Ninian Comper and Geoffrey Webb mode, who preferred smaller, less flamboyant green, gold, royal blue and purple wings to coordinate with angels’ outfits. Douglas Strachan (1875–1950), though, counteracts this politeness and asexuality with his unique, Cubist/Vorticist/Art Decoinfluenced, ultra-masculine, sci-fi warrior angels, which can be seen in places like the church of St Thomas and St Richard in Winchelsea (1929–33). Later, in the postwar period, many designers brought in a less lush, more modern, stylised aesthetic which echoes the textile and graphic designs of the period. The best are by Harry Stammers, Harry Harvey, Trena Cox and L. C. Evetts.

Angels often have typically angelic faces: childlike countenances with sweet expressions and clouds of golden hair. Some of the most appealing were made in the interwar years and look just like children’s book characters such as Milly-Molly-Mandy and friends (look for young angels by Veronica Whall, M. E. A. Rope and Margaret Rope). But there are also many other types of faces: some are gentle and maternal, or youthful and handsome, just as you might expect.

In the twentieth century there is no getting away from the campness of angels. Sir Ninian Comper (1864–1960) and Hugh Easton (1906–65) in particular specialised in wonderfully kitsch angels whose beautiful faces, bare bodies, defined muscles, blonde hair, spectacular golden wings and sheer glamour cannot fail to attract attention. At St Wilfrid, Cantley, Comper created a fabulous window in 1918 illustrating nine orders of angels, three of each set out in a three-by-three grid like a box of chocolates, forcing you to choose your favourite, while Hugh Easton’s best angels can be seen in the 1947 Battle of Britain window in Westminster Abbey and in the Royal Air Force Chapel at Biggin Hill (1955).

The sheer theatricality of angels means that groups and choirs can look stunning, especially in Te Deum windows, where they are often choreographed in circles or rows, their faces upturned and bathed in light, their wings forming intricate and elaborate repeat patterns like a corps de ballet or a Busby Berkeley dance scene. There is a lovely version in St Mary the Virgin, Battle (Burlison & Grylls, 1906), where there are also whole orchestras of musical angels flitting about, often in the higher reaches of windows or in the tracery, playing the most enormous range of instruments, many of which are not easily identified these days. In the Beauchamp Chapel in the Collegiate Church of St Mary, Warwick, 22 different instruments are played by 32 medieval angels, and Edward Burne-Jones filled the tracery of his 1875 window in St Martin in the Bull Ring, Birmingham, with charming musical angels.

ARCHANGELS

Archangels are regarded as the highest class of angels, the powerful guardians and messengers sent by God to perform specific roles, the closest thing to comic-book superheroes we are likely to find in windows and possibly the easiest angels for contemporary and/or non-religious viewers to understand and appreciate.

They are the subjects of some of the biggest set-piece designs and come with well-known narratives and symbols, so it is to the credit of numerous artists and designers that they have continually exploited the vast range of visual possibilities they provide and found new and expressive ways of depicting them in stained glass. An archangel may be old, grizzled and bearded or young, gentle and calm; he may be undeniably pretty, youthful and androgynous or strong-jawed, muscular and fierce; or he may even have the incongruous facial features of the fallen soldier whom he commemorates in a memorial window. As for clothes, wings, haloes and expressions, archangels are always rich sources of wonderful detail.

Although there are several archangels – the figure is often set at seven – English church windows usually contain just three (Michael, Gabriel and Raphael), sometimes four (add Uriel), and very occasionally five, as in the 1920 window by C. E. Kem...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Exploring a Church

- How a Stained-Glass Window Is Made

- A–Z of Stained Glass

- 50 Places to See Stained Glass

- Further Reading

- List of Images

- Index of Churches

- eCopyright