![]()

CHAPTER 1

IN THE LAND WHERE

TOMORROW WAS ALREADY

YESTERDAY

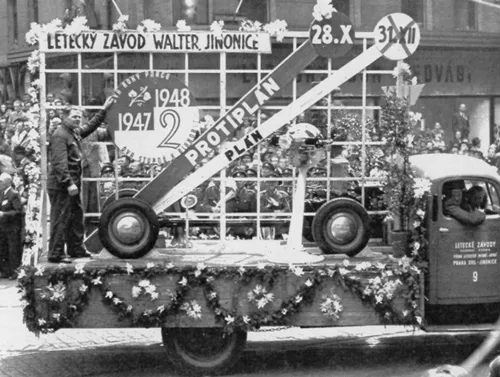

In May 1948 the aircraft manufacturer Walter, based in Jinonice, near Prague, committed itself to fulfilling its annual production target by 28 October, two months ahead of schedule (Figure 1.1). Although this desire to accelerate production can be understood in the context of general enthusiasm for the construction of socialism in the postwar period, such resolutions continued to be made even when the euphoria of the newly created people's democracies had long since given way to mundane routine. For instance, in 1957 a master miner, Spurný de Karviná, led a team that pledged to beat its coal extraction target by 3,000 tons. A month before the deadline, the team promised to go beyond this initial promise and produce a further 1,500 tons of coal.1 Similarly, in the run-up to 1 May 1958, some 120 work teams across the country promised to exceed their targets, and instead of saving 263,000 crowns in raw material they decided to save 804,000 crowns.2 At the Cooperatives Convention in 1961, a mass movement was launched to help agriculture catch up with industry and fulfil the objectives of the third Five-Year Plan (1960–5) within four years – echoing a commitment that had been made in 1949 as part of the first Five-Year Plan.3 In all, 84 per cent of cooperatives and 95 per cent of state farms answered the call. As for the machine industry sector, it was set the task of achieving the objectives of its so-called Five-Year Plans in just 21 months! This ‘patriotic movement’, as it was termed by the official Party newspaper Rudé právo, made a ‘decisive contribution to the building of a developed socialist society’.4

Figure 1.1 Float belonging to the aircraft manufacturer Walter, May 1948.

What was the meaning of this race against the clock, this desire to harness time? The fact that the above examples are by no means unusual makes this question all the more important. Similar scenarios can be identified in other Eastern European countries and even in Yugoslavia, which was then at odds with Moscow.5 To paraphrase the title of a famous collection of essays by Július Fučík, a member of the Czech communist resistance who was shot by the Nazis in 1943, it seemed that in these countries ‘tomorrow is already yesterday’.6

These examples illustrate the people's democracies’ determination to forge a new relationship between production and time. Altering the notion of linear time was an essential component of their new social project, bound up with the idea of economic progress and the attainment of an affluent society. In order to highlight this relationship, some historians have suggested that such regimes operated a ‘time economy’.7

In the postwar period Central and Eastern European countries underwent large-scale industrialisation. They strove to regain pre-war levels of development, to re-establish discipline in the workplace and to guarantee a decent standard of living for their populations. The spirit and objectives of reconstruction were therefore close to those of Western countries: they were based on a certain faith in progress and on developing the productive and spiritual strength of the community.8 In the East, however, discussing reconstruction plans provided an opportunity to test specific procedures: increasing production by calling on the heroism of the worker, accelerating production rates and reducing the time needed to attain objectives. This resulted in the pairing of an efficiency drive – in which every unit of time had to be used in the most productive manner possible, given the available resources – with a desire to reorganise production in order to control and accelerate progress by establishing objectives and then exceeding them. Plans for constructing socialism in the 1940s pursued these ideas, giving rise to a new structure of linear time.

The history of this temporal structure is the subject of this chapter. First, there is the question of its origins. As we will see, the notion of linear time deployed by the people's democracies is closely linked to that trialled by the Soviet Union from the end of the 1920s as part of the first Five-Year Plan (1928–32). Studying this link from the perspective of postwar Czechoslovakia raises the question of how – and whether – this temporal structure, devised in the very different context of pre-war USSR, could be adapted to a relatively developed country. When the war ended, Czechoslovakia (excepting Slovakia) and the GDR were almost as developed as Western industrialised countries. These two countries were thus exceptions in Central and Eastern Europe. To unwind the thread of this story, we need to go back in time to the moment when World War II ended, and gain a sense of what was at stake in the debate over reconstruction, from which the new concept of linear time would emerge.

This new time structure needed agents to implement it: the plan would provide a new, scientific organisation of production and socialist competition, and this socialist competition would ensure unprecedented discipline in the workplace. In order to understand how this new temporality modified the economy and the performance of its various actors – both human (workers and managers) and institutional (businesses) – we will focus on the period of reconstruction (1945–8) and especially on the first Five-Year Plan (1949–53). It was during these years that the new structure of linear time was deployed and that the first problems in its implementation appeared.

One issue was simultaneously the main objective and the main difficulty for the people's democracies: making the new linear time structure a routine concept, and perpetuating the virtuous circle of economic progress that this new structure was intended to engender. Did the Central and Eastern European regimes succeed in realising this aim? Did making this new temporal framework routine result in the birth of a specific socialist temporal culture? To answer these questions, we will follow its progress up to the immediate aftermath of the Prague Spring, when the intervention of Warsaw Pact armies brought reform to a sudden end.

The case study of one particular business – Českomoravská Kolben-Daněk (ČKD) – will be central to our analysis of these questions.9 In its glory days in the 1950s ČKD was the country's largest heavy-industry business, with nearly 50,000 employees, making it one of the world's biggest tram manufacturers. Created in 1927 by the merger of Českomoravská-Kolben and Breitfeld-Daněk, the business quickly specialised in the production of heavy-industry equipment, such as electric motors, cranes and compressors. Before World War II it shifted production to military equipment, and continued with this under German occupation. In 1945 the business was nationalised and returned to manufacturing trains, locomotives and, later, trams, mainly for the Eastern European market.10

A New Horizon for a New Society

Linear time structures society and gives it direction. It impinges on all aspects of society and all human activity taking place within it. It is, therefore, difficult to modify: any change to this temporal structure is influenced by changes in other social structures that are attached to it. It cannot be transformed unless the old social structures are destroyed or at least weakened, and unless there is an overwhelming desire for change. These two conditions coincided in Central and Eastern Europe after 1945.

Rewriting the social contract

The Polish partisan Dobranski, hero of Romain Gary's novel A European Education (1945), cherishes a dream throughout the war: that of a ‘new, happy world, a world in which doubt and fear would be banished for ever’.11 Through this fiction, Gary expresses the immense hope for change that was nourished and developed from 1943, when the war began to turn in the Allies’ favour. One question began to arise more insistently from this moment: on what foundations should reconstruction take place, and what should be its starting point?

Since the 1930s, Central and Eastern Europe had undergone a series of upheavals that resulted in an irreversible break with the past. Parliamentary democracies were gradually replaced by extreme-right nationalist and authoritarian regimes. Countries were gripped by waves of xenophobia and territorial revisionism that threatened the very existence of nation states. The economic crisis of the 1930s demonstrated liberal capitalism's inability to tackle deepening social inequality and the rise of extremes. World War II, with its successive occupations, expulsions, deportations and exterminations of civilian populations, brought about human and material devastation on a scale never previously seen in the region, and far more severe than that experienced in Western Europe. Nearly one in five people, mostly civilians, did not survive the war in Poland, with a particularly high death toll among educated people, who were targeted by both the Nazis and the Soviets. The death rates were 1 in 8 in Yugoslavia, 1 in 11 in the USSR and 1 in 15 in Germany, compared to 1 in 77 in France and 1 in 125 in the United Kingdom. The losses were less dramatic in other countries in the region, but still higher in percentage terms than in the West. For example, 4.4 per cent of Hungary's population died, as did 3.4 per cent of Romania's.12 The war meant that Eastern Europe fell even further behind the West in terms of development.13 In the East, much more than in the West, people's experience of the war was cataclysmic, and the conflict brought about a complete economic, social and political collapse: everything had to be rebuilt, frequently from nothing.14

In Central and Eastern Europe, as in the West, the war and the economic crisis popularised social projects aimed at rebuilding fairer, more egalitarian and more humane communities. Moreover, again like the West, the East no longer perceived responsibility for remedying social inequality as falling to specific groups (the neighbourhood, the family, religious communities or corporations) but to society as a whole, through state action. But the ruptures of the 1930s pushed this logic further than in the West, and the scale of the war's devastation made it impossible to envisage any viable alternative to a dirigiste economy. Agricultural reforms and nationalisation carried out shortly after the end of the war, sometimes even before the communists had come to power, ensured that the State dominated economic and social life.15 Such changes also enabled the establishment of a strong public sector and policies whereby social redistribution was carried out by the State, giving it the means to lay the foundations of a radically different social project.

How did the question of time fit into these processes? The very notion of planning implies faith in society's ability to foresee a certain level of development and to attain it according to the conditions set out in the plan. This forecasting mechanism contains the implicit idea that time may be mastered, and seen as a line leading society from one point to the next, and thus towards future progress. This faith in progress, which is typical of all modern societies, began in the Renaissance and was pursued during the Enlightenment. Ever since the Industrial Revolution, scientific and technical development has allowed people to believe in ever-greater control of progress, and thus of the passage of time. The capitalist production system known as the ‘factory system’ rests on the idea of optimising every stage of production by improving manufacturing methods, installing precise work schedules and decent salaries for workers (Taylorism), and following the principles of division of labour and standardisation (Fordism).16 This rationalised time management is one of the key characteristics of modernity. It implies a clearer separation of work time and leisure time, enables increased productivity and creates a timetable whereby each activity takes a precise and measurable amount of time.17

The history of Central and Eastern Europe after 1945 is the inevitable next episode in this story: large-scale planning brought this faith in controlling progress and time to a climax. The Czechoslovakian example allows us to understand the beginnings of this enterprise, its implications and what was at stake. Two periods, each with its own processes and objectives, are particularly relevant: the two-year Reconstruction Plan (1947–8) and the first Five-Year Plan, also known as the ‘Plan for Building Socialism’ (1949–53).

In pursuit of the Taylorian cycle: the Reconstruction Plan

In 1945 Czechoslovakia found itself in a unique position among its neighbours. Democracy had funtioned relatively well there in the interwar years, but collapsed in 1938 in the space of a few months. Hitler's dismantling of the country, undertaken with French and British consent, left an indelible mark on people's minds and delegitimised parliamentary democracy. The country was hit hard by the Great Depression, as were developed and industrialised countries in Western Europe. Around 1933 Czechoslovakia's industrial production barely reached 40 per cent of its pre-crisis level, and there were a million unemployed people in a population of 14 million. The State introduced protectionist and stimulus policies from 1933 onwards and these soon began to bear fruit. However, Czechoslovakia's progressive integration into the German economic space (Grossraumwirtschaft) and the outbreak of war changed the situation.18 It is true that Slovakia and the regions of Bohemia and Moravia did not experience military operations until the final months of the war: their economies were useful for the German war effort, so their industries were maintained and even improved, especially during the first five years of the conflict. Nevertheless, the end of the war was devastating for Czechoslovakia. Overall, it lost 3.7 per cent of its population and much of its industrial equipment. The damage caused between 1938 and 1945 corresponded to the national production of the six years leading up to the war.19 In 1937 Czechoslovakia was almost as developed as Belgium or the Netherlands, but by 1945 it was lagging behind developed European countries that had previously been its equals.

The question of how, and on what basis, reconstruction should happen was much the same in Czechoslovakia and other Central and Eastern European countries. The stakes were raised by the fact that the consequences of falling behind Western Europe went far beyond economic issues: there was the danger of becoming dependent on other countries, and of a return to the social, political and military instability that the region had only recently overcome. The war years and the occupation also had disastrous effects on workplace discipline: the processes of Aryanisation and Germanisation encouraged dilettant...