![]()

1

A Brief History of the Film Studios

Film industries in Latin America were collectively launched as part of a worldwide process in which representatives of the Lumière brothers distributed moving pictures by dispatching teams on planned itineraries designed to shore up the fascination which the new invention generated everywhere. Tasked with showing short films – either cheap amusements or filmed actualités – two teams went to Latin America: one was dispatched to Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo and Buenos Aires, while the other one went to Mexico and Havana (Chanan, 1996, 427). During the silent era, entrepreneurs (many of them immigrants from France, Germany and Italy) living in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and elsewhere tried their hand at creating their own films, typically filmed on the street and exhibited in itinerant roadshows. This chapter initially examines the development of modern movie studio facilities in the three largest film producing countries (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico). This is followed by a discussion of how the push to build studios in the contemporary era in some ways helped strengthen national film industries while incentivising foreign film shoots from abroad to film ‘runaway productions’ in Latin America. An exploration of socialist film studios in Venezuela and Cuba caps off the chapter.

The studio system came into existence in the 1920s during the silent era and transitioned to sound in the 1930s. This demarcation is significant because sound films based on national musical styles played a role in the success of the Argentine ¡Tango! (dir. José Moglia Barth, 1933) and Allá en el rancho grande (Out on the Big Ranch, dir. Fernando de Fuentes, 1936), a comedia ranchera (ranch comedy) featuring singing cowboys performing distinctly Mexican folk music. While Argentine and Mexican studios were privately funded, this was not always the case in Brazil. Well-known privately owned film studios Vera Cruz and Atlântida also relied on the state to help them in difficult financial times from the 1950s onwards (Dos Santos, 2009).

During this period, Latin American governments with the strongest economies (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico) passed various forms of legislation in support of the construction and maintenance of national film studios. To that end, screen quotas (mandatory time given to national films on screens) were enacted in Brazil as early as 1932. These measures were taken in response to the Hollywood studios’ growing dominance in Latin America and elsewhere, despite the temporary effects of the Great Depression on the US film industry.

PIONEERING STUDIO SYSTEMS

Brazil

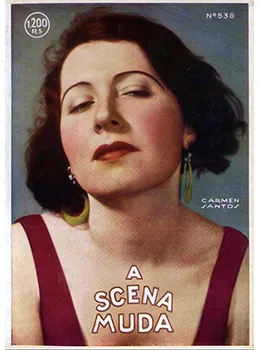

In the case of Brazil, two film studios established thanks to private capital in the early 1930s formed the nucleus of an industrial method of filmmaking that flourished up until the early 1960s. Entrepreneur Adhemar Gonzaga founded Cinédia Studios in Rio in 1930, and Carmen Santos followed suit by opening her Brasil Vita Filme in the same city three years later (King, 2000, 55). Cinédia was furnished with four sets of sound equipment, a studio large enough to accommodate several simultaneous productions, and two laboratories (de Usabel, 1982, 146). Cinédia would be known from this decade onwards as a producer of musical genre films called chanchadas, as well as carnival films, a subgenre that Carmen Miranda popularised worldwide beginning in the 1940s (de Usabel, 1982, 146). These films’ incorporation of the day’s popular musical stars from radio and theatre made them highly successful at the box office. Similar to the success of tango films, launched during the same period in Argentina, these films were an extension of the popular amusements to which working people had grown accustomed with the nickelodeon and vaudeville theatre (or, in the Latin American context, the theatre sketches known as sainetes). Cinédia Studios constitutes the first attempt at concentrated industrialisation in the history of Brazilian cinema (Johnson, 1987, 44). In 1933, Carmen Santos, the actor and producer who became a film studio owner, founded Brasil Fox Film Studios, a name which Twentieth Century Fox studio obliged her to change in 1935. It was renamed Brasil Vita Filme and became the second-largest studio in Brazil (Shaw and Dennison, 2007) and the first to be owned by a woman.

[Figure 1.1 Carmen Santos: actor, producer, film studio owner and pioneer.]

The two most important industrialised film studios during the 1940s were based in the two largest centres of commerce: Atlântida was constructed in Rio in 1941 and the Vera Cruz studio in 1949 in São Paulo. The latter was built during a period of rapid industrialisation in São Paulo; the city saw the creation of approximately twenty-nine companies between 1949 and 1953 (Schnitman, 1984, 57). The powerful industrial group Matarazzo invested massive amounts of money to create a studio they hoped would be capable of making quality films that were commercially successful, both domestically and abroad. They made use of imported European equipment, as well as personnel. Despite Vera Cruz’s short-lived boom, which produced such studio hit films as Oscar-winner O Cangaceiro (dir. Lima Barreto, 1953), its history serves as a cautionary tale about how a large studio can fail. The government support obtained by Brasil Vita Filme was insufficient to save it from bankruptcy, which it declared in 1954, due to the studio’s excessive investments in infrastructure and its inability to reach foreign markets (Johnson, 1987, 63). Atlântida, however, continued to make studio-style chanchadas until it closed in 1962. Its demise has been attributed mainly to changes in viewing habits due to the rise of television. Filmmaking in Brazil was revived from the late 1950s through the 1970s, but this revival yielded progressively political films, made independently outside the model defined by the studio system. As mentioned in the Introduction, Cinema Novo strove to expose socio-economic class disparities, racial inequalities and other ills that plagued society; it was part of the continent-wide, anti-imperialist movement known as New Latin American Cinema (see Introduction, Pick, 1993; Martin [ed.], 1997).

While commercial production waned with the rise of television, it ultimately resumed thanks to investment funding from powerful television conglomerates, with Rede Globo leading such initiatives. However, the Brazilian film industry was almost completely gutted in the mid-1990s when President Collor de Mello slashed all remaining funding with the closure of EMBRAFILME (the Brazilian Film Enterprise, founded in 1969) and CONACINE (the National Cinema Advisory Board, founded in 1982). As a result of these measures, production reached its lowest level yet, at three films in 1993 and four in 1994 (Johnson, 2007, 87). In response, two laws were passed, one in 1991 and the other in 1993, under a new administration that took over when Collor was impeached. The Rouanet Law and the Lei do Audiovisual (Audiovisual Law) offered tax incentives to large corporations that invested funds in national productions (mainly commercial films that might provide some return on investment). The Lei do Audiovisual also gave foreign film distributors in the country a chance to invest up to 70 per cent of their revenue in national film production (Johnson, 2007, 89). This law proved to be extremely successful at reviving film production, with the release of twenty-three films by 1998. Around the same time, the multimedia conglomerate Globo, which had created its film wing Globo Filmes in 1997, began to produce in earnest more commercial films in the new economic climate (Johnson, 2007, 95). Globo’s involvement stimulated interest among Hollywood majors to co-produce films; they eventually distributed seven Globo-produced films that reached over one million spectators (Johnson, 2007, 92). This relationship between the US movie studio cartel, the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and Globo is discussed in Chapter 3.

Mexico

The rise of the Mexican studio system was undoubtedly influenced by the Hollywood model of film industrialisation, but, as John King (2000, 42) points out, ‘North American styles and technical expertise would be alternately revered and reviled within Mexican cinema.’ This dominant influence mainly resulted from the fact that the personnel working on first studio films was comprised of production heads, actors and technicians who had all been trained in Hollywood before or while they worked in Mexico. While films had a similar look and form to their Hollywood counterparts, they were funded with national capital and the themes were typically home-grown.

Though films with sound had been introduced in the late 1920s in Mexico, the 1931 film Santa, directed by Spanish actor Antonio Moreno, was the first Mexican ‘talkie’ which synchronised image and sound on the same celluloid strip (García Riera in Gurza, 2001). The film was shot in a Hollywood style of continuity editing and was an exemplar of the familiar ‘fallen woman’ genre, but the narrative was based on a melodramatic Mexican novel written by Federico Gamboa. The lead actors, Lupita Tovar and Ernesto Guillen (who also went by the US stage name Donald Reed), had experience working in both silent and sound films in the United States. The film was set in a brothel and the narrative revolves around Santa, a young, innocent girl who falls into prostitution and lives a life of underworld dealings and vice – a life not of her own making. While the film was a popular box-office success, critics gave it mixed reviews. The crux of the debate was whether it was too closely tied to a Hollywood format or if it had its own merits as a Mexican film. Two critics at the magazine El Ilustrado lauded the effort that Santa represented but felt there was too much US imitation at play. While one reviewer acknowledged the advantage of gaining technical expertise and ‘commercial experience’ from abroad, he noted it should ‘avoid hewing too closely to the “standardised” products of Hollywood and instead make films … which interest all of Spanish America and Spain … films with American technique but Mexican substance’ (Jarvinen, 2012, 99). Santa marked a watershed year for production; six more films were produced, many of which used the same professionals who had worked on Santa or who had come from Spanish-language filmmaking in the United States (Jarvinen, 2012, 99).

These melodramatic films often employed popular music and folklore that were familiar in everyday life and became more popular with the advent of famous stars who sang their own renditions. Thus, productions such as Santa began a successful run of ‘cabaret’ films that lasted through the 1930s. The film Allá en el rancho grande later helped launch a wave of popularity for ranchera music in 1936. Indeed, the film landed Gabriel Figueroa (Emilio ‘El Indio’ Fernández’s famed cinematographer) a prize at the Venice Film Festival, and succeeded financially at home and abroad. In 1938, film was the second-largest industry in the country after oil (King, 2000, 47). This emphasis on the popular music of Mexico led to the formation a very successful film genre known as the comedia ranchera, which helped propel the Mexican film industry into a position of stability and provided an opportunity for growth. This, in part, paved the way for Mexico’s entrance into its famed ‘Golden Age’ of cinema, which began in the 1940s and ended around 1953.

Seth Fein notes that unlike the Hollywood studio system, Mexican studios were not controlled by single producers; instead, production companies rented services from studio operators (1994, 102). Some studios were privately owned and some were supported by the state. In 1935, for example, CLASA (Cinematográfico Latino Americana, SA) was furnished with the most up-to-date equipment and received subsidies from the Mexican government to foster a domestic cinema that could demonstrate national (or perhaps nationalistic) values (Noble, 2004, 14). Mexican Estudios Churubusco Azteca was founded in 1945 in an agreement between the Manuel Ávila Camacho government, RKO and Televisa.

Mexico’s movie studio system flourished during the 1940s and 1950s, when it was the largest film industry in Latin America. Seth Fein notes that, by the time Emilio Fernández’s critical success Río Escondido (Hidden River, 1948) was released, ‘movies represented Mexico’s third largest industry by 1947, employing 32,000 workers. Mexico had 72 producers of films, who invested 66 million pesos (approximately US $13 million) in filming motion pictures in 1946 and 1947, four active studios with 40 million pesos of invested capital, and national and international distributors’ (1994, 103).

Many scholars have focused on Mexico’s ‘Golden Age’ cinema due to the success and popularity of various auteurs, such as Emilio ‘El Indio’ Fernández, Spaniard Luis Buñuel, who made films in Mexico during this time, and other more commercial filmmakers such as Julio Bracho, Roberto Gavaldón and Ismael Rodríguez. Famous actors of the time included Cantinflas (Mario Moreno), María Félix, Dolores del Río, Lupe Vélez, Ramón Novarro, Jorge Negrete, Pedro Armendáriz, Pedro Infante and many others. Work by film historians Jorge Ayala Blanco (1968) and (1974), Emilio García Riera (1992), Carl M. Mora (2005), Charles Ramírez Berg (1992, 2015) and Andrea Noble (2004), as well auteur studies (Dolores Tierney, 2007, and Ernesto Acevedo-Muñoz, 2003), detail the effervescent period when Mexico’s cinemagoing culture flourished due to an industrially robust studio system that relied on support through private funding. Funds came from both national investments and the United States, which supported national film production as a bulwark against what they perceived to be communist infiltration in other Latin American film industries. While some critics might debate the term ‘Golden Age’, Noble notes that figures confirm that characterisation: production went from thirty-eight features in 1941 to eighty-two in 1945, reaching a record high of 123 in 1950 (2004, 15). This was also an age of transnational collaboration between the United States and its trusted ally, Mexico, in the ideological fight against communism. The Mexican ‘B’ film Dicen que soy comunista (They Say I’m a Communist, dir. Alejandro Galindo, 1951), among others, perpetuated Cold War propaganda (Fein, 2000, 93).

The special treatment that the Mexican film industry received from the United States in part explains why it flourished. According to Variety (written in its customarily choppy style), the desire to position Mexico as the most prolific and popular film producer in Latin America was no secret:

A terrific US pressure is being exerted to eliminate Argentina as the world’s greatest producer of Spanish-language films, and elevate Mexico into the spot. Action is part of the squeeze being exerted by this country to blast Argentina from its friendly attitude toward the Axis. Francis Alstock, film chief of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (OCIAA), is constantly in and out of Mexico helping the industry. WPB [War Production Board] has cracked down hard on the volume of raw stock being shipped to Argentina, and is lavish with Mexico. (Anon., 1943a)

In 1942, the Mexican film industry produced forty-nine films, and by 1944, its production had increased to seventy-eight. That same year, Argentina’s production slid down to twenty-four films, a more than 50 per cent decrease from its 1942 level of fifty-six (Schnitman, 1984, 88). In 1944, a film critic for Variety commented: ‘the WPB is still awaiting word from the State Department on what the 1944 quotas to the various countries should be. You will recall that about a year ago, the allotment for Argentina was cut back because of her flirting with the Axis and Mexico received a “super-colossal footage”’ (Lowe, 1944).

Reports stated that, rather than receive forty million feet of film from the United States, Argentina would receive 50 per cent less in 1943. This represented the deepest cut in Latin America. In contrast, Mexico would be ‘well taken care of’ (Anon., 1943b). An interdepartmental memo from the Motion Picture Division of the OCIAA explains the Hollywood film industry’s motivations for providing technical, material and financial aid to the Mexican film industry:

The fact is that Mexico will never be a competitor of the American companies no matter how much help is given to the Mexican industry. But if better Spanish speaking pictures were made through the help extended to the Mexican industry, it should result in larger audiences, new theatres, and a strong and better motion picture situation in Latin America. It should strongly stimulate and develop the market for American pictures. It should help them become more profitable. The American company which helps the most may reap the greatest benefit. (Bohan, 1942)

Other justifications were connected to tax incentives for Hollywood that neutralised the risk in investing in their Mexican counterparts. Finally, the author of this internal memo felt that the plan could potentially result ‘in developing Mexican talent, the best of which might be utilised in America’ (Bohan, 1942). Other OCIAA efforts to assist the Mexican film industry included donating film equipment to help build film studios. John Hay Whitney and Francis Alstock (both representatives of the OCIAA) stated in a memo that, in order to avoid a monopoly of film studios, the OCIAA would help ‘consolidate the interests of the Azteca and Stahl studios, and the other unit [was] to be the Clasa studios’. In addition, they committed to help set up a finance fund for Mexican motion pictures and promised to send Hollywood film experts to participate in training Mexican technicians. Finally, the OCIAA offered to ‘negotiate with the American Moving Picture industry for the commercial distribution of Mexican pictures in those countries and territories requested by the producers of the Mexican Committee’ that met with representatives of the OCIAA (Whitney and Alstock, 1942).

Film scholar Román Gubern (1971, 95) has also provided an explanation for why the United States aided the Mexican film industry – a measure that debilitated Argentina:

The OCIAA policy to favour the Mexican film industry has a double advantage from the point of view of United States interests. From an ideological perspective, an Allied country was a better guarantee of suitable motion picture content; from an economic point of view, reducing the importance of the Argentine film industry in Latin America spared North American film companies a competitor from some sectors of the Latin American film market, and it gave North American entrepreneurs the opportunity to participate in the development of the film industry in Mexico. For instance, in 1945, 49 per cent of the stock of Churubusco studios (the most important in Mexico in the 1940s) was owned by RKO.

Ultimately, it was a confluence of ideological and economic factors which caused the United States to take sides in supporting one Latin American country’s film industry over another.

The 1950s marked a decline in the number of quality films made in Mexico, when shooting was reduced from five to three weeks at a time to cut production costs and save money on the high wages that Mexican film stars were earning (Noble, 2004, 16). Along with other factors, this financial constraint contributed to the rise of rapidly made, inexpensive films that lacked artistic merit. These movies were known as ‘churros’, as Anne Rubenstein (2000, 665) notes: ‘like [the dessert fritter], [they] were not nourishing, rapidly made, soon forgotten, identical to one another and cheap’. Apart from a few exceptional films made during that period – Macario (dir. Roberto Gavaldón, 1960) and El ángel exterminador (The Exterminating Angel, dir. Luis Buñuel, 1962) – Mexican films failed to attract large numbers at the box office or to get exported abroad.

In t...