- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

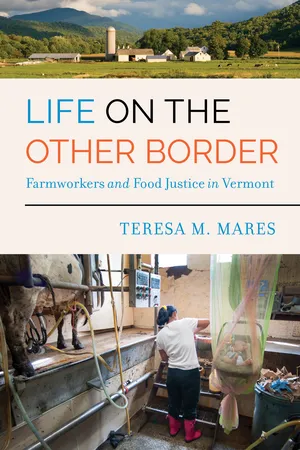

In her timely new book, Teresa M. Mares explores the intersections of structural vulnerability and food insecurity experienced by migrant farmworkers in the northeastern borderlands of the United States. Through ethnographic portraits of Latinx farmworkers who labor in Vermont’s dairy industry, Mares powerfully illuminates the complex and resilient ways workers sustain themselves and their families while also serving as the backbone of the state’s agricultural economy. In doing so, Life on the Other Border exposes how broader movements for food justice and labor rights play out in the agricultural sector, and powerfully points to the misaligned agriculture and immigration policies impacting our food system today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Life on the Other Border by Teresa M. Mares in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

Vulnerability and Visibility in the Northern Borderlands

I live in an apartment attached to the barn. I used to only leave the apartment to go to the milking parlor to help my husband sometimes. I never went outside. I didn’t see the sun.

SOFÍA

It’s a constant fear. . . . I always think when I see a car get stopped in front of me . . . what would happen if that were me? What could I do? If a car follows you for a long time, you always are thinking that it could be la migra. And what happens if all of a sudden they turned on their lights? So I’m always watching to see which car is behind me. And before I wasn’t afraid! I would go out as normal and I thought “Oh, here in Vermont? That won’t happen!” But even though you might struggle against it . . . there are things that are too strong.

GABRIELA

THE RURAL LANDSCAPE SURROUNDING the large dairy farm where Sofía and her husband Santiago lived and worked for more than eight years could easily provide the background for a Vermont tourism postcard. Red barns and grazing Holsteins punctuate the rolling green hills, and narrow state highways transect the countryside in a haphazard patchwork. Fewer than two miles south of the federal border separating northern Vermont from southern Quebec, Sofía and her family have come to see this region as home, albeit an impermanent one. As I make my way north to pay them a visit on a warm September day following the first hard freeze of the year, the radio abruptly switches from English to French and Vermont Public Radio is replaced by the early nineties tunes that seem to dominate Quebecois pop stations. Just a few moments before I arrive at their door, my cell phone announces with the now-predictable tone that I am roaming internationally, despite the fact that I am still firmly within U.S. territory.

As my primary field site, the landscape of this northern region of Vermont has become deeply familiar to me. After years of driving through this area, I anticipate the bends in the road and the occasional roadside stand selling “farm-fresh” eggs and maple syrup on my way to the dairies where Latinx farmworkers work two, sometimes three shifts each day. The smell of manure that clings to the air and permeates my hair and clothing is a signal that I am in the field—both intellectually and physically. The sounds of the rough transition from paved highways to the ruts of well-worn dirt roads indicate an increasing separation from the small city where I live, write, and teach. Despite the astounding beauty of this rural landscape, I can no longer separate these bucolic sounds, sights, and smells from the violence I know is embedded in industrial milk production.

For Sofía and Santiago, this countryside holds an even more complex and intimate set of meanings. Through our many conversations spanning four years, I learned that it is a place of economic opportunity, of isolation and loneliness, and of frequent and perhaps unexpected conviviality with the family who owns the farm. It is a place of ugliness and fear, but also a place of joy, since it is where they started their young family next to the milking barn where Santiago worked upwards of 70 hours every week. And until 2015, when Sofía returned to Mexico with her two young children, it was a place where the risks and dangers of living in the borderlands were all too real. Every single day they lived in Vermont, Sofía and Santiago grappled with three distinct manifestations of the border. The first is the boundary that surrounds the farm, bordering their private home space from the public space where their ethnicity and language mark them as outsiders in this overwhelmingly white state. The second is the federal border that divides the United States from Canada just a few miles north, the proximity of which is never forgotten given the frequency of Border Patrol vehicles passing by the farm. The third is the border they crossed from Mexico into the United States, a boundary that separates their new life as a family from their previous one as two young adults in love—the former a life of poverty but greater freedom.

Over the many visits I paid to Santiago and Sofía, I never made it past the small ten-by-ten-foot room that functioned as kitchen, dining room, play room, and living room. Bathed in cold florescent lights and always accompanied by the chatter of telenovelas and rowdy Mexican talk shows, the room was always immaculately clean—an impressive feat given that it was a mere twenty feet from the milking barn. This room was separated from the filth, but not the smells, of the milking barn by a series of doors sealing off the farm’s main office and a narrow hallway littered with manure-splattered muck boots and rain jackets. Off to the side of the hallway, there was a tiny bathroom adorned with bright pink Disney decorations, which I always found a bit too cheerful given the surroundings. I first met Sofía and Santiago in the summer of 2012, when their first child, Mia, was only about six months old. At this age, Mia was a bundle of chubby arms and legs, big brown eyes that always sparkled with mischief, and two tiny black pigtails sticking straight up in the air. As she grew, her bravery around giant bovines always impressed me, as did her mother’s love and devotion.

In this small, multi-purpose room, Sofía dominated our conversations—gossiping about our shared acquaintances, cajoling me about when I would get married and have children, and often sharing a homemade lunch or strawberry ice cream in the same shade of Disney pink. On the days that we enjoyed ice cream, I could not help but wonder if the main ingredient had come from this farm, or any of the others I have come to know from the inside out. As I came to learn, this small room was a haven for Sofía and Santiago, cozier than the dark bedrooms that I could glimpse in the interior, despite its sterile lighting and utilitarian decor. It was a space that bell hooks might call a “home-place,” offering their family somewhere to dwell and find familiarity. At the same time, this room functioned as a prison cell for Sofía and Santiago, who lived in continuous fear of the Border Patrol agents passing by the farm on a daily basis.

As a border state with an active presence of Immigration and Customs Enforcement personnel, many of the same fears, anxieties, and dangers that are endemic to the U.S.-Mexico border are reproduced in the state of Vermont. This brings with it embodied consequences for food security, diet-related health, and the mental well-being of migrant workers like Santiago and Sofía. In the post-9/11 era, scholars point to the ways that the U.S.-Canada border has become increasingly “Mexicanized” amidst concerns of terrorism and lax surveillance.1 While the dangers of the U.S. northern and southern borderlands are distinct in how they impact the individuals and families who transgress and reside within them, significant and persistent patterns of structural vulnerability and violence pervade the everyday lives of Latinx migrant farmworkers in Vermont. For these workers, these forms of vulnerability and violence are inextricable from the ongoing fear and anxieties of living and working in a border region where one is invisible in the workplace yet hypervisible in public.

This chapter continues with the framework of Bordering Visible Bodies introduced in the previous chapter through illuminating and investigating how bordering plays out in the structural vulnerabilities and violence that migrant farmworkers experience in a region where migration from Latin America is a newer phenomenon than in most other U.S. states dependent on agriculture. In doing so, this chapter moves the fields of Latinx studies and border studies into a new geographic and social space that has remained largely invisible in these fields of scholarship. As I examine Vermont’s iconic working landscape, I show how processes of racialization and labor exploitation exacerbated by the proximity of the border shape the experiences of Vermont’s farmworkers in distinct ways. This lays the groundwork for the following chapters, which explore how Latinx migrant workers sustain themselves and how these efforts are constrained by broader cultural, political, and economic forces.

BORDER VIOLENCE AND VULNERABILITY

Throughout their journeys, individuals like Sofía and Santiago transgress, reside within, and are constrained by political and cultural borders that simultaneously act upon them and are remade by their presence. As a conceptual category tied to multidimensional and continuously shifting geographic and social spaces and processes, borders have long been an important area of scholarship across the humanities and social sciences. In an ever-globalizing world, contemporary border theory has to contend with a central question: Are we moving toward a borderless world, characterized by flows and networks, or, are new forms of nationalism and xenophobia reinforcing territorial lines and often-violent defenses of state sovereignty? As Anssi Paasi argues, this is in reality a “both, and” question rather than an either-or dilemma.2

Calling for new approaches to studying borders in a dynamic world, Paasi emphasizes that we must explore how territoriality works in practice, rather than seeking to build a universal border theory. This demands that we examine not only the geographically specific and physical divisions of territories but also the processes of bordering that are intensified at these divisions and inevitably extend outwards to other geographies and inwards to the bodies and minds of border-crossers and border-dwellers. Tracing the development of border theory, Paasi states,

One important step has been the abandonment of the view of borders as mere lines and the notion of their location solely as the “edges” of spaces. This has helped to challenge strictly territorial approaches and to advance alternative spatial imaginations which suggest that the key issues are not the “lines” or “edges” themselves, or not even the events and processes occurring in these contexts but nonmobile and mobile social practices and discourses where borders—as processes, sets of sociocultural practices, symbols, institutions, and networks—are produced, reproduced, and transcended.3

The U.S.-Mexico border has long been a key sociospatial location for the study of borders. We owe a great debt to Gloria Anzaldúa for her work blurring these theoretical imperatives long before Paasi called for it. Yet as crucial as it is to examine the dividing line between the U.S. and Mexico for individuals like Sofía and Santiago who migrate between these two nations, I make the case in this chapter and those that follow that we must extend our analysis to the violent forms of bordering that follow these same individuals into other borderlands.

In the post-9/11 era, social scientists have been particularly active in pushing borderlands scholarship forward, engaging in dynamic conversations about how to best utilize the strengths of ethnography and other anthropological methods in a period when the borders of the nation-state are becoming more porous for the movement of capital and more impervious to the movement of people. The most relevant of these works to my own study are those that examine the violent forms of bordering that are unleashed against migrants—before, during, and long after the border crossing. Two scholars in particular, Seth Holmes and Jason de León, are recognized for their work in illustrating the contemporary forms of violence and suffering that persists along the U.S.-Mexico border and continue to shape the lives of migrants as they move across the United States. As I have considered the ways that crossing the southern borderlands and laboring in the northern borderlands shape the daily lives of migrant workers in Vermont, their analyses have proven useful as a starting point for my own work.

Both Holmes and De León draw upon theories of structural violence to examine the risks and dangers confronting immigrants making their way north to the United States. Their studies of violence build upon and extend the work of anthropologists including Paul Farmer (2005) and Nancy Scheper-Hughes (1992), who have engaged ethnographic methods in their efforts to demystify the social inequalities that pervade everyday life and decrease the life chances of the poor. While definitions of structural violence abound, I always find it useful to return to the following articulation by Paul Farmer, who describes structural violence as a

broad rubric that includes a host of offenses against human dignity: extreme and relative poverty, social inequalities ranging from racism to gender inequality, and the more spectacular forms of violence that are uncontestedly [sic] human rights abuses, some of them punishment for efforts to escape structural violence.4

In Farmer’s view, human suffering is structured by historic and economic factors that conspire to constrain agency. As both Holmes and De León show, long histories of poverty, systemic racism and classism, and dispossession of land and other natural resources are the foundations of the structural violence that both impels people to migrate from Latin America and shapes their lived realities in the United States.

In his ethnography Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies: Migrant Farmworkers in the United States, Seth Holmes offers a window into the lives of migrant farmworkers in U.S. agriculture. Through bringing his readers from Oaxaca, Mexico, across the U.S-Mexico border, and into the states of California and Washington, Holmes traces the transnational circuits of people that sustain large-scale berry farms and other sectors of industrial agriculture. As a trained physician, Holmes details the forms of structural violence and suffering that the Triqui (an indigenous group from Oaxaca) endure in both Mexico and the United States, and how the medical establishment largely fails them in both nations.

While the book’s opening sequence of migration, detention, and eventual release is attention-grabbing, for me it is Holmes’s analysis of how violence against mostly poor indigenous migrants is naturalized, normalized, and internalized that is the most instructive. With a nod to Paul Farmer’s work but also to Bourdieu’s theories of symbolic violence, Holmes examines how violence is enacted on the migrant body, underscoring how the industrial food system is quite literally built upon the backs of immigrants. Pointing to both the rampant racism in rural farming regions and the “subtle complicity of the dominated,” Holmes lays out how symbolic violence, or the “naturalization, including internalization, of social asymmetries,” enables the manifestation and embodiment of structural violence in premature death, sickness, and severe economic inequalities.5 He demonstrates with ethnographic detail how classed, raced, and gendered bodies located at different positions along the “ethnicity-citizenship hierarchy” are socially determined to be more or less worthy of respect, health care, and ultimately, living. The browner that body is, the more indigenous, or the extent to which a person is female determines how they are subjected to and experience violence.

In The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail, Jason de León presents an ex...

Table of contents

- Subvention

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 • Vulnerability and Visibility in the Northern Borderlands

- 2 • More than Money: Extending the Meanings and Methodologies of Farmworker Food Security

- 3 • Cultivating Food Sovereignty Where There Are Few Choices

- 4 • They Are Out, They Are Looking: Providing Goods and Services under Surveillance

- 5 • Resilience and Resistance in the Movement for Just Food and Work

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1: Semi-Structured Interview Guide for Farmworkers

- Appendix 2: Semi-Structured Interview Guide for Service Providers

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index