1.1 The morphology and phonology of Murrinhpatha

This book is a detailed study of morphological and phonological patterns in the Murrinhpatha language of northern Australia, and especially of how these two structural dimensions intersect. It is a study of how words are structured in this typologically interesting language.

The nature of words differs enormously among languages of the world, so much so that if we wish to use the concept ‘word’ in describing diverse languages we find that we must stretch its definition to cover a diverse range of linguistic phenomena. A word in Vietnamese (Austroasiatic) is a single syllable of lexical meaning (Schiering, Bickel, & Hildebrandt, 2010), while a word in Galo (Tibeto-Burman) almost always combines more than one monosyllabic morpheme by derivation or compounding (Post, 2009). In Cayuga (Iroquoian), a single lexical root can be deployed in hundreds of complex words that derive their meaning from that root (Sasse, 2002). German noun compounding very freely combines clusters of otherwise independent nouns into a single prosodic word, e.g. sée-alp-weg ‘mountain lake path’. Conversely, in Cree (Algonquian: Russell, 1999) a verb that is made up of highly interdependent subparts may be pronounced as a sequence of distinct prosodic word units, e.g. nikî-máci-pamihikónânak ‘they looked after us badly’ (Russell, 1999, p. 205). Cross-linguistically, a word is some kind minimal utterance where phonological structure (sound patterns) and morphological structure (meaningful sub-parts) intersect. But the nature of this intersection can be very different from language to language, and it has often been noted that ‘word’ is a rather elusive concept, for which linguists fail to agree on any clear definition (Bickel & Zúñiga, 2017; Bloomfield, 1933; Dixon, 2002b; Haspelmath, 2011). This book may be thought of as a study of words, but it does not propose any essential definition of ‘word’. As explained later in this chapter, I do not consider ‘word’ to be a principled natural category in Murrinhpatha, and this book could more accurately (and unmarketably) have been titled Patterns of sound and meaning in the more tightly dependent combinatoric structures of Murrinhpatha.

Polysynthetic languages, found throughout North America, the Arctic, the Caucasus and northern Australia, present varieties of ‘sentence-words’ in which many meaningful elements are strung together into a single, unbreakable unit of speech (Evans & Sasse, 2002). Polysynthetic languages have drawn much attention for their deviation from the more conventional concept of ‘word’, but to fully appreciate the nature of this deviation, we must carefully examine the interaction of morphological and phonological structures in these languages. This book presents such a study, for the Murrinhpatha language of northern Australia. The structure of words in Murrinhpatha, just as for Vietnamese or Galo, is quite unique, and deserving of sustained linguistic analysis. In fact Murrinhpatha word structures exhibit some characteristics that have not been described for any other language to the best of my knowledge.

In this chapter I first introduce the Murrinhpatha language, then introduce the concepts of morphology and phonology that underpin this book.

1.2 A brief sketch of Murrinhpatha

This book is not a general grammar of Murrinhpatha, but rather focuses on a more detailed analysis of morphology, phonology, and the interaction between the two. There is some discussion of phrase constituency (in particular, noun phrases and verb phrases), but only inasmuch as these are necessary to understand word structure (§4.3), or to define the domain of attachment for bound morphology (§7). ‘Higher level’ topics in syntax, semantics and pragmatics are not addressed (but see e.g. Blythe, 2009; Nordlinger, 2011b; Walsh, 1976). However, to provide some context as to how Murrinhpatha words fit into sentences, I here provide a brief grammatical sketch of both word and sentence phenomena.

Murrinhpatha has a fairly simple phoneme inventory, with four vowels and 22 consonants. Like most Australian languages, its consonants have an extensive range of place contrasts, but rather restricted manner contrasts. Syllables are CV(C)(C), and combine into monosyllabic or polysyllabic words. Prosodic prominence involves one pitch accent in each (short) phonological phrase, with the accent anchored to the penultimate syllable or monosyllable of the last word in the phrase (1–4). However, much of the bound morphology is excluded from the determination of accentual anchoring (5, 6).

| (1) | wák | ‘crow’ |

| (2) | pálŋun | ‘woman’ |

| (3) | kan̪̪t̪án̪in | ‘sweet’ |

| (4) | maɭuk múɳʈak | ‘old didgeridoo’ |

| (5) | lít̪ puɾ=ɻe | ‘with an axe’ |

| axe=INSTR | |

| (6) | púɾu-ŋime | ‘let’s go!’ |

| go.1INCL.IRR-PAUC.F | |

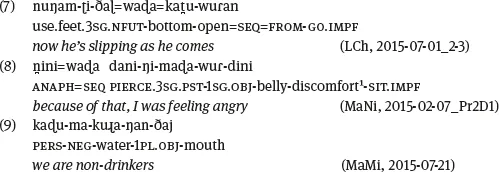

As mentioned in the previous section, Murrinhpatha words may have elaborate morphological structure. This is most common for verbs (7, 8), though nouns may also exhibit substantial complexity, especially when they play the predicating role in a clause (9). The details of these morphological structures are the main subject matter of this book.

While the configurations of morphological structure within the verb are particularly elaborate, there are only simple configurational structures at the phrase level. There is a clear noun phrase structure of the [head modifier+] type (10), and a verb phrase of the form [NEG coverb verb] (11). Note that object or other argument NPs are not included in the configurational verb phrase.

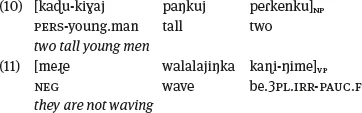

A single preposition /ŋaɾa/ can introduce either a locative NP (12) or a relative clause (13), although relative clause relations are more often simply implied by parataxis (14) (Walsh, 1976, p. 287ff.).

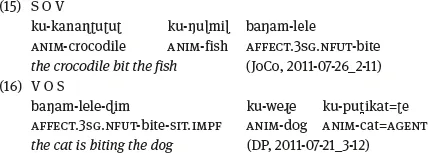

Other than these NP, VP and PP/REL structures, no other configurational phrase structures have been observed in Murrinhpatha. SOV and SV are the most frequent word orders for uncontextualised declarative sentences (i.e. not taking into account discursive context), though research on this topic is at an early stage (Mujkic, 2013, p. 56; Walsh, 1976, p. 276ff.). Other orders are also acceptable (15, 16), and in practice one or more arguments are generally elided, or dislocated into separate intonational units.

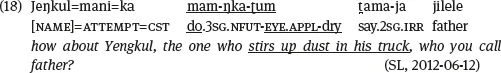

While (16) uses an agentive enclitic to distinguish thematic roles (see §7.3 for other such case markers), explicit NP role marking of this type is in fact rather rare. It is more common for sentences to use overt nominal arguments for only a subset of the participants, and for their roles to be contextually understood, as in (15) above. Only high-animacy participants (humans, and sometimes animals) are marked on the verb using pronominal morphology. But verbs have a tendency to specify not just events but entities, sometimes obviating the need for nominal arguments (17, 18).

Verbal morphology marks three syntactic categories of pronominals: subject, direct object and oblique. Direct objects are unmarked for third singular, and obliques are in competition with direct objects for a single morphological slot, with free variation as to which pronominal marker should win out (Bill Forshaw, p.c.).2 The system of grammatical number is rather complicated, with singular, dual, paucal and plural at the maximal level of distinction, and category mergers occurring among the non-singular types in various grammatical contexts (§6.2). Free and bound pronouns also have special forms to distinguish groups of people who are siblings in the system of kinship classification (Blythe, 2013; Walsh, 1976, p. 151ff.).

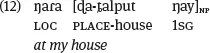

Both the nominal and verbal parts of the lexicon are dominated by compound forms, which are discussed extensively in this book. For nominals this most prominently involves a set of 10 nouns that have very broad meanings, and combine with other nominal lexemes that provide more specificity, typically in a hypernym–hyponym relationship (19, 20). The 10 nouns used as heads of compounds in this way can be labelled ‘classifier nouns’, because they can be seen as ‘classifying’ the nominal lexicon into semantic categories (Walsh, 1997). In previous work on Murrinhpatha the classifier nouns are written as separate words, but in this book they are treated as parts of compound words, based on prosodic evidence.

| (19) | ku-walet |

| animate-fruitbat |

| (20) | mi-kileɳ |

| vegetable-green.plum |

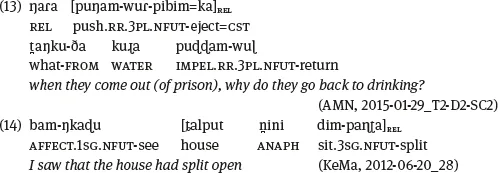

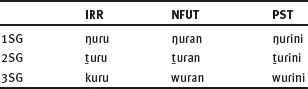

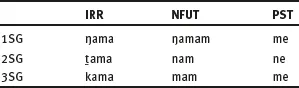

For verbs there are 39 finite verb stems, each of which appears in a paradigm of 42 inflected forms. The inflectional patterns of these paradigms are highly irregular. Fragments of two verb stem paradigms are shown in Tables 1.1 and 1.2.

Table 1.1: Fragment of the verb stem paradigm /ɾu/ ‘go’.

Table 1.2: Fragment of the verb stem paradigm /ma/ ‘say, do’.

Some finite verb stems (including the two below) can be used as simple verbs, but most are compounded with coverbs to produce more specific predicates.

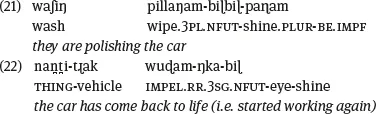

Coverbs are an open lexical class, though there are limits on the productivity of verb-coverb compounding (21). There may in addition be recursive compounding of a body part nominal with the coverb, modifying the predicate by specifying an affected body part or various metaphorical extensions thereof (22).

The finite verb stems vary from those that make a clear lexico-semantic contribution to predicates, to those that contribute more grammaticalised valency or aktionsart cont...