![]()

III

GENDER AND SCIENTIFIC HEROISM

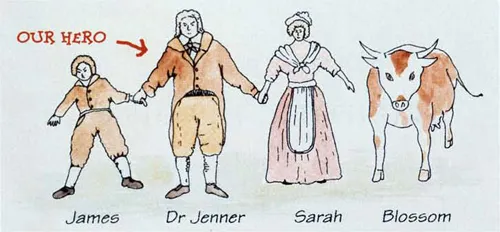

50 Jenner bookmark, 5 × 21 cm.

Published by the Jenner Appeal Trust, this bookmark is available at the Jenner Museum. Many galleries and museums use such items to promote themselves and their values.

‘OUR HERO’

Consider the bookmark produced by the Jenner Museum, located in Berkeley, Gloucestershire, where Edward Jenner lived and worked (illus. 50, 51). He is buried in the local church a few steps away, and the Museum is in his own house. The bookmark is a frieze of the significant players in the discovery of vaccination, including Blossom the cow. An oil painting of Blossom stands over the fireplace in the main room of the Museum, which owns at least three sets of her horns. Cows too can be heroes and generate relics. An arrow points to Jenner himself, with the explanatory words ‘our hero’. The image of Jenner on the bookmark is hardly a portrait in the strict sense, but it provides valuable insights into the kinds of heroism found among practitioners of science, medicine and technology.

Edward Jenner was born in 1749 into an educated and fairly well-off family. A number of family members were clergymen, which implies a certain level of intellectual sophistication. For our purposes, three aspects of his early life deserve attention. The first is his interest in natural history, which was sustained throughout his life. Natural history provided access to ideas and methods which were loosely scientific as well as a strong point of common interest between Jenner and John Hunter, his teacher and mentor, who became a figure of considerable importance in his pupil’s life. Second, Jenner’s training began with an apprenticeship to a local surgeon. Apprenticeship, as we have seen, is a very particular form of training; a long way from being abstract and bookish, it emphasizes practice, not medical theory. Surgery was based on manual skills, and although some surgeons were extremely well educated, it remained in this period an assembly of practical skills that depended on a good working knowledge of the body. Third, Jenner completed his medical education in London, where he attended private lectures and demonstrations, such as those given by the Scottish brothers John Hunter and his brother William, by George Fordyce, and by Thomas Denman and William Osborn. He also gained hospital experience and mixed with cosmopolitan men of science such as Sir Joseph Banks.1

51 Edward Jenner’s Study, now part of the Jenner Museum, Berkeley, Gloucestershire.

The Jenner Museum seeks to educate the public about Jenner and his achievements; it also presents material on immunology and the history of smallpox.

Jenner’s early life was thus quite varied, and it included being closely involved with people who were original and influential. He never became a metropolitan man, although he did extensive business in the capital and was a Fellow of the Royal Society. What models of achievement were then current, given that Jenner was a surgeon by training? It is hardly a secret that the reputation of surgeons was rather low in this period. In the popular mind, surgery was associated with butchering and butchery, and also with grave-robbing, since there was a dearth of bodies for anatomical purposes. It was also perceived as cruel and crude, its practitioners as coarse. It is important to recognize such stereotypes for what they were, but they nonetheless had a bearing on both the value accorded to certain occupations and the forms of public celebration that were possible. Over the eighteenth century, only a limited number of forms of heroism were available to medical practitioners. The example of Newton scarcely applied to them; alternatives were provided by doctors who achieved eminence by other means, such as writing, and those who were feted as important and influential practitioners with high-status clients, possibly royal connections and impressive incomes. In the first half of the eighteenth century, most of these were in fact physicians. The example of Richard Mead has already been mentioned; Mead was part of a special lineage of physicians with lucrative practices and royal connections of which there were only a few members.2

Surgeons were a rather different case, and I would suggest that the first key figure here was William Hunter rather than his younger brother John, whose influence was most marked at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries. William Hunter started out as a surgeon, and his importance derives from the remarkable economic, social and cultural success he enjoyed. Since he became a well-known figure in London, moving in court and aristocratic as well as in literary and artistic circles, William Hunter could be seen as a figure worth emulating. Like Mead, he was an enthusiastic and knowledgeable collector, as well as an expert anatomist. His dual interest in art and medicine was reinforced by his appointment as the first Professor of Anatomy on the foundation of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1768. Hunter was friendly with such men as Sir Joshua Reynolds, the Academy’s first President, who was to produce a memorable portrait of his brother John. It is perhaps significant that William was on easy terms with his upper-class clients, whereas John had a much less engaging manner.3 Yet it would, I think, be fair to say that William was not, in the sense that Edward Jenner became, a hero. Jenner came into contact with successful men of science in the metropolis, but while he was a student in London none of them offered a strong model of heroism (although it may be worth considering the extent to which figures such as Captain James Cook and Sir Joseph Banks, who had travelled extensively in the service of science, were worthy of emulation) (illus. 52). We may conclude that this was a period in which models of intellectual, and especially scientific and medical, achievement were both limited and labile. One clue as to how they changed may be found in the word our on the bookmark.

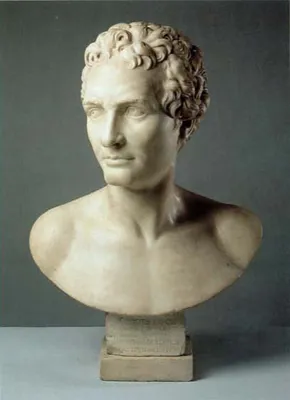

| 52 Lucien Le Vieux, Captain James Cook, 1790, marble bust, h: 58.4 cm. Cook is a special kind of hero in that while his achievements in navigation and exploration touched on many aspects of ‘science’, he could not easily be dubbed a ‘scientist’. He was awarded the Royal Society’s Copley Medal and worked closely with some distinguished naturalists. |

To whom does ‘our’ refer? The most limited way of reading it would be as a reference to those who produced the bookmark and those who would use it. But ‘our’ implies a collectivity of some kind, so what would join together makers and users of such a bookmark in a meaningful way? The only plausible interpretation, borne out by many other materials having to do with Jenner, is that he benefited humanity as a whole. We, the human race, since the late eighteenth century, have found in Jenner a hero who is ‘ours’ because his work is of universal value. Jenner’s contemporaries and followers certainly thought of it in that way, and they were quick to spread the message. Two hundred years later, Jenner’s achievement can be given another layer of significance. Smallpox is the only disease ever to have been eradicated through human action, although there are supplies stored in laboratories. Thus Jenner’s vaccination technique has a special status, not just by virtue of being unique but because it bears testimony to effective medical action (illus. 53).4

Another way of thinking about ‘our hero’ is in terms of national achievement. To return to Sir Isaac Newton, there is absolutely no doubt that by the time of his death in 1727 there was considerable national pride in a man whose intellect was so evidently gargantuan. Newton was important, and to be celebrated for his sheer brainpower, although we know that this public image had been carefully cultivated by his coterie. The precise form of his achievements was relevant to his status as a national hero: for instance, he was anti-Cartesian and Protestant.5 We might want to compare Newton with James Watt, who also became a major national hero. Watt was certainly admired because he was clever, but he was also an ingenious inventor and a successful entrepreneur who was seen to have given Britain considerable economic power. The unprecedented power that steam engines produced acted as a figure for Watt’s intellectual, and Britain’s economic, potency. It fired the imagination of his contemporaries, including Sir Walter Scott. One point about Watt that sets him apart from Newton but allies him with Jenner is the general human benefit that seemed to flow directly from his science. The first place where those benefits were felt was his own country.6

53 Plastic keyring containing a postage stamp designed by Peter Brookes, 1999.

This stamp was issued twice in 1999. Although it is not strictly accurate, in that Edward Jenner did not use Friesian cows, the image cleverly conveys an 18th-century ‘look’. Keyrings containing the stamp can be purchased at the Jenner Museum. For a contemporary silhouette of Jenner, see illus. 54.

Watt’s skills were in science and engineering, whereas Jenner’s were in medicine. These were and are very different domains. Although Watt was a brilliant innovator, he was building on established technological traditions. Prior to Jenner, medicine had had very few therapeutic successes of a significant order. Furthermore, smallpox was a special disease, especially lethal to the young and frequently leaving its victims dreadfully disfigured. To tame a disease of this kind was an achievement indeed. The point is even more significant when we consider the limited range of operations that surgeons undertook. They could cut things off and deal with wounds; internal surgery was extremely limited. In other words, surgery – Jenner’s occupation – was reactive rather than preventative.

Let us stay for a moment with the idea of preventative medicine. This was one of the main enthusiasms of eighteenth-century practitioners, including physicians, but what they mainly offered in this connection was advice about lifestyle. Innumerable medical advice books aimed at various markets were published during the eighteenth century. Little of this was new; indeed it drew on centuries of interest in hygiene. Although this branch of medicine had a noble lineage going back to Hippocrates, it was not thought of as particularly modern, and it certainly did not require much expertise, although there was a certain pretence that it did.7 In developing a new technique, vaccination, that made inoculation easier and safer, Jenner was doing something special. By the same token, inoculation and vaccination were controversial; they involved a particular kind of meddling, giving people a disease in mild form to prevent something far worse. In practice, neither was a particularly intricate procedure, and there were fierce disputes about who should and should not be allowed to practise them. Disputes arose precisely because there was a medical marketplace in which it was virtually impossible to control all those who set up practice, as many inoculators did, running special houses where clients could go and stay during their treatment.8

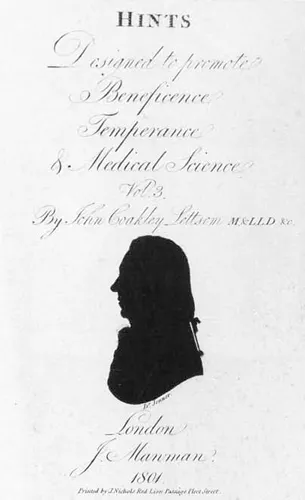

54 J. Miers, Title page with aquatint silhouette of Edward Jenner, from J. C. Lettsom, Hints Designed to Promote Beneficence, Temperance, and Medical Science (1801). Lettsom published a great deal and was often embroiled in controversy. Having thrown himself into the defence of Jenner’s ideas, he gave their association tangible form by using Jenner’s portrait on the title page of one of his own books. | |

55 James Northcote, Edward Jenner, 1802, oil on canvas, 109.2 × 86.4 cm.

Northcote’s first portrait of Jenner bears eloquent testimony to the importance of medical networks for both the public relations side of medicine and the commissioning of portraits. It was commissioned by medical admirers in Plymouth, who chose an artist born in their area.

Jenner presented the possibility of a new type of prevention, and he performed one further act that is central to the type of hero he became. He did not keep his discovery a secret or seek to make personal financial gain from it. In this sense, he was visibly altruistic. To fully understand the significance of his attitudes, we need to return to the spectre of quackery. Quacks were thought to be motivated by greed, and one of the most significant manifestations of their desire for wealth was the sale of remedies. If, as was invariably the case, the recipe for these was secret, then establishment practitioners were particularly infuriated. The combination of secrecy and financial gain flew in the face of a particular model of scientific and medical...