![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

• In 1997, Congress enacted cost-cutting reforms to Medicare that reflected expert consensus about the best ways to moderate growth trends in health care costs, such as limiting overly generous reimbursements to health maintenance organizations and home health providers. The legislation also established a “sustainable growth rate” formula for reimbursing doctors under Medicare, as well as a new program to support health services to the children of low-wage workers. This latter program—the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)—also reflected expert consensus on the long-term benefits of improving health outcomes for children. The legislation passed with broad bipartisan support in both houses of Congress.

• Beginning in 1999, and in virtually every subsequent year for the next decade, provisions of the 1997 Medicare reforms were trimmed back in the face of vigorous lobbying by health care–provider groups. Bipartisan majorities in Congress passed revisions in 1999 that were estimated to increase Medicare spending by $27 billion over ten years, followed by legislation in 2000 that was estimated to increase spending by $82 billion in the next decade. Although doctors failed to eliminate the sustainable growth-rate formula, aggressive lobbying by the American Medical Association and other physicians’ groups led Congress to pass “doc fix” legislation every year between 2003 and 2009, which temporarily suspended the limits and raised doctors’ fees under Medicare.

• In 2010, President Barack Obama signed legislation that extended health insurance coverage to millions of uninsured Americans. This law marked the culmination of decades of Democratic efforts to establish a program of universal health insurance. Hence, President Obama’s success at passing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was considered a major political victory, particularly in light of President Bill Clinton’s failure to pass a reform bill in 1994. It was also an exceedingly partisan accomplishment. Not a single Republican voted in favor of the act in either the House or the Senate. Moreover, both real and imagined provisions of the bill—such as the requirement that all individuals carry health insurance and populist concerns about supposed “death panels”—alarmed many citizens, rallied conservatives, and contributed to Republican victories in the 2010 midterm elections. These victories spawned efforts in the 112th Congress to repeal the law.

As these examples show, the federal policy process can vary widely from one enactment to the next, even within a single field such as health care. The process may be guided by the norms of technical experts in one case, dominated by narrow interest groups in another, led by the president and party leaders in a third, or driven by populist sentiment in a fourth. Some policies race through the process at breakneck speed, while others become stuck in a policy quagmire for years or decades. Some emerge fully grown almost overnight, while others evolve in slow, incremental stages. Some are shaped in the glare of public visibility while others are crafted in the shadows by obscure subcommittees and bureaucratic agencies.

Conventional treatments of the policy process have difficulty accommodating this complexity. Civics texts portray a single, idealized model of “how a bill becomes law,” journalistic treatments tend to emphasize the role of special-interest lobbying and campaign contributions to Congress, and many college textbooks describe a common set of stages through which all policies progress, from agenda setting to policy implementation. While these approaches have their merits, they fail to convey—much less explain—the great diversity in political processes that shape specific policies in contemporary Washington.

Rather than describing a single route along which all policies progress, this book argues that the policy process is best understood as a set of four distinctive pathways of public policymaking, each of which requires different political resources, appeals to different actors in the system, and elicits its own unique set of strategies and styles of coalition building:

• The traditional pluralist pathway, where policies are constructed largely by the processes of mutual adjustment among contending organized interests, through bargaining, compromise, and vote trading. Unorganized, poorly represented interests, which may include the public at large, typically exert less influence here. Policy outcomes that emerge from the pluralist pathway are prone to be modest and incremental in nature.

• The partisan pathway has long provided the traditional route for large-scale, nonincremental policy changes. In this model a strong party leader—typically a president—sweeps into office with large, unified party majorities in Congress. This leader mobilizes the resources of office to construct a coherent legislative program and rallies the public and the party followers behind it. Under such circumstances, the legislative backlog of a political generation may be disposed of in a few months. But such periods of unity tend to be brief, as party coalitions generally succumb to internal, centrifugal forces or to subsequent electoral losses.

• In more recent years especially, an expert pathway has developed, which provides a route for both incremental and nonincremental policy change. This pathway is dominated by a growing cadre of policy experts and professionals in the bureaucracy, academia, and Washington think tanks. Their influence derives from the persuasive power of ideas that have been refined, refereed, and perfected within specialized policy communities. Especially where policy experts have achieved a broad degree of consensus, they can serve as effective reference points for the mass media, decision makers, and other nonspecialists in the policymaking arena.

• Finally, a symbolic pathway has become increasingly prominent in recent years. Like the expert pathway, it too is built around the power of ideas. But symbolic ideas tend to be simple, value-laden beliefs and valence issues whose power lies in their appeal to commonsense notions of right and wrong rather than expert appeals to efficiency and empirically demonstrated effectiveness. The symbolic pathway relies heavily on policy entrepreneurs and communication through the mass media to bridge the gap between policymakers and the general public.

Overall, these four distinctive pathways are distinguished from one another along two critical dimensions, graphically portrayed in table 1.1. One dimension is the scale of political mobilization. Does the policy in question elicit attention from a narrow and specialized audience, or is it the focus of attention and concern by a large-scale mass audience? Ever since the publication of E. E. Schattschneider’s small but influential book The Semi-Sovereign People, political scientists have paid attention to the fact that the scale of political mobilization—what Schattschneider called the “scope of conflict”—could have an important and systematic impact on the politics of an issue. In Schattschneider’s words, “every change in the scope of conflict has a bias. … That is, it must be assumed that every change in the number of participants is about something that the newcomers have sympathies or antipathies that make it possible to involve them. By definition, the intervening bystanders are not neutral. Thus, in political conflict, every change in scope changes the equation.”1

The second important dimension, and one that more recent scholarship has directed attention to, involves the principal method of political mobilization. What is the predominant form of coalition building involved in enacting a given policy? Is support constructed primarily through organizational methods—principally through the efforts of specific interest groups or political parties—or is support gathered primarily through the construction and manipulation of ideas?

Table 1.1. The Four Pathways of Power

(with prototypical examples)

Traditional politics—and traditional political science models—emphasized organizational methods of coalition building. As far back as the Federalist Papers, American politics have been viewed as a battle between contending “factions” and interests. Over time, the understanding of factions took note of more complex forms: political organizations, social movements (such as the abolitionist and prohibition movements of the nineteenth century), and the established farm, business, and labor groups of the twentieth century. Enveloping, embracing, and competing with interest groups were political parties, which formed the backbone of American electoral politics from the early nineteenth century on. Parties by the late nineteenth century were described as mass, militant armies of (white male) citizens, which dominated political communication, mobilized the electorate, and organized the government. Thus by the mid-twentieth century, American politics were encapsulated by the twin organizations of “parties” and “pressure groups.”2 These organizations remain important political actors today, as evident by the tremendous growth of Washington interest groups and the renewed strength of national party organizations and party leadership in Congress.

However, many modern analyses of public policymaking have tended to emphasize the power of ideas over that of traditional organizations. Scholarly books analyzing the politics of deregulation, tax reform, and welfare reform all identified the politics of ideas, rather than parties or interests, as the critical dynamic leading to enactment.3 In one sense, of course, this is nothing new. Plato plumbed the intersection of ideas and politics in The Republic, while in the modern era the potential power of political ideas was captured in Victor Hugo’s nineteenth-century aphorism “Greater than the tread of mighty armies is an idea whose time has come.” But like many aphorisms, the concept was widely acknowledged and unevenly developed. Our examination of contemporary policymaking indicates that the politics of ideas are increasingly important and that they come in the two very distinctive flavors identified above: the expert and the symbolic.

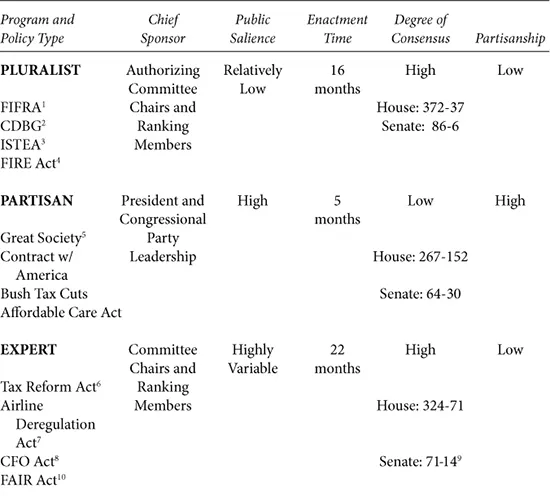

A Prima Facie Case for the Pathways of Power Framework

Although this simple model of four policymaking styles has intuitive appeal, does it really describe or help explain observable forms of federal policymaking? Ultimately, that is the question to which this entire book is devoted. But a crude, prima facie case for the pathways of power framework is suggested in table 1.2, which compares important features of sixteen different policies—or related groups of policies—drawn mainly from the last half century. Four policies, or sets of policies, were selected as exemplars of each policy pathway and compared along several different dimensions: sponsorship, enactment speed, public salience, degree of conflict, and level of partisanship. Because they were not drawn as a random or representative sample of all federal policies, these cases are intended to be only illustrative. They do not provide a definitive test of the pathways framework or all of the critical variables that distinguish pathways from one another. However, the very different patterns of political behavior elicited by these archetypes suggest the value of exploring the pathways-of-power model in greater depth and rigor in the remainder of this book.

For example, if one examines their legislative sponsorship in Congress, distinctive patterns emerge between the four policy types. The chief legislative sponsors of the four pluralist policies examined in table 1.2 were the chairmen and/or ranking minority members of the authorizing committees with jurisdiction in Congress. The same was true of the four examples of the expert pathway. In both cases the narrow scope of political mobilization coincided with a dominant role assumed by leaders of the relevant policy subsystem. In contrast, policy leadership in the partisan pathway was typically exerted by the president and/or congressional party leadership. Committee leaders are often deeply involved in crafting the legislative details in these instances, but the basic framework of the response, as well as its driving energy, ultimately come from those at a higher pay grade. Chief sponsorship of symbolic policies, in contrast, is highly variable in the four cases examined here, with leadership coming from individual policy entrepreneurs in the case of Megan’s Law (which required public notification of sex offenders’ residence in a community), from subsystem leaders in the National Environmental Policy Act, and from party leadership in the post-9/11 Afghanistan War resolution and emergency supplemental.

Table 1.2. Archetypes of Pathway Politics

Patterns of policy incubation and enactment also vary systematically among the four pathways, as represented by these archetypal policies. In the four examples of pluralist policymaking, the incubation period—or time between the first serious discussion of the issue and its enactment—averaged several years. In the session of Congress when each program was finally enacted, the period of congressional consideration averaged sixteen months from introduction to final decision. In contrast, the four archetypes of the partisan pathway had incubation periods that could extend beyond ten years.4 When these programs were finally enacted by Congress, however, they typically raced through in a matter of months, often on the wave of a landslide election victory that gave the victorious party claim to a popular “mandate.” The average enactment time for several major programs of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society agenda of 1965, the Republican Contract with America in 1995, and the Bush-era tax cuts of 2001 was five months, not far off the goal of a hundred days established by President Roosevelt in 1933. The true speed record was set, however, by the four examples of symbolic policymaking in table 1.2. These programs truly did race through Congress in about a hundred days from introduction to enactment. Most remarkably, their incubation period was practically identical to their enactment phase, indicating that these ideas jumped onto the fast track to adoption practically the first moment they were seriously proposed. This is in stark contrast to the slow and steady progress of persuasion that marks expert-driven legislation in the expert pathway.

Finally, when measured by the comparison of “ideal types,” the four pathways appear to elicit demonstrably different levels of salience, conflict, and partisanship in the legislative process. Pluralist policymaking is characterized by low levels of public salience, conflict, and partisanship. The four pluralist cases examined in table 1.2 were obscure to most members of the general public, and yet they passed by an average vote of 372-37 in the House and 86-6 in the Senate. In sharp contrast, the partisan pathway is typically marked by high levels of salience, conflict, and partisanship. Six specific pieces of partisan legislation—including two each from the Great Society and the Contract with America—passed on average votes of 267-152. All were subject to enormous media attention and passed on divisive, party-line votes, although with some defections from the minority party in Congress. Although the four cases of expert policymaking were largely consensual—with muted partisanship and frequent use of noncontroversial voice...