![]() I

I

Theoretical and Computational Linguistics![]()

1

Negation in Moroccan Arabic: Scope and Focus

NIZHA CHATAR-MOUMNI

Université Paris Descartes

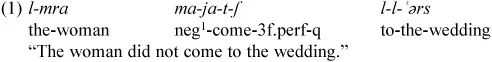

STANDARD SENTENTIAL NEGATION in Moroccan Arabic (MA) is marked with both elements ma- and -ʃ (or its variant -ʃi). According to the contexts, these elements can be split in a discontinuous form or merged in a continuous form. For example, in direct assertions, the discontinuous form surrounds a verbal predicate (1) or a quasi-verbal predicate, (2) whereas the continuous form precedes a nonverbal predicate (3):

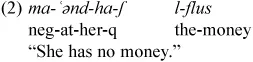

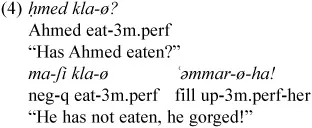

In marked utterances—for example, adversative utterances—the discontinuous form can be used with a nonverbal predicate (4) and the continuous one with a verbal predicate (5):

In MA, the first element (ma-) is required in all contexts, while the second element (-ʃ) can—or must—fall in various contexts.2 In this chapter I focus on issues entailing the presence or the absence of -ʃ in the context of a verbal (or a quasi-verbal) predicate. Relying on Muller (1984), I argue that MA sentential negation results from the association between the neg(ator) ma- and a q(uantifier).3 I claim that, in order to satisfy the “negative association,” ma- must be attached to an undefined quantifier. The presence or the absence of the element -ʃ in MA is related to the presence or the absence of the [+undefined] feature.

The chapter is organized as follows: The first section reviews briefly the “Negative Cycle” (Jespersen 1917) in French and Arabic; both languages show obvious similarities in the process of negation renewal. The second section reviews the major “negative associations” in MA, and focuses particularly on the relationship between adverbial phrases of duration and the element -ʃ. The last section deals with MA negation as a scope’ unit, that is, a unit that applies a structural control on a fragment of the sentence (Nølke 1994, 120).

The “Negative Cycle”

Negation is a major theme of research in the grammaticalization framework. Further, it seems that the term grammaticalization was used for the first time by Meillet (1912) to describe and explain, among others, the evolution of sentential negation from Latin to French. It is well known that negation evolves by cycles. Jespersen (1917) developed the process of syntactic change of negation in a grammaticalization pattern named later by Dahl (1979) “Jespersen’s Cycle” or “Negative Cycle” (Van der Auwera 2010).

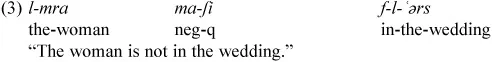

The renewal process of negation in Arabic and French is rather close. French sentential negation stems from the preverbal Latin negation non:

(6) Egeo, si non est (Cato)

“If I miss something, I pass.”

The Latin non—phonetically reduced and unstressed—evolved in Old French into ne and joined nouns meaning the smallest possible quantity in a given field of the experience, such as pas “step,” mie “crumb,” goutte “drop,” and point “stitch”:

(7) Quel part qu’il alt, ne poet mie chair (Chanson de Roland 2034).

“Wherever he goes, he cannot fall a crumb.”

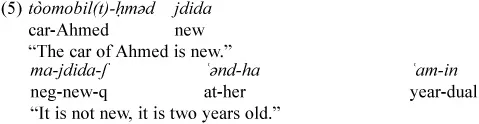

These nouns are selected according to the semantic class of the verb and according to the denoted event—pas “step” in the context of negated verbs of motion, goutte “drop” with negated verbs for “to drink,” and so on—emptied gradually of their lexical meaning, and fixed a grammatical one by contamination with ne. The possibilities reduced one by one in favor of point in formal register (8) and pas in informal register (9). Currently, in colloquial register, pas can be used alone, without the preverbal ne (10), in a third stage of the “Negative Cycle”:

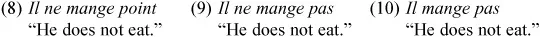

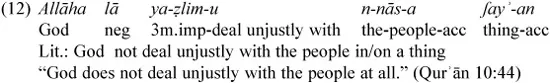

The MA negator ma- derives probably from Classical Arabic (CA), which marks sentential negation with a single unit: lā, lam, lan, mā or the negative copula laysa. As for the element -ʃ (or its variant -ʃi), it derives most likely from the CA ʃayʾan “a thing,” that is, the undefined noun ʃayʾ marked with the accusative as in (11) and (12) below. In these Qurʾānic examples, ʃayʾan, coupled with the negation lā, means respectively “anything” (nominal) and “at all” (adverbial):4

According to Lucas and Lash (2010), ʃayʾan “is found predominantly in the context of negation already in CA. In the Qur’an, for example, which consists of approximately 80,000 words, ʃayʾan occurs 77 times. Of these, fully 63 (81.8 percent) occur in the scope of negation.” The high frequency of ʃayʾan “a thing” in the scope of negation gradually made it sensitive to the negation and led it to become a negative polarity item (NPI).

Hence, negation has been reinforced through a minimizer in French—that is, an item denoting the smallest quantity in a field of the experience (pas “step,” goutte “drop,” etc.)—and through a term denoting a vague, an undefined quantity (ʃayʾan “a thing”) in Arabic. On contact with negation, this smallest or vague quantity is reduced to a zero quantity. Michèle Fruyt (2008, 2) rightly points out that: “L’histoire de ces termes résulte du raisonnement selon lequel, s’il y a absence d’une entité considérée comme infiniment petite dans un certain domaine d’expérience et même absence de la plus petite entité connue et concevable, il y a nécessairement absence de toute entité et donc il y a ce que l’on pourrait appeler, selon le modèle mathématique, ‘l’ensemble vide’ ou bien ‘l’absence absolue.’ L’emploi linguistique de la négation correspond ici à la dénotation d’une absence, puisque la négation porte sur une entité et non sur un procès.”5

Negation is closely related to quantification. That may be why, in the renewal process, Arabic and French negation have been reinforced through a unit denoting quantification. About French, Muller (1984, 94) emphasizes that “Il est bien connu que la négation implique une vision totale du domaine de quantification; pour dire: Il y a quelqu’un dans l’assistance qui est chauve, il n’est pas nécessaire de voir tout le monde. Cela est nécessaire pour pouvoir dire: Il n’y a personne dans l’assistance qui soit chauve. Ce pourrait être l’origine de la présence de quantifieurs en ancien français comme pas, mie, goutte, brin, point, sur lesquels porte la négation pour signifier que l’ensemble du domaine a été pris en considération.”6

Accordingly, for Muller, sentential negation results from the association between negation and a quantifier. In MA—as I argue in the two next sections—sentential negation results from the association between the neg(ator) ma- and an undefined q(uantifier).

Negative Associations in Moroccan Arabic

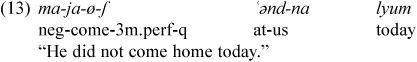

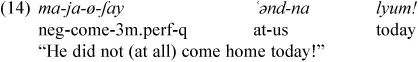

The standard “negative association” links ma- to the general and undetermined quantifier -ʃ (13), the reduced form of ʃay. In MA, the full form is still in use, most often to mark an emphatic negation (14). We can compare it with the French point, the stronger form of pas (cf. 8 and 9 above) used in formal register but also in order to mark an energetic negation.

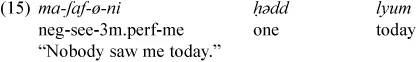

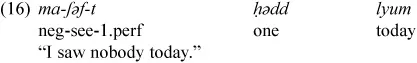

To cover the different domains of the experience, ma- attracted in its scope other quantifiers denoting all an undefined quantity and selected according to the semantic class of the verb and the denoted event. For example, for the feature [+human], ma- is associated to the undefined quantifier ḥədd, stemming from CA ʾaḥad “one,” the smallest numerical quantifier. Marçais (1935, 399) rightly pointed out that “Aucun mot n’est plus apte à exprimer la valeur indéfinie que le mot qui dénote l’unité: la notion un exemplaire pris entre plusieurs est en effet très proche parente de la notion un exemplaire non identifié”:7

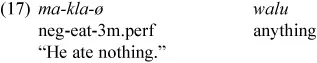

For the feature [-human], MA associates ma- and walu “anything” perhaps stemming from CA wa-law “and if,” “even if,” denoting the irrealis, the absence:

To cover the feature [+temporal], ma- is associated to ʿəmmər8–stemming from a word meaning “lifespan”–in order to mean “never.” We find a similar expression in Fren...