![]() PART I

PART I

Thinking about Cyber![]()

CHAPTER 1

An Introduction to National Security and Cyberspace

Derek S. Reveron

IN ITS SHORT HISTORY, individuals and companies have harnessed cyberspace to create new industries, a vibrant social space, and a new economic sphere that are intertwined with our everyday lives. At the same time, individuals, subnational groups, and governments are using cyberspace to advance interests through malicious activity. Terrorist groups recruit, train, and target through the Internet, organized criminal enterprises exploit financial data with profits that exceed drug trafficking, and intelligence services steal secrets.

Today individuals tend to pose the greatest danger in cyberspace, but nonstate actors, intelligence services, and militaries increasingly penetrate information technology networks for espionage and influence. This is likely to continue in the future as governments seek new ways and means to defend their interests in cyberspace and to develop their own offensive capabilities to compete in cyberspace. As an early example, the Obama administration released International Strategy for Cyberspace in May 2011, which defines four key characteristics of cyberspace: open to innovation, secure enough to earn people’s trust, globally interoperable, and reliable.1 Ensuring reliability against threats seems to dominate national security discussions today and raises concerns when thinking about future warfare.

Since the early 1990s analysts have forecast that cyberwar in the twenty-first century would be a salient feature of warfare. Yet, nearly twenty years later, individual hackers, intelligence services, and criminal groups pose the greatest danger in cyberspace, not militaries. But the concept of using cyber capabilities in war is slowly emerging. An example of this was the cyber attack that accompanied Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008. As Russian tanks and aircraft were entering Georgian territory, cyberwarriors attacked the Georgian Ministry of Defense. Though it had a minimal effect, the attack was a harbinger; future conflicts will have both a physical dimension and a virtual dimension. While not destructive, the attacks were disruptive. In the future, malicious code infiltrated through worms will disrupt communication systems, denial of service attacks will undermine governments’ strategic messages, and logic bombs could turn out the lights in national capitals. This approach was discussed during the 2011 NATO campaign in Libya, but was left largely in the conceptual phases.2

As a preview of what is to come, the 2010 Stuxnet worm was the first worm specifically designed to attack industrial control systems.3 Had the worm not been detected, hackers could have obtained control of power plants, communication systems, and factories by hijacking the infected systems. Theoretically, this outside actor could manipulate a control system in a power plant to produce a catastrophic failure. The source of the worm is purely speculative, but some experts saw this as the first true cyber attack against Iran’s nuclear infrastructure and credit it for slowing down Iran’s program.4

The 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review foreshadowed the dangers of Stuxnet and highlighted that, although it is a man-made domain, cyberspace is now as relevant a domain for Defense Department activities as the naturally occurring domains of land, sea, air, and space. The United States and many other countries, including China, Russia, Israel, and France, are preparing for conflict in the virtual dimension. In the United States, a joint cyber command was launched in 2010. With a modest two thousand personnel at its headquarters, the command derives support from fifty-four thousand sailors, eighteen thousand airmen, twenty-one thousand soldiers, and eight hundred marines who have been designated by their services to support the emerging cyber mission. The head of US Cyber Forces, Gen. Keith Alexander, sees future militaries using “cyberspace (by operating within or through it) to attack personnel, facilities, or equipment with the intent of degrading, neutralizing, or destroying enemy combat capability, while protecting our own.”5 The 2011 National Military Strategy directed joint forces to “secure the ‘.mil’ domain, requiring a resilient DoD cyberspace architecture that employs a combination of detection, deterrence, denial, and multi-layered defense.”6 The Defense Department strategic initiatives for operating in cyberspace include the following:

Treat cyberspace as an operational domain to organize, train, and equip so that the Defense Department can take full advantage of cyberspace’s potential.

Employ new defense operating concepts to protect Department of Defense networks and systems.

Partner with other US government departments and agencies and the private sector to enable a whole-of-government cybersecurity strategy.

Build robust relationships with US allies and international partners to strengthen collective cybersecurity.

Leverage the nation’s ingenuity through an exceptional cyberworkforce and rapid technological innovation.

7With this in mind, this book considers the current and future threats in cyberspace, discusses various approaches to advance and defend national interests in cyberspace, contrasts the US approach with European and Chinese views, and posits a way of using cyber capabilities in war. To be sure, the nature of and the role for cyberwar is still under debate.8 But this book establishes a coherent framework to understand how cyberspace fits within national security.

Cyberspace Defined

Writer William Gibson coined the term “cyberspace” in a short story published in 1982. Once confined to the cyberpunk literature and science fiction such as the movie The Matrix, cyberspace entered the real world in the 1990s with the advent of the World Wide Web. In 2003 the Bush administration defined cyberspace as “the nervous system of these [critical national] infrastructures—the control system of our country. Cyberspace comprises hundreds of thousands of interconnected computers, servers, routers, switches, and fiber optic cables that make our critical infrastructures work.”9 Today, the US Defense Department defines it as “a global domain within the information environment consisting of the interdependent network of information technology infrastructures, including the Internet, telecommunications network, computer systems, and embedded processors and controllers.”10

Like the physical environment, the cyber environment is all-encompassing. It includes physical hardware, such as networks and machines; information, such as data and media; the cognitive, such as the mental processes people use to comprehend their experiences; and the virtual, where people connect socially. When aggregated, what we think of as cyberspace serves as a fifth dimension where people can exist through alternate persona on blogs, social networking sites, and virtual reality games. Larry Johnson, chief executive officer of the New Media Consortium, predicts that over the next fifteen years we will experience the virtual world as an extension of the real one. Johnson believes that “virtual worlds are already bridging borders across the globe to bring people of many cultures and languages together in ways very nearly as rich as face-to-face interactions; they are already allowing the visualization of ideas and concepts in three dimensions that is leading to new insights and deeper learning; and they are already allowing people to work, learn, conduct business, shop, and interact in ways that promise to redefine how we think about these activities—and even what we regard as possible.”11

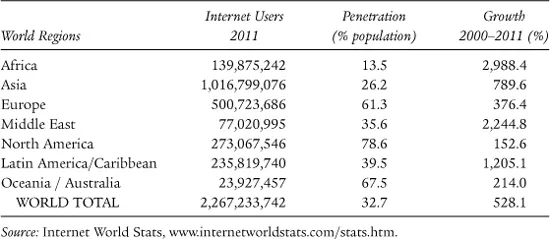

Gone are the stereotypes of young male gamers that dominate cyberspace; those that inhabit virtual worlds are increasingly middle-aged, employed, and female. For example, the median age in the virtual world “Second Life” is thirty-six years old, and 45 percent are women. Among Facebook users, about half are women.12 There are more Facebook users aged twenty-six to thirty-four than there are aged eighteen to twenty-five. The Internet has been the primary means of this interconnectivity, which is both physical and virtual. Due to the highly developed economies and its important role in the information technology sector, the highest Internet penetration rate is in North America. Yet, given its population size and rapid development, Asia has the most users (see table 1.1).

TABLE 1.1

World Internet Users

Cyberspace and National Security

The link between national security and the Internet has been developing since the Clinton administration in the 1990s. Yet there are significant differences between traditional domains such as airspace that make protecting cyberspace difficult. To begin with, no single entity owns the Internet; individuals, companies, and governments own it and use it. It is also arguable that there is not just one Internet but many. Governments also do not have a monopoly on operating in cyberspace. In contrast to heavily regulated airspace, anyone with a good computer or phone and an Internet connection can operate there. And, making it more challenging for governments, most of the cyber expertise resides in information technology companies. Yet, all are affected equally by disruptions in cyberspace; a computer virus disruption that occurs through a commercial website can slow down the Internet for government and military users as well as for private citizens.

As it relates to war, the Internet is both a means and a target for militaries. Former US deputy defense secretary William J. Lynn underscored how important the information infrastructure is to national defense. “Just like our national dependence [on the Internet], there is simply no exaggerating our military dependence on our information networks: the command and control of our forces, the intelligence and logistics on which they depend, the weapons technologies we develop and field—they all depend on our computer systems and networks. Indeed, our 21st century military simply cannot function without them.”13 Additionally, governments use the Internet to shape their messages through media outlets hosted throughout the Web. US military commanders use public blogs and operational units post videos to YouTube. This gives both the military and citizens unprecedented insight from pilots after they bomb a target, or from marines as they conduct humanitarian assistance. The transparency is intended to reduce suspicion, counter deceptive claims made by adversaries, and improve the image of the military. Yet there are limits to these potential advantages; the Pentagon is concerned that its personnel can also share too much data through Facebook or project a poor image that runs counter to its efforts through YouTube videos. Or, in illegal cases, military personnel can steal classified data and post hundreds of thousands of classified documents to sites like Wikileaks, which can undermine national security.

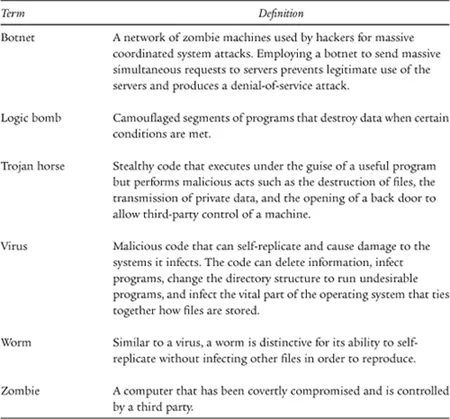

In contrast to traditional warfighting domains such as land, air, or sea, governments are not the only powers in cyberspace. Rather, individuals can readily harness technology to compete on a global scale. And it is worth noting that virtualization will continue this trend of democratizing the Internet, giving individuals tremendous power that was unthinkable even ten years ago. Satellite imagery used to be highly classified and limited by the US intelligence community, but now anyone can access imagery from an iPhone using Google Earth. Likewise, the complexity and cost of building a nuclear weapon limits their production to governments, but the same cannot be said for the virtual weapon of mass destruction that can destroy data and networks, undermine international credibility, and disrupt commerce. Malicious activity through worms, viruses, and zombies regularly disrupts Internet activity (see table 1.2). And there are already many examples of virtual activities impacting the physical world such as terrorists being recruited, radicalized, and trained on the Internet; communications being severed; or power production being disrupted. Illegal groups use cyberspace to move money, conceal identities, and plan operations, which makes it extremely difficult for the governments to compete. Consequently, governments are increasingly concerned with the cyber domain as a new feature within the national security landscape.

In some sense, there has always been an implicit national security purpose for the Internet. After all, the Internet was originally conceived of and funded by one of the Defense Department’s research organizations, then known as Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). Given the state of telecommunications and stand-alone computer systems that existed in the 1960s, researchers wanted to create a reliable network where a user’s system or location was unimportant to his or her ability to participate on the network. Charles Herzfeld, ARPA director from 1965 to 1967, explains the genesis of the network:

The ARPANET was not started to create a Command and Control System that would survive a nuclear attack, as many now claim. To build such a system was clearly a major military need, but it was not ARPA’s mission to do this; in fact, we would have been severely criticized had we tried. Rather, the ARPANET came out of our frustration that there were only a limited number of large, powerful research computers in the country, and that many research investigators who should have access to them were geographically separated from them.”14

This vision of a network became a reality in 1969 when a computer link was established between the University of California–Los Angeles and Stanford University. At the time, the connection was called “internetworking,” which later was shortened to the Internet. For thirty years, the Internet was largely the domain of universities, colleges, and research institutes. But when Tim Berners-Lee and his colleagues created the World Wide Web in 1990, commercial and social applications exploded. Within a few short years, companies such as Amazon (1995), Ebay (1995), Wikipedia (2001), Facebook (2004), and Khan Academy (2009) founded a new industry and changed the way we live and work. Ongoing trends in web development tools suggest that the gap between the virtual and physical worlds is indeed narrowing.

TABLE 1.2

Cyber Threats Defined

Academic and commercial companies were pioneers in harnessing the Internet, and the government was a relative latecomer. Cyberspace first emerged as a distinct national security policy area in 1998 when President Clinton signed Presidential Decision Directive 63, w...