![]() Part I

Part I

The Basics![]()

Chapter 1

Defining Contracting and

Contract Management

ORGANIZATIONS THROUGHOUT the world, in the public sector as well as the private sector, are becoming less hierarchical and increasingly part of interorganizational networks. Today’s effective public manager must learn to manage people outside of his or her home organization, as well as those within that organization. Some of the relationships between organizations are informal partnerships and interactions, but many are formal and contractual. Developing and maintaining both sets of relationships are important and growing elements of the work of the contemporary public manager. This book will focus on managing the formal relationship between organizations: the contractual relationship.1 This chapter will address five questions:

• What is a contract?

• How is it used in the public sector? What influences the make-or-buy decision in government?

• How often is contracting used in the United States?

• How do you manage a contract?

• Why focus on accountability and corruption?

What Is a Contract?

The definition of a contract is straightforward: “An agreement between two or more parties, especially one that is written and enforceable by law” (www.merriam-webster.com). Still, as Phillip Cooper has observed: “A contract is a legal instrument. Even so, great latitude is left to the contracting parties to an agreement to have the tools to fashion and implement it. Negotiations resulting in a meeting of minds are the dominant dynamic in most contracting” (2003, 13). While contracts involve negotiations between a buyer and a seller, a great deal of the attention in this volume will be devoted to the issues faced by the buyer, the government contract manager.

It is critical that the contract agreement be specific enough to provide a high quality good or service, but flexible enough to allow for that good or service to be modified to meet the government’s evolving needs. A contract specifies the good or service being procured, and typically includes information about

• Price

• Schedule

• The definition of the service or product being delivered

• The amount of service or good being provided

A defining characteristic of a contracted relationship in government is that the contractor is a separate and typically nongovernmental organization. For purposes of this work, a memorandum of understanding or cooperative agreement with another governmental organization will not be viewed as the type of contractual relationship we are analyzing.

The literature of public administration uses the term contracting to describe a number of relationships, and therefore it is important to be clear about the type of relationship we are analyzing. In their excellent analysis of contracting patterns among state governments, Jeffrey L. Brudney and his colleagues (2005, 394) note that

Despite the apparent heterogeneity of the privatization concept and the various methods for achieving privatization, in the U.S. context especially, this term is usually taken to mean government “contracting out” or “outsourcing” with a for-profit firm, a nonprofit organization, or another government to produce or deliver a service. Although the job of delivering services is contracted out, the services remain public, funded mainly by taxation, and decisions regarding their quantity, quality, distribution, and other characteristics are left to public decision makers (Brudney et al. 2005; compare Boyne 1998a, 475; Ferris 1986, 289).

What is key in Brudney’s definition, from our perspective, are the notions of public control, funding, and decision making. The government is the principal and the contractor is simply the agent. The issue of accountability will be a recurring theme of this work, and our definition of contracting leaves no ambiguity about the power relationship we see in government contracting. We understand that those who implement policy hold the power to define policy through administration, but that any exercise of this power by the contractor does not eliminate or diminish in any way government’s responsibility for the actions of contractors.

How Is It Used in the Public Sector? What Influences the Make-or-Buy Decision in Government?

Government agencies have always purchased goods and services and have developed relationships with vendors as part of the routine administration of public programs. When discussing the “competition prescription,” Don Kettl makes this point when he tells the story of George Washington’s complaints about the shoddy uniforms supplied to his revolutionary troops by private contractors. While these relationships with vendors continue, some analysts believe that contracting is different today than in Washington’s time. Stephen Goldsmith and William D. Eggers discuss the evolution from simple contracting for goods and services to contracting as a means of establishing and maintaining complex interorganizational networks. “In service contract networks, governments use contractual arrangements as organizational tools. Contractor and subcontractor service agreements and relationships create an array of vertical and horizontal connections as opposed to simple one-to-one relationships. Such networks are prevalent in many areas of the public sector, including health, mental health, welfare, child welfare, transportation and defense” (2004, 69).

In this view, contracting is a part of the organization’s fabric, and what Phillip Selznick (1957, 42) termed the “distinctive competence” of the network is indistinguishable from that of the organization. In fact, one key dimension of the value added by the organization is its ability to manage the network it has established.

The make-or-buy decision is made by organizations as they attempt to identify their own unique identity or distinctive competence. An organization may decide that to adequately perform its core function, it must shed other functions. Those other functions still must be performed for the organization to deliver outputs, but now they will be contracted out to other organizations.

Other management considerations that influence the decision to contract might include either the hope for a reduced price or the need for access to new or proprietary technology. Contracting can also in some instances provide higher quality services without a cost increase. The need for presence or capacity in a particular geographic location might also lead an organization to seek a partner or a contractor. Finally, the need to develop capacity quickly can lead a government organization to contract.

In some instances, the purpose of contracting is not to buy a particular good or service, but to develop capacity. Defense and high-tech contracting sometimes involves funding private research and the development of new technologies. Rather than investing in in-house scientific expertise, government decides to partner with a private firm for that purpose. A problem with this type of contracting is that often there are very few firms with the ability to compete for these “high end” contracts. This can lead to sole-source procurements, higher prices, and the appearance of impropriety. In addition, as Patrick Dunleavy has observed, “taking on a contractor may also create dependency on them, as when agencies build up data on one proprietary computer system and then find that major transition costs attach to shifting to an alternative supplier. In … these circumstances, effective market competition at the recontracting stage is prevented, and firms taking over government functions have every prospect of making super-normal profits with a particularly heavy cost in social welfare terms” (1991, 246).

Dunleavy also believes that the management preferences and self-interest of government contract managers can provide incentives for noncompetitive contracting. According to Dunleavy,

Policy-level staff are keenest to shift over to contracting where they can deal regularly with a few large corporations which have congruent management structures, are simple to monitor and have higher status and prestige. Large firms can better organize flowbacks of benefits for their official contacts, and they share bureaucrats’ well attested preferences for negotiated or selective tendering procedures rather than open competition (Turpin, 1972). But senior bureaucrats have less to gain from privatizing activities in highly competitive markets. Small businesses are constantly shifting, hard to monitor, prone to failure and their performance is highly sensitive to personnel changes. Bureaucrats’ preferences thus distort privatization policy, promoting contracting-out where agencies become dependent upon a few oligopolistic suppliers, but resisting it where competitive markets exist (1991, 241).

While we do not find evidence of contractors actually resisting competitive markets where they exist, it is true that the ideological preference for privatization can lead to contracting in noncompetitive markets. Moreover, while there are sound managerial reasons to contract, not all decisions to contract are based on management criteria. Sometimes the decision to contract is based on a political calculus. This might include an ideological preference for the private sector and antigovernment sentiment. It might be based on a desire to manage public relations and make it appear as if the government is not growing. Paul C. Light has written extensively on the “true size of government,” and in reviewing the growth of federal contracting he notes that

the government’s hidden workforce has crept to its highest level since the end of the Cold War. According to new estimates by the Brookings Institutions Center for Public Service, which I direct, federal contracts and grants generated just over 8 million jobs in 2002, up by more than 1 million since 1990. When these off-budget jobs are added to the civil service and military head count, the true size of the workforce stood at 12.1 million in October 2002, up from 11 million in October 1999. The true size of government is still smaller than it was before 1990. The end of the Cold War resulted in cutbacks of more than 2 million onand off-budget jobs at the Defense and Energy departments and NASA by 1999. But according to the center’s triennial inventory, based in part on estimates generated by Eagle Eye Publishers, the federal government has added back more than half of that head-count savings. But even as cuts were under way at Defense, Energy and other agencies added roughly 300,000 jobs back into government between 1993 and 1999. In the three years since, civilian agencies have added 550,000 more jobs and Defense has added roughly 500,000 (2003, 80).

While population grows and services must be expanded to meet growing needs, antigovernment ideologues more interested in “starving the beast” than delivering well-managed services force contracting on reluctant public managers. For example: “The 1970s witnessed an antibureaucratic mood that sought to limit the bureaucracy’s power through various budgetary approaches, reorganizations, reforms, and spending limitations such as California’s Proposition 13. Though not without efficacy and utility, overall such approaches are inadequate to the task. They must be augmented by an effort to maximize the political representativeness of public bureaucracy” (Krislov and Rosenbloom 1981, vii). Nevertheless, this type of contracting is a fact of life in the United States, and it distorts the analysis of make-or-buy choices in many public organizations.

How Often Is Contracting Used in the United States?

While contracting is increasing all over the world, this work will focus on the United States. As Barbara Romzek and Jocelyn Johnston have observed, “[g]overnments at all levels have expanded the range of services they deliver through contracts—from traditional ‘make-or-buy’ decisions for defense weaponry, highway construction and fleet purchases, to contracting for the ongoing provision of specialized social services” (2005, 436).

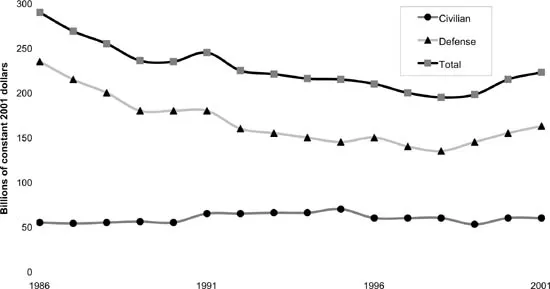

At the federal level, contracting increased in the late 1990s after declining at the end of the cold war in the late 1980s. As figure 1.1 indicates, defense contracting strongly influences the overall trends in federal contracting. The general tendency toward increased outsourcing is difficult to find in the data due to the size of the defense budget and its volatile nature over the past two decades.

Federal agencies procured more than $235 billion in goods and services during FY2001, reflecting an 11 percent increase over the amount spent five years earlier (U.S. GAO 2003). Despite the rapid increases in contractual spending, it must be noted that in FY2001, the $235 billion spent at the federal level represented about 10 percent of the entire budget. While there are examples of mismanagement in contracting, such as those in Iraq and New Orleans, fears of what H. Brinton Milward and Keith G. Provan (2000, 359) have termed a “hollow state” (without the capacity to manage contracts) are probably premature at the federal level: “Overall, contracting for goods and services accounted for about 24 percent of the government’s discretionary resources in fiscal year 2001. However, contract spending consumed between 34 percent and 73 percent of the discretionary resources available to the four largest acquisition spending federal agencies” (U.S. GAO 2003). The analysis by the U.S. Government Accounting Office, now called the Government Accountability Office (GAO), indicates that certain types of spending are more likely to be in the form of contracting than other types of spending. For example, spending for communications equipment and computer equipment and support also tends to be in form of contracts with private parties. According to GAO,

Figure 1.1 Trends in Defense and Civilian Agency Contracting Dollars, 1986–2001

Source: www.afge.org/Documents/CapReport.pdf.

Further growth in contract spending, at least in the short term, is likely given the President’s request for additional funds for defense and homeland security, agencies’ plans to update their information technology systems, and other factors. For example, the President’s fiscal year 2004 budget request reflects steady increases in DOD’s discretionary budget authority, as well as increases in the budgets of other agencies involved in homeland security. Additionally, the President’s budget request reflects increased investment in information technology both for new systems and for related support (U.S. GAO 2003).

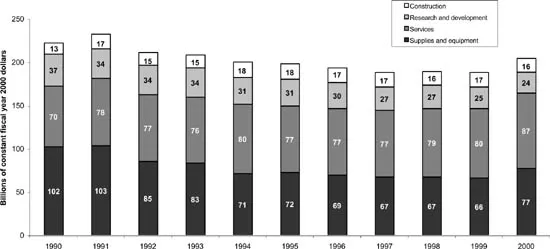

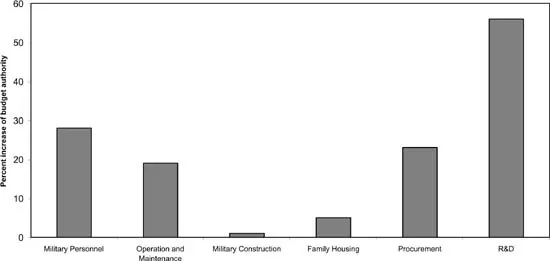

At the federal level we see some types of contract spending increasing, while other types of spending are either flat or declining. Supplies and equipment purchasing drops while service contracting grows. Of course, some of the supplies and equipment no longer need to be purchased by government contract if contractors are purchasing it for their own use in delivering services. Figure 1.2 shows changes in federal contracting by categories of spending. According to GAO, “the growth in services has largely been driven by the government’s increased purchases of two types of services:

• information technology services, which increased from $3.7 billion in fiscal year 1990 to about $13.4 billion in fiscal year 2000; and

• professional, administrative, and management support services, which rose from $12.3 billion in fiscal year 1990 to $21.1 billion in fiscal year 2000” (U.S. GAO 2001).

Figure 1.2 Changes in Federal Contract Spending by Categories, Fiscal Years 1990–2000

Source: GAO analysis of data extracted from the Federal Procurement Data System for actions exceeding $25,000; www.gao.gov/new.items/dØ1753t.pdf.

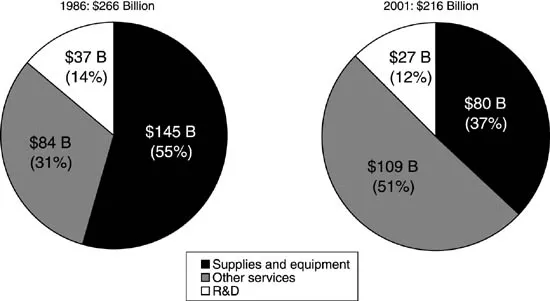

Figure 1.3 Contracting Activity Has Shifted

Source: www.afge.org/Documents/CapReport.pdf.

In the past several years, the growth of contracting at the federal level has followed a pattern of spending growth by the Department of Defense (DOD). The war in Iraq and the war on terrorism that began in late 2001 have resulted in increased spending. According to the White House web site in late 2005, Defense Department procurement grew more than 20 percent from 2001 to 2004. In discussing DOD’s increased spending the White House site observed that

the Department of Defense (DOD) is currently on the front lines of the War on Terror. As of December 14, 2003, there were 12,387 U.S. military troops deployed to support Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and 125,141 to support Operation Iraqi Freedom. These troops are fulfilling the President’s commitment to take the war on terror to the terrorists…. Since taking office, President Bush has consistently built defense strength. In fact, in constant 2004 dollars, defense spending has only been higher twice since World War II—during the Korean War and at the peak of the Cold War buildup. While some of this spending may be attributed to the War on Terror, President Bush committed to and has succeeded in steadily growing the base budget of DOD from $296.8 billion when he took office to $401.7 billion in the 2005 Budget. This 35–percent increase to the Department’s base budget helps fulfill the President’s commitments and ensures a fighting force that is second to none.2

While the picture at the federal level is far from uniform, state and local contracting provides a clearer picture. At the state and local level, data indicate that contracting is increasing. One way to assess this trend is to examine spending trends within cities (fig. 1.3). In many respects, government’s funding “funnel” tends to end at the local level, where services are actually delivered. Management trends tend to be more directly related to performance, since performance is more easily observed. If the garbage doesn’t get picked up, one doesn’t need a major study to learn about the failure—a keen sense of smell will do. The make-or-buy decision may be influenced by ideology, but in the end, reality seems to play an important role.

Nevertheless, since privatization and contracting of services normally entails “significant changes in the form of service provision, either reduced quality standards, or decreased public or consumer control over service provision” (Dunleavy 1991, 241), accountability of the bureaucracy is key. The separation between the “policy level bureaucrat” and the citizen he or she is serving can make it difficult to implement proper contracting of the services. What a policymaker may view as an improvement may in reality be something different. With most funding ending at the local level, it is important to ensure that implementation of contracting at the local level is just as sound as that at the federal level. Often “policy level bureaucrats’ welfare is little affected, especially where there is a wide social gap between senior officials and their agencies’ clients in terms of class, gender, age or ethnicity—as in most welfare state agencies dealing with the poor, elderly, unemployed, disabled, or homeless. Even in policy fields where bureaucrats themselves consume public services, spatial segregation can recreate a wide social gap between senior officials and clients—as when the schooling, health care or environmental services in run down areas are managed by officials living in more congenial parts of the metropolis” (Dunleavy 1991, 241).

Figure 1.4 Defense Department Spending Trends, 2001–4

In New York City, government contracting has grown dramatically over the past several years. According to the NYC Mayor’s Office of Contract Services’ annual report on “Agency Procurement Indicators” (2005), contracting increased from $7.3 billion in FY2002 to $9.1 billion in FY2003, and from $9.5 billion in FY2004 to $11.4 billion in FY2005. These data are in absolute and not constant dollars, but with a total budget ranging from $42.7 billion in FY2002 to $46.3 billion in FY2005, contracting has grown from about 17 percent of total city spending to 25 percent. One could argue that most of this increase is in contracts related to increased capital spending, but in fact capital spending during this period was a relatively fixed $6 billion per year. In some areas such as social services delivery, the city has gradually gotten out of the business of providing direct services and now manages an extensive network of nonprofit service providers. This is particularly pronounced in areas such as homeless and foster care services in New York. While most government...