![]() PART I

PART I

THE INSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL CONTEXT![]()

Chapter 1

An Introduction to Mission Creep

Gordon Adams and Shoon Murray

Overall, even outside Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States military has become more involved in a range of activities that in the past were perceived to be the exclusive province of civilian agencies and organizations. This has led to concern among many organizations … about what’s seen as a creeping “militarization” of some aspects of America’s foreign policy. This is not an entirely unreasonable sentiment.

—Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, July 15, 2008,

speech to the US Global Leadership Campaign, Washington, DC

Introduction

Over the past seven decades and, at an accelerating pace since the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 (hereafter 9/11), the Department of Defense has expanded its activities and programs into areas that go beyond core military operations. The Pentagon’s “mission creep” has been the result of a gradual accretion of responsibilities, authorities, and funding. It has been accommodated, and sometimes accelerated, by the choices made by senior policy officials and congressional representatives, and by the weaknesses and culture of the civilian foreign policy institutions themselves. The trajectory is toward a growing imbalance of resources and authority over national security and foreign policy between the Defense Department and the civilian tools of American statecraft.

In 2008, seven years into America’s global war on terrorism, the swift migration of traditionally civilian tasks to the Pentagon provoked even the secretary of defense and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS)—in a surprising role-reversal given normal turf conflicts in Washington—to warn about “creeping militarization” (Gates 2008). Secretary Robert Gates observed that “America’s civilian institutions of diplomacy and development have been chronically undermanned and underfunded for far too long—relative to what we traditionally spend on the military” (Gates 2008). Admiral Mike Mullen echoed the same concern. The JCS chairman alluded to a troubling political dynamic: Because the military is seen by the political leadership as more capable, it is increasingly used in noncombat missions, and given more resources, thereby leading to an even greater weakness in civilian agencies over time. Then the military is again asked to do more, and the dynamic continues. “I believe we should be more willing to break this cycle, and say when armed forces may not always be the best choice to take the lead,” Mullen concluded (quoted in Shanker 2009).

President Barack Obama, responding to such concerns, has sought to integrate the foreign policy/national security toolkit. His administration has emphasized the importance of approaching global issues from the perspective of the “3Ds: Diplomacy, Development and Defense” and using the “whole-of-government” to deal with them. Despite this rhetoric, however, the administration has not righted the balance. These efforts have been weakly funded, leaving a growing institutional and budgetary imbalance in place. Indeed, it is telling that retired three- and four-star generals and admirals continue to lobby Congress about the need to give resources to the State Department and the US Agency for International Development (USAID).1

The military’s mission creep is not new and it is not a secret. It has been the subject of news articles, conferences (including one that formed the basis for this book), think-tank reports, government studies, petitions to Congress, and congressional hearings. Still, there has been no empirical study examining this trend across different issue areas of policy and over time. This book fills that gap.

Warning Signs of Mission Creep after 9/11

Why were Gates and Mullen, and so many others, concerned about the weakening of the civilian tools of government? What signs did people see that the military services and the Pentagon were increasingly expanding into civilian space after 9/11? What had changed?

Most striking, the military expanded its development, governance, and humanitarian assistance programs around the world—activities such as drilling wells, building roads, constructing schools and clinics, advising national and local governments, and supplying mobile services of optometrists, dentists, doctors, and veterinarians overseas.2 The examples are plentiful: Army National Guardsmen drilling wells in Djibouti; the US Army Corps of Engineers building school houses in Azerbaijan; and US Navy Seabees building a post-natal care facility in Cambodia, to cite a few (Redente 2008; Ward 2008; Burk 2012). Many development practitioners became suspicious of such increased military activity in their area of expertise and a public debate ensued in Washington about DoD’s proper role in overseas developmental assistance. Joe Biden, then chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, described the trend that had raised concerns in a 2008 hearing on the topic: “Between 2002 and 2005, the share of U.S. official development assistance channeled through the Pentagon budget surged from 5.6 percent in 2002 to 21.7 percent in 2005, rising to $5.5 billion. Much of this increase has gone towards activities in Iraq and Afghanistan. But it still points to an expanding military role in what were traditionally civilian programs” (US Senate 2008).

The Pentagon even incorporated nation-building activities into its military doctrine. For example, the 2005 DoD Directive 3000.05 made “stability operations” a “core U.S. military mission,” defining these as “various military missions, tasks, and activities … to maintain or reestablish a safe and secure environment, provide essential governmental services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction, and humanitarian relief” (US Department of Defense 2005a). It is a remarkable development that the Pentagon would give marching orders for the services and commands to consider noncombat tasks on par with warfighting. The individual services then reflected the changed priorities in their own guidance documents.3

For many, the US Africa Command (AFRICOM), stood up in 2008, came to symbolize this broader perspective on military responsibilities. It was expected that the command would do little fighting but much training and development, that it would focus more on prevention than on warfighting, and that it would even incorporate civilians from the State Department into the leadership of the command. Tasks such as “reconstruction efforts,” “turning the tide on HIV/AIDS and malaria,” and “fostering respect for the rule of law, civilian control of the military, and budget transparency” were included in AFRICOM’s theater strategy (Reveron 2010, 87). The Combined Joint Task Force for the Horn of Africa (CJTF-HOA) based at Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti, the military’s primary forward presence in Africa, focused most of its activities on civil affairs projects such as humanitarian assistance, medical care, and building infrastructure.4

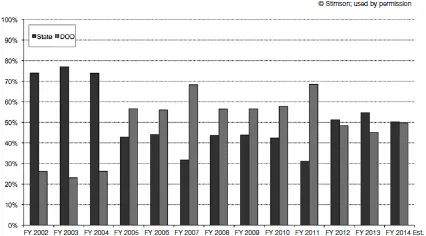

Because of its expanded focus on stabilization and reconstruction operations, DoD requested and was provided new authorities, programs, and funding. Programs such as the Global Train and Equip (known as “Section 1206”) or the Commander’s Emergency Response Program (CERP) allowed the generals and admirals who oversee US military activities abroad (known as the geographic combatant commanders) greater flexibility to distribute security and developmental assistance. As a consequence, the State Department, which at one time had sole authority over foreign military aid and training programs, lost ground. As shown in Figure 1.1, the share of overall US security assistance administered through the DoD rose from about 25 percent to almost 70 percent in the post–9/11 era, although it started to come down in 2012. (See Serafino, Chapter 7, for an alternative analysis that excludes war-related programs.)

Media reports also warned of the military’s increasing involvement in public information campaigns abroad. Headlines in the New York Times, Washington Post, and USA Today read: “Hearts and Minds: Pentagon Readies for Efforts to Sway Sentiment Abroad,” “The Military’s Information Is Vast and Often Secretive,” and “Pentagon Launches Foreign News Websites.”5 Most stories were about information campaigns and “psychological operations” that the military ran during the Iraq War. But a more lasting institutional change also occurred. The Special Operation Command (SOCOM) has taken on a public diplomacy role, working with the geographic combatant commanders; it has created military-run web sites and other informational material to reach foreign audiences and has sent out small teams to embassies around the world to do “information operations” (Rumbaugh and Leatherman 2012; Carlson, Chapter 8).

Even the civilian agency closest to the Pentagon as a “hard power” tool—the Central Intelligence Agency—has seen DoD expanding directly into its turf since 9/11, both in intelligence gathering and analysis and in covert operations. The Pentagon’s Special Operations Command (SOCOM)—not the CIA—was given the lead role to synchronize the “global war on terror.” Early on, SOCOM sent out teams to conduct its own intelligence, sometimes without the knowledge of the ambassador (Murray and Quainton, Chapter 9). The Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), a component of SOCOM, has been deeply involved in the “shadow war” to hunt down and capture or kill al-Qaeda operatives in Afghanistan and elsewhere (Mazzetti 2013a; Kibbe, Chapter 11).

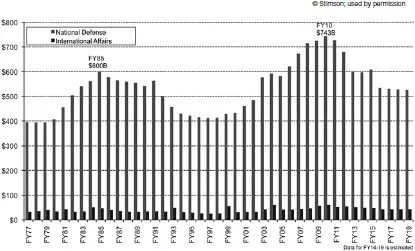

Basic appropriation levels point out the striking disparity in resources and personnel between the military and civilian institutions of statecraft. At more than $600 billion a year, the defense budget is twelve times the size of the total budgets available to the civilian foreign policy institutions (see Figure 1.2). The Defense Department workforce is more than a hundred times larger than the State Department and USAID combined (see Adams, Chapter 2). If the Reserves and National Guard are included, the personnel ratio is more than 155 to 1. Such a profound asymmetry between the military and nonmilitary agencies, as David Kilcullen observed, is not normal for other Western democracies. The “typical size ratio between armed forces and diplomatic/aid agencies for other Western democracies,” he wrote in 2009, “is on the order of 8–10:1” (Kilcullen 2009, 50). To bring home the US disparity in resources, Kilcullen used the now-famous fact that there are “substantially more people employed as musicians in Defense bands than in the entire foreign service” (Kilcullen 2007).

Figure 1.1

State and Defense Department Shares of Security Assistance FY, 2002–14

Sources: Defense and State Congressional Budget Justification materials; OMB Public Database; National Defense Authorization Acts.

Putting Post–9/11 Mission Creep into Historical and Political Context

The historical origins of this institutional imbalance are rooted in decisions made at the beginning of the Cold War. The National Security Act of 1947, the Truman Doctrine (1947), the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) alliance (1949), White House policy memorandum NSC-68 (1950), and the Korean War (1950–53) all played major roles in the creation of foreign policy and national security institutions that had not previously existed: a large, permanent standing Army, a unified civilian establishment to oversee all the military services, a standing intelligence service, and a national security coordination process in the White House—the National Security Council (Gaddis 1972; LaFeber 1973; Ambrose and Brinkley 2010).

Figure 1.2

National Defense and International Affairs Discretionary Budget Authority

Constant 2013 dollars (billions)

Source: OMB Historical Tables 5-6, 5-1, and 10-1.

Over the succeeding decades, defense budgets and capabilities rapidly surpassed those of the civilian agencies and the Defense Department grew more sophisticated in its strategic, program, and resource planning (Whittaker, Smith, and McKune 2011). From the war in Korea, which left a larger Army in place than before 1950, to Vietnam, to the 1990s, defense resources reached a high level of stability averaging roughly $400 billion in constant 2013 dollars. During the Cold War, the logic of the confrontation with the Soviet Union became a military logic6; the comparisons between the two superpowers were military comparisons. Defense budgets and capabilities grew as a direct consequence. Even after the end of the Cold War, US defense budgets remained high, and with the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq, the annual average defense budget between FY 2001 and FY 2010 rose to $615 billion in constant 2013 dollars (see Figure 1.2 above).

From an institutional perspective, the Defense Department had enormous capacity to raise funds, attract talented planners, recruit forces, and provide long-term training and career mobility. Defense budgets were spent heavily on weapons systems manufactured and forces deployed in the United States, creating close links between the services and American industry, leading to President Dwight Eisenhower’s warning about the risks of “unwarranted influence” by the military-industrial complex. US global military presence was rationalized into regional combatant commands (Watson 2010). The Defense Department created a miniature State Department in 1977, the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, to handle strategic planning, policy development, and international negotiations on military issues.

As this evolution of the military institutions proceeded, the services and the Office of the Secretary of Defense created and institutionalized programs and activities beyond the core missions of deterrence and military combat.7 To be sure, the military has long been involved in noncombat tasks, such as disaster relief, engineering projects, medical readiness exercises, and humanitarian and civic assistance (Graham 1993). But the scope and prioritization of these noncombat activities changed over time.

Starting in the 1980s, for example, the military extended its activities into counternarcotics operations and the Congress formalized authority for the ongoing military practice of conducting humanitarian activities (Serafino, Chapter 7).

The 1990s saw an even more significant expansion in the noncombat tasks assigned to the military. The United States has a long tradition of deploying military assets to deliver humanitarian assistance in response to earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes, and other natural disasters, but these deployments increased after the Cold War (Cobble, Gaffney, and Gorenburg 2003). Troops were sent to provide humanitarian assistance to the Kurds in Northern Iraq, to Somalia, to parts of the former Soviet Union, and became involved in stabilization and reconstruction efforts in Bosnia, Haiti, and Kosovo.

US policymakers and military leaders were initially cautious about the “mission creep” involved in these operations. They saw such missions as secondary “military operations other than war” (MOOTW). The deployments were meant to be brief: US leaders remained reticent to take on the complex roles of long-term institution building and development (Zinni and Koltz 2006; Priest 2003).

Eventually the Clinton administration came to believe that US policy and programs for postconflict reconstruction needed to be more formalized to produce sustained results, including an active role for the military in the promotion of the administration’s strategy of engagement abroad. While the initial US troop commitment to the NATO-led Implementation Force (IFOR) in Bosnia and Herzegovina did not extend to law enforcement activities, the US troops committed to the subsequent NATO Stabilization Force (SFOR) became more involved in restoring public services, economic reco...