![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

American Strategy in the Indian Ocean

ANDREW C. WINNER AND PETER DOMBROWSKI

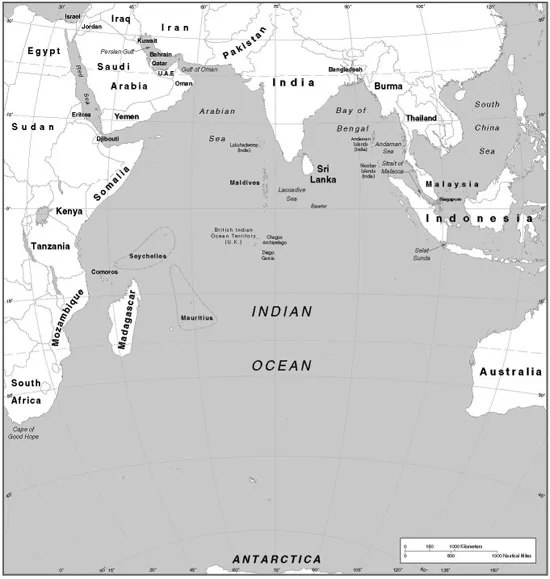

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest ocean in the world. Its littoral consists of forty-seven countries, and several strategically important islands are contained within its boundaries. Access to the Indian Ocean is controlled by nine passages, of which five are key sea lines of communication (SLOCs) used to transport energy.1 By some accounts nearly 40 percent of the world’s energy supplies are either found in the Indian Ocean proper or pass through the region from the Persian Gulf to Europe and Asia. The Indian Ocean links the thriving economies of Asia as well as the mature economies of Europe with the carbon-rich fields of the Middle East and the raw materials of Africa. It also connects the vast manufacturing capability of China with the wealthy markets of Europe. The Middle East is China’s largest source of oil, and Beijing’s dependence on oil imports is only slated to grow—to 75 percent of its total oil requirements by 2035. Almost all of this oil will cross the Indian Ocean.2 This increasing dependence of China on the importing of oil and other hydrocarbons is a central factor in the large and growing percentage of the world’s energy, raw materials, and general merchandise trade flows that cross the Indian Ocean. In sum, the Indian Ocean has replaced the North Atlantic as the central artery of global commerce. Therefore, external security threats or internal disruptions in the Indian Ocean region could have serious implications for many countries and the global economy as a whole.

The Indian Ocean is also becoming, once again, a distinct and increasingly important geographic space as well as a potentially contentious political arena.3 China’s political and military interests have expanded apace with its economic growth and commercial reach. For the first time in the modern era Chinese naval vessels are patrolling the western reaches of the Indian Ocean. Chinese corporations, including some with close ties to the Beijing government and all with diplomatic support, are investing deep inside Africa, not to mention ports and other infrastructure in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and beyond. India has watched each Chinese move with suspicion while remaining cautious of American overtures toward establishing greater bilateral political and military cooperation. Meanwhile, third parties from the Indian Ocean and beyond—from Australia to Japan to several European states—continue to maintain a presence in the region or are in the process of expanding previously limited roles.

The United States therefore needs to strongly consider whether to develop a strategy for how it is going to pursue and protect its interests in this distant maritime region. The rise of the Indian Ocean as an artery of global commerce and its potential as a venue for geopolitical conflict raise questions about whether, and how, American policymakers should adjust their previously limited approach to the region. The premise of this book is that a US strategy for the Indian Ocean is necessary, and the authors of the volume’s chapters outline various potential strategic approaches. Before the United States decides whether to develop a distinctive regional strategy for the Indian Ocean, key questions must be answered:

• What exactly are the US interests in the Indian Ocean region?

• What are the key geopolitical characteristics of the region, and how are they evolving?

• How can the United States increase its leverage to protect and advance its national interests in the region?

Such questions are not new or unique to the United States and its regional strategies, much less to any potential approach to the Indian Ocean. But they are the basic questions that underlie the grand strategies of the great powers that are seeking influence around the globe.

This introduction first reviews the concept of the Indian Ocean as a region. It then summarizes US engagement in the region, including how American national interests may be placed at risk by current developments and/or benefit from policy, political, or organizational adjustments. It then considers how different grand strategic frameworks can help scholars and policymakers alike think through the pros and cons of differing approaches to the region. It then argues that by exploring the costs and benefits of the full range of strategic approaches in the context of the specific regional challenges and the constellation of political, economic, and security interests of both regional powers and extraregional powers, the United States can identify a strategic approach to the Indian Ocean region that provides influence within the bounds of fiscal, operational, and geopolitical constraints. The chapter concludes with short overviews of alternative American strategies toward the Indian Ocean, developed by the chapter authors and drawn from the community of scholars and policy professionals who are actively engaged in debates over the future of US strategy.

THE INDIAN OCEAN AS A REGION

For the purposes of this volume, the Indian Ocean is considered as having the following geographic scope: South Africa to Australia, including all subordinate bodies of water (e.g., Bay of Bengal, Arabian Sea, Red Sea), exclusive of the Southern Ocean. The question of whether the Indian Ocean should be understood as a tightly integrated whole or as a set of interlocked subregions is left to the analyses of the individual chapter authors within the context of their specific strategic foundations. At this point it is sufficient to recognize that the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea, and so forth present unique maritime topographies and operational challenges with often quite distinct histories, traditions, and political structures.

The Indian Ocean is an unusual geographic space to discuss as a formal, or even emergent, region for a number of reasons:

• The notional Indian Ocean region differs from other geographic spaces commonly studied by many strategists in that its core is not a continent or even a closely linked set of territories and islands (e.g., Oceania) but rather a large body of water constrained on three sides by continents.

• Regional conflicts have not been rare; but even the most intense among them—the wars between India and Pakistan—have been contained. They have not, as yet, threatened global peace or spread widely, although with the emergence of openly declared nuclear weapons states and the increased activity levels of Chinese military forces in the ocean, escalation may be possible in the future.

• Superpower competition in the Indian Ocean was anticipated in the 1970s and 1980s, but it never materialized in any significant way before the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War.

• The security challenges most commonly associated with the Indian Ocean region are either sea based (piracy, proliferation, and trafficking) or land based, but with a significant maritime dimension (terrorism).

However, the Indian Ocean is an interesting and important, if not necessarily critical, theater for the United States for several reasons:

• As Robert Kaplan suggests in his recent book Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power, there is a possibility that the Indian Ocean will develop into a fully fledged region complete with self-identity and mature political, economic, and military institutions.4

• If the Indian Ocean does develop in ways that approximate the institutional dynamics and long-term evolutionary characteristics of other classically defined regions, such as Northeast Asia and Western Europe, it will in all likelihood do so because one or more outside powers, such as the United States and/or China, help by expending political capital, material resources, and diplomatic skills in ways that may or may not be welcomed by the countries in the Indian Ocean littoral.

• If the United States attempts to exercise regional leadership alone or in tandem with another power such as India, the primary instrument of American statecraft will, in all likelihood, be military and especially the so-called sea services—the US Navy, US Marines, and US Coast Guard.

• The Indian Ocean may soon emerge as a zone of conflict between the world’s lone remaining superpower, the United States, and its emerging challenger, China.

• The interactions of four (and possibly more) nuclear powers in the Indian Ocean (India, Pakistan, China, and the United States) as well as several other states with modern, high-technology military forces (e.g., Australia) make the stakes for promoting regional peace and stability exceptionally high.

This section is organized into two subsections. The first considers whether the Indian Ocean can be considered a “region” and, if it is, examines the specific nature of the region. The second explores challenges to American interests in the Indian Ocean and whether meeting these challenges requires a comprehensive regional strategy. The subsections support arguments that are central for the rationale for undertaking this volume: (1) The Indian Ocean is an emerging region within the globalized economy and security architecture; and (2) the emergence of the Indian Ocean as a region for purposes of strategy development is largely dependent on external factors, specifically the posture of the United States military and associated diplomatic, political, and economic activities.

Defining the Indian Ocean Region

The recent past aside, historians and geographers remind us that the Indian Ocean has long been a region, at least if we focus on the organizing principles of governance by third parties entering into and controlling large swaths of the Indian Ocean littoral. Both Western and Asian empires have used the Indian Ocean to construct interconnected trade and migration networks with land-based enclaves, cities, and military installations.5 From the West successive waves of Portuguese, Dutch, French, and British governments and commercial enterprises have used the seas to spread from the Middle East and Africa across the Indian subcontinent to Southeast Asia and eventually beyond. Various Arab empires and the Ottoman Empire also controlled swaths of the Indian littoral and commercial routes over the centuries. From the East, Chinese private traders searched far and wide for high-value commodities and, for a brief period at least, the Ming dynasty sent a “treasure fleet” under Admiral Zheng. He sailed across the Indian Ocean in search of diplomacy, trade, and exploration.6 In each case, people, economic activities, languages, customs, and culture spread in ways that continue to tie peoples separated by thousands of miles.

Currently, with the exception of a small number of forward-thinking commentators and strategists in the United States and India, few think of the Indian Ocean as a single region.7 In academic terms the Indian Ocean and its environs have witnessed very little of the regionalism or regionalization that has characterized South America, Africa, and East Asia, much less Europe—the case that has generated much of the theorizing and empirical research associated with the problems of “regions” in an increasingly globalized world.8 Economic flows—from trade to investments—occur largely cross the Indian Ocean, that is, for example, from the Persian Gulf to China, or head out of the region, for example, from India to Europe—from one country or subregion to others: “Almost three-quarters of the trade traversing through the Indian Ocean, primarily in the form of oil and gas, belong to states external to the region.”9 In short, the bottom-up commercial connections said to drive regional economic integration are limited, despite the importance of the Indian Ocean to the functioning of the global economy.

As for regionalization, there are few regionally based economic, political, or military institutions active in the Indian Ocean that focus exclusively on the problems, and much less the potentialities, of the Indian Ocean’s geography. Even one major counterexample—the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium—is of relatively recent vintage and has to date focused only on discussing a limited number of maritime security issues, what some strategists call “low-hanging fruit.” The impetus for this symposium came largely from the Indian Navy, an institution whose worldview is somewhat different from, and perhaps ahead of, those of many Indian politicians and bureaucrats and, perhaps more tellingly, that of the dominant Indian strategic culture.10

Scholars have speculated that India’s own distant maritime past, combined with the national growing and globalizing economy and the maritime exploits of China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy, might stimulate the emergence of a “seaward worldview” in India.11 This in turn might eventually lead the Indian government to promote a more coherent and institutionalized “Indian Ocean” region. In the short to intermediate terms, however, this remains an aspirational vision of some maritime-minded Indian strategic and military thinkers. A careful assessment of Indian military thought and capabilities suggests that the Indian Navy, Air Force, and Army can and will continue to undertake power projection operations in the region, even given the Ghandian origins of Indian foreign and security policies; but it is less clear whether these activities will be in the service of broader regionalization or indeed provoke it in response.12 Further, the United States, on its own or in careful and tentative partnership with India, might ultimately provide the impetus for regionalization.

India has the size and potential to emerge as a global economy player, but it is not yet there. The US Central Intelligence Agency estimates that in 2012, India possessed the world’s fourth-largest economy measured in terms of purchasing power parity, and that it has been growing at roughly 7 percent a year for the past three years. But India has yet to emerge as a major trading partner—in 2012 it ranked twenty-first and ninth, respectively, for exports and imports. Much of that trade is not with other Indian Ocean littoral states (although India is becoming a larger petroleum refiner), but the refined products are often then exported to states outside the Indian Ocean region. In other words, the integration of the Indian Ocean region through regional trade does not seem like it will be a driving force supporting regional institutional growth.

With one notable and short-lived exception, third-party great powers have not been especially active or engaged in the region as a whole since World War II. The exception is a short period at the height of the Cold War, when Soviet naval deployments briefly preoccupied American policymakers, in large part because of fears that naval operations were a prelude to, or could support, overland moves on the oil-rich Persian Gulf.13 As a result of this concern, coupled initially with the British withdrawal from Aden in 1967 and, in 1979, with the Iranian Revolution, the United States took steps to increase its military presence in the region as well as its ability to rapidly reinforce the Persian Gulf region.

The lack of strategic rivalry by the great powers could change as China begins to view the Indian Ocean as essential for its own security. One survey of China’s maritime activities observes that although China’s officials claim that its activities in the Indian Ocean are peaceful, “the development of military maritime infrastructure in the Indian Ocean would provide China access and a basing facility for conducting sustained operations and emerging as a stakeholder in Indian Ocean security architecture.”14 Some American national security analysts view China’s activities, particularly as capabilities grow, as inevitably posing a strategic competition to the United States.15 The increase in India’s military capabilities that has accompanied its two-de...