![]()

Part I

The Strategic Perspective and Players

![]()

1

The Third Sector

Society consists of the private sector, the public sector, and the nonprofit sector, sometimes referred to as the “third sector.” Organizations in the third sector often pursue educational, health, cultural, religious, artistic, political, charitable, philanthropic, or other social goals. They seek to serve the public at large (such as the disaster-relief efforts of the Red Cross) or the public good of a narrowly defined membership (such as a home owners’ association or country club). Their aims often support the most noble features of society.

Nonprofit organizations (or “nonprofits”) fulfill a unique role in society. They differ from business in that they do not seek to maximize profits. Their aims follow from their mission to serve the public good; activities are not constrained or prioritized on the basis of their profit potential. Moreover, surpluses are reinvested in the organization rather than distributed to corporate owners. Nonprofits also differ from public organizations in that their activities are not subject to processes of democratic governance. Nonprofits often take over where inadequate political will exists, such as providing additional support for the arts or education that includes religious elements. In recent years, nonprofits are also used by governments in helping to implement public policy, such as by providing services to special populations.

Nonprofits also stand on their own, regardless of the distinctions among the three sectors. Nonprofits are often unique in the values they adopt and the passion with which they operate. For example, many nonprofit schools commit to educating the child as a whole, rather than only focusing on narrow, academic skills. Some focus on helping the child perform in a web of social relationships, whereas others emphasize moral development or self-esteem. They may have a secular or religious base. Likewise, environmental organizations are often passionately committed to preserving nature as their first priority, leaving it to business and government to balance other priorities. Nonprofit organizations operate under their own set of values and have their own ideology with which they pursue their goals. Although many private and public organizations seek to make the world a better place as a part of their efforts, nonprofits tend to be strongly driven by the values embraced by the organization.

Knowledge about the third sector is fundamental to understanding the broader society in which we live. It provides contrast between the governmental and for-profit sectors; it reflects the emergent and ongoing concerns of society; and it often serves as the springboard for social change in local, national, and international arenas. Historically, many successful local and societal issues initially championed in the nonprofit sector have gained support and eventually developed considerable implications for government and business. Examples include compulsory free public education, workers’ compensation, social security for elderly citizens, birth control, animal rights, pollution control, and scores of other issues. The emotional, in-kind, and financial support of those concerned are often sufficient to create a nonprofit organization that serves as a platform for the group’s concerns. The third sector also provides nonprofits with shelter from the profit motive of business and the limitations of democratic governance. Starting in the nonprofit arena, ideas and causes need neither government support nor profitability to survive.

On the surface, many activities of nonprofits seem similar to those of business or government. After all, providing health care services or kindergarten through 12th-grade education are found in each of the three sectors. So why single out the management of the nonprofit sector for separate consideration? Is there not one best way to provide these services? The answer is a resounding “no.” The way that services are provided inherently reflects the purposes of organizations, its leadership, and constraints that characterize their environment, causing for-profits, government, and nonprofits to act and react differently.

The Strategic Approach

To understand nonprofits, their leadership, and their constraints, this book argues for a strategic approach that views nonprofits from a broad perspective and asks such questions as, What is the nonprofit trying to achieve? What are the expectations of constituencies that support a specific nonprofit? What strategies are available to the nonprofit? What roles do leaders play? What resources does the organization have to support its aims? Surely, then, there is a need for understanding how successful nonprofits attain success, but “best practices” are only one of several factors that shape how nonprofits accomplish their goals.

The strategic viewpoint that underlies this book focuses on the “why, what and how” of organizations. When we asked nonprofit directors these questions as we prepared for this book, most responded by talking about the activities their organization performed, whether it was feeding the homeless or providing funds to other nonprofits. Certainly, understanding the day to day activities of a nonprofit is essential because these activities ultimately justify its existence. But before there was activity, the creators of the nonprofit had an idea that served as the central organizing principle, the reason they and others were willing to devote time, effort, and other resources to creating the nonprofit. That central idea—such as feeding homeless people—becomes the basis for people to rally in support of the nonprofit. The key question is “Why should anyone care about this organization?” (McLaughlin, 2000). Although a vision statement inspires, a mission statement defines the scope and purpose of the organization. It seeks to answer the question, What is the purpose of this organization? It defines the core activities of the organization and its aims and further carves out the scope of the organization. Finally, the organization develops a strategy, which defines how it will attain its vision and mission. An effective strategy ties together the competencies of the organization in a way that enables it to effectively and efficiently achieve the mission. It seeks to answer the question, How is the organization going to go about achieving its purpose? (McLaughlin, 2000).

The vision, mission, and strategy of an organization constitute a strategic approach that guides leaders, staff members, volunteers, beneficiaries, donors, and other constituents in understanding the goal, scope, and direction of the organization.

Benefits of a Strategic Viewpoint

Why is a strategic viewpoint necessary? Understanding nonprofit organizations from a strategic framework offers several benefits. First, it provides a unifying theme around which the many activities of the nonprofit can be understood and interpreted. It serves as a shorthand explanation of the nonprofit without becoming bogged down in details unique to different organizations. Whether recruiting staff, donors, volunteers, or board members, a strategic perspective provides the basis for informed commitment among the nonprofit’s various constituents by addressing “Why?” “What?” and “How?” Simply put, the strategic approach summarizes the most compelling arguments for involvement and support (Sheehan, 1999).

Second, a strategic viewpoint offers guidelines for action. The vision, mission, and strategy serve as templates against which operational and fundraising plans are evaluated. Will specific actions move the organization toward its vision? Which decisions best support the mission? Do action plans fall within the nonprofit’s strategy? Why should one course of action be preferred over another? Agreement about the strategic elements is more likely to make decisions and actions a source of unity among internal constituents (such as management, staff, and volunteers) and reinforce a consistent picture among external supporters (such as potential board members, donors, funding agencies, and allies).

Third, as explained more fully in later chapters, virtually all nonprofits form alliances among private, public, and other organizations. The ability to gain assistance of other organizations is often essential to a nonprofit’s success. Without clarity of vision, mission, and strategy, it is difficult to discern which relationships are important and for what reasons. More compelling, unless the nonprofit can clearly articulate its niche, potential allies may be uncertain, and therefore reluctant, to assist the nonprofit.

Fourth, a strategic approach forms the basis for evaluating the nonprofit. Is the nonprofit doing a good job? Is the executive director effective? Are constituents being effectively and efficiently served? As will also be developed more fully in later chapters, nonprofits (by definition) do not have profits by which to gauge their success. Likewise, they are not subject to voter approval, as is the public sector. Instead, an assessment of the nonprofit must evaluate its vision, mission, and strategy. Without these strategic benchmarks, board members, outside supporters, staff, and volunteers have little against which to compare results. Because nonprofits often depend on the goodwill of their supporters, being able to demonstrate effectiveness becomes increasingly crucial for nonprofits that wish to grow and prosper (Greenfeld, 2000).

Limitations to a Strategic Viewpoint

The strategic perspective has limitations. First, developing a strategic approach may not match the desires of the leadership (Clolery, 1999). Some nonprofits, particularly small ones, operate opportunistically. That is, revenues are raised, resources are committed, and programs are undertaken based on current possibilities—independent of any grand or strategic design. This opportunistic culture is much more common among newly formed nonprofits or nonprofits that have a strong, founding leader. Some founding leaders view the nonprofit as their fiefdom. Those that do often do not see the need for a strategic approach. In fact, they may view mission statements and strategies as limitations on their freedom to act. Often this view is reinforced among board members who are selected for their support, friendship, and philosophical agreement with the founding leader. Though such nonprofits would benefit from a strategic approach, as a practical matter opportunistically run nonprofits seldom change unless there is a change in the leadership or the organization faces some crisis.

Second, a practical limitation is resources. Developing a strategic approach and following through takes time and resources. Not convinced of the value behind a strategic approach, it is difficult to get boards, leaders, and senior staff to devote the energies needed to create and operate from a strategic perspective.

Third, a strategic approach may assume a degree of sophistication that the nonprofit has yet to attain. Expecting a nonprofit to develop sophisticated vision, mission, and strategy statements that serve as the templates for its actions and evaluation may be unrealistic initially. Newly formed nonprofits, much like new businesses, need time to determine their niche, expertise, and support. Prematurely locking the nonprofit into one direction or another may cripple or even destroy the organization’s potential. Understanding the stages of development among nonprofits gives insights about the internal and external characteristics associated with different levels of maturity and sophistication.

The Life Cycle of Nonprofits

Not only do nonprofits vary by vision, mission, and strategies, they exist at various stages of development. Like people, organizations move through a life cycle as they mature. Each stage presents different challenges—some of which are opportunities and others of which are threats. How a nonprofit navigates these stages shapes its effectiveness and determines its very survival. This navigation of the maturation process takes place in many ways and on many levels. Two important dimensions are the strategic and operation levels.

Strategic Nonprofit Evolution

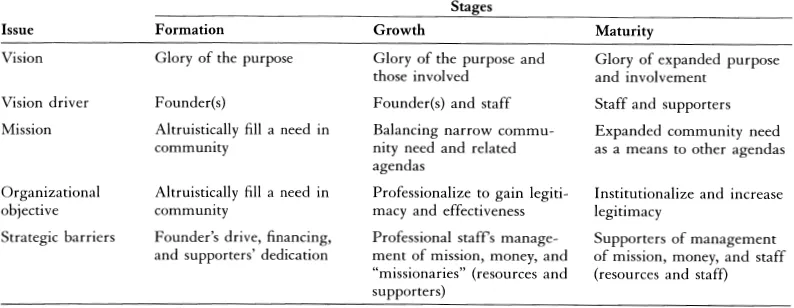

Table 1-1 uses a three-stage framework: formation, growth, and maturity. Within each stage, the relevant issue evolves. This evolution is neither systematic nor uniform. Nonprofits proceed at different rates and in different ways. Some organizations will move rapidly from formation to growth to maturity on one issue and lag behind on another. Except at the very beginning of a nonprofit’s existence, it is not unusual to expect one to have characteristics associated with multiple stages as some issues mature and others remain unchanged.

Vision Driver

A vision statement is an ennobling, articulated statement of what an organization is and what it is striving to become. It answers the questions of what the world would be like if the mission were attained. The vision of the nonprofit typically reflects the glory of the purpose at the formation stage, but evolves to embrace key constituents. As the nonprofit gains success and matures, the vision may be expanded to a larger purpose or domain. This expansion typically reflects the organization’s growing success and the pressures placed on it by internal constituents (such as managers, professionals, and staff) and external forces (such as funding sources, clients, board members, community expectations). Although the founder or those involved in the formation stage may view this expansion of the vision as desirable, they may also see it as a dilution of the organization’s original mission. Although changes or expansion of the vision may be essential to the ongoing viability of the organization, such changes can be the basis for schism among supporters and staff.

The vision driver is typically the founder or founding group. With greater maturity the vision becomes increasingly institutionalized and is increasingly driven by staff and supporters and less by the founders. In time, the vision drivers give way to professional leaders, who add their beliefs and expectations to the interpretation of the vision and the mission. Professional, nonprofit managers typically bring with them a more systematic approach to the leadership of the organization. Sometimes this transition may substitute systems and efficiency for the zeal and passion of the founders. Improved accountability also may be injected into the vision of the organization, because founders typically focus on outcomes rather than internal processes.

Table 1-1Nonprofit Evolution at the Strategic Level

Mission

The mission of most nonprofits typically is to fill a need in some defined community in an altruistic fashion. With growth of the organization comes a greater need to balance the needs of the beneficiaries with those of the larger community. The introduction of professional management complicates the mission by adding the personal needs and aspirations of managers as another element of the organizational mission. At the mature stage, nonprofits often expand the needs to be met through more complex agendas. Moreover, the success of a m...