![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Organizational Perspective on Rules

The organizational perspective on rules derives from a half century of organization theory. At the broadest level of abstraction, rules are the means by which organizations channel individual energy into collective goals, whether that is simply to survive (Merton 1940), manage size and complexity (Dobbin et al. 1988), reduce cognitive uncertainty (March and Simon 1958; Cohen and Bacdayan 1994; Cohen et al. 1996), imitate peers (Dimaggio and Powell 1983), or evolve into new and improved versions (Nelson and Winter 1982). More concretely, organizations use rules to achieve specific purposes (Cyert and March 1963), such as the ones that will be examined here. While these functions apply to public and private sector organizations alike, they are particularly critical for delivering public goods and services and symbolizing public values.

While this claim may seem hopelessly rational in a postbureaucratic world, it actually refers to a bounded form of organizational rationality that social scientists have recognized for many years. Nobel Prize winner Herbert Simon observed in the late 1940s that organizations strive for rationality but never quite get there. Organizational rationality is highly imperfect and far from providing the crystal clear goals, complete information, and exhaustive evaluations required to make optimal decisions (1947). Simon’s version of organizational rationality is bound by the finite processing capacity of the human brain, by hazy goals with incomplete information, and by tactics that pass only minimal, not optimal, standards (79–80). From Simon’s perspective, organizations pursue rather than perfect rationality, and rules are one vehicle for this pursuit.

The idea that public organizations use rules is not just theory; it is evident in the findings of the Local Government Workplaces Study. On the whole, cities and counties write rules to accomplish a variety of objectives: to control costs, protect citizens, and develop employees, to name a few. Beyond the managerial objectives that rule-writers have in mind, rules fulfill broader functions that enable goal-oriented action: coordinating, constraining, and empowering employee behavior; socializing employees to organizational values and norms; creating, storing, and disseminating knowledge; and conveying legitimacy to external stakeholders. Public organizations use rules to accomplish each of these functions, though none are accomplished perfectly.

The Written Rule and Organizational Rationality

Not all organizational rules are written, and organizations will vary in the ratio of written to unwritten rules (DeHart-Davis, Chen, and Little 2013). This variance notwithstanding, it is unwise to underestimate the power of the written rule for enabling the pursuit of rational organizational action. The advantage of having written rules is easily obscured in much contemporary public management discourse in which government is viewed as inherently inefficient and (as George Frederickson and colleagues put it in 2015), “the devil is bureaucracy” (112). Understanding the role of organizational rules in informing rational action requires a consideration of the written word itself and the ability of humans to put pen to paper.

Three aspects of organizational rationality—awareness of time, access to knowledge, and abstraction—would be difficult to achieve without the written word. Organizational rationality requires the ability to measure and track time so that the past can be understood, the future can be envisioned, and the present can be controlled. Rationality also demands abstraction, the ability to categorize people, places, and things for broader understanding and control. Rationality necessitates knowledge of goals, tactics, and potential outcomes to inform decision-making. Prior to the Greek invention of alphabetic writing in the seventh century BCE, dimensions of rationality were circumscribed by a world that communicated exclusively through the spoken word and thus lacked the means to delineate time, the ability to think abstractly on any significant scale, or the capacity to store knowledge in a permanent way (Goody 1986; Havelock 1986).

Equipped by the written word, organizational rules enable rationality by shifting authority from the individual to the organization. Max Weber made this argument in the early twentieth century when he observed that a new kind of organizational form, the bureaucracy, was “capable of attaining the highest degree of efficiency and is in this sense formally the most rational known means of carrying out imperative control over human beings” (Weber 1947, 337). It is not that Weber loved bureaucracy or believed his model to be reality versus prototype (though he has been accused of doing so; see Leivesley, Can, and Kouzmin 1994); he himself admitted that modern life creates a structure from which escape is difficult (Weber 2012, 203). Rather, Weber’s point is that the legal authority that spawns bureaucracy is the only one capable of vesting power in something other than the individual.

To understand Weber’s thinking on rationality, one must understand his interest in sources of authority, or “domination,” as he indelicately called it (Bendix 1977, 292). Weber observed that people have legitimized authority systems in very different ways throughout history. This legitimacy enables those with power to secure the voluntary cooperation of the ruled, making their compliance something that is good and expected. Three sources of authority surfaced for Weber: charismatic, traditional, and legal-rational. With charismatic authority, the leader’s personality entices people to obey based on the belief that their leader is magical and obedience will yield good things or the avoidance of bad things—think Hitler, Ghandi, or Churchill (Dow 1969). Traditional authority involves inherited power being passed down generationally through bloodlines, such as in kingdoms or the mafia (Hummel 2007, 79). This inherited power is fixed and sacred and presumably derived from divine law. Taking a current example, if Prince Charles abdicates the throne of England, the crown will pass from his mother, Queen Elizabeth, to Prince Charles’s son, Prince William.

Rules and bureaucracy enter in via Weber’s picture of legal-rational authority, the third source of domination. Legal-rational authority is based in the law and rules that arise out of the twin systems of capitalism and democracy. Capitalism demands efficient administration as a means of maximizing profit (Weber 1946, 223); democracy requires the leveling of the governed (226). The development of this legal authority marked a major shift in the locus of power from an individual—whether magical or predestined—to an inscribed system. As a result, Weber’s bureaucracy is impersonal in comparison with the highly person-focused charismatic and traditional form of authority. This shift—from the personal to the impersonal—enables organizations to pursue collective goals that transcend the whims of the individual leader.

Weber has been criticized for being unduly optimistic about the merits of bureaucracy. The criticism is somewhat overblown: Weber simply observed the benefits of bureaucracy compared with charismatic and traditional authority systems. Consider the relative ease of establishing goal-oriented behavior in a bureaucracy versus attempting the same within a kingdom or a cult, where objectives depend on the whims of the king, the pope, or a shaman. In each of these cases organizational behavior is not driven by a collective goal but rather by the hopes, desires, and fears of a single person anointed either through his or her bloodline or by magic, not merit. Weber’s take on bureaucracy can best be described as “it is what it is,” which allows us to see the role of rules in rational behavior.

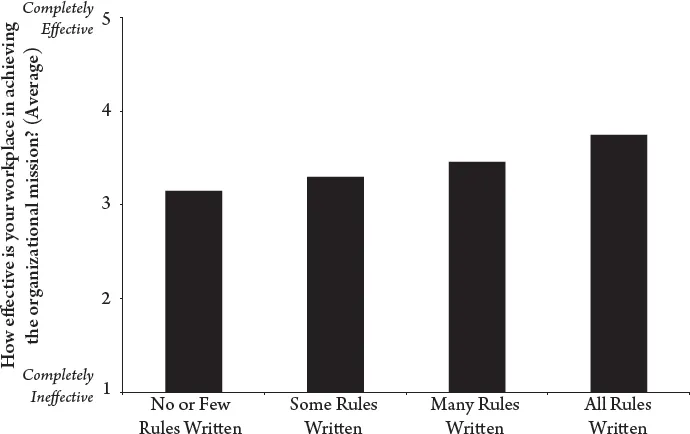

Evidence of the relationship between written rules and rationality is demonstrated in Figure 1.1, which compares employee responses to two questions from the Local Government Workplaces Study: How effective is your organization in achieving the organizational mission? and To what extent are rules in your workplace written? (The local government’s mission statement was included with the first question.) Mission effectiveness is used here to measure organizational rationality by capturing notions of an overarching purpose being pursued by the organization with more or less success. Survey respondents indicating no written rules or few written rules in their workplaces indicate a 3.15 out of 5 for mission achievement. By contrast, survey respondents who indicate that all of their organizational rules are written give their workplaces a 3.75 out of 5 for mission achievement. This statistically significant difference lends credence to the notion that putting rules in writing increases an organization’s capacity to achieve its mission.

Figure 1.1Rule Formalization and Workplace Mission Effectiveness

Source: Local Government Workplaces Study, Local Government Organizations 8 and 9, n=460.

Coordination

Organizational rules coordinate the behavior of large numbers of employees to behave consistently and cohesively on the organization’s behalf (March and Simon 1958; Stinchcombe 2001; Mintzberg 1979; Blau 1974, 338; Galbraith 1977). The written quality of rules enables this coordination by providing a focal point that both guides the behavior of employees across the hierarchy and reduces conflict about how things are to be done (Becker 2004). Chung-An Chen and Hal G. Rainey provide evidence of the coordinating capacity of rules in their analysis of 2002 National Organization Survey data, in which personnel formalization (including written procedures, training, and job descriptions) correlates with teamwork among core employees. In a local government example, rules provide a template for high-dollar purchases, performance evaluations, and budget formulation, regardless of whether the department fights fires, bills residents for utilities, or transports citizens to and fro. In this sense organizational rules are like sheet music for an orchestra. One municipal fleet manager explains:

Our departmental policies are very clear. We have safety policies, we have employee work rules, we have operational procedures and processes. To get everyone on the same page, doing everything the same way, we’ve had to quantify a lot of different things, to deal with workplace issues or problems, anywhere from coming to work to how we interact with people, what we do and what we don’t do.

“Getting everyone on the same page,” as this manager suggests, involves using rules to create shared meaning (March and Simon 1958, 184; McPhee 1985; Chen and Rainey 2013). When public employees experience an organization’s rules, whether through compliance, enforcement, explanation, or discussion, they glean common understandings about both the rules’ purposes, requirements, and implementation, as well as the nature of the organizations for which they work. These shared experiences enable cooperation, as explained by organizational trust scholars Katinka Bijlsma-Frankema and Rosalinde Klein Woolthuis: “Besides providing a tangible set of rules that is often used as the basis of control, codified rules and systems can provide common ground on which former strangers can develop a more abstract feeling of sharing, on which trust and cooperation can be built” (2005, 269). The shared meaning created through rules can occur across organizations as well as within them. Applying this logic to interorganizational private sector partnerships, business professor Paul Vlaar and his colleagues argue that formalization can grease the wheels of collaboration by enabling firms to make sense of and effectively cooperate with one another (2006, 2007).

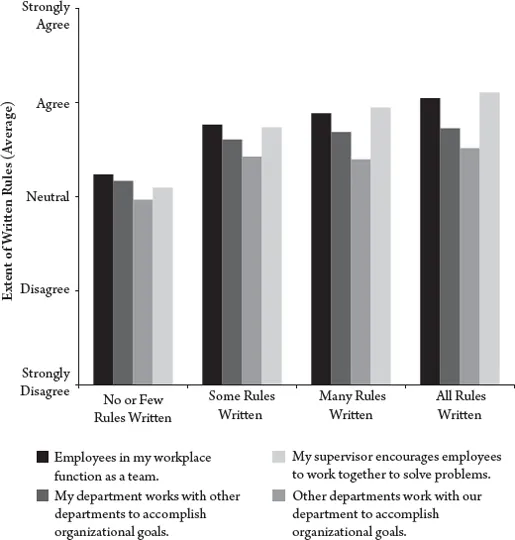

Figure 1.2 provides evidence of the sheet music effect of organizational rules. Based on survey data from Organizations 8 and 9 of the LGWS, employees perceiving higher levels of written workplace rules also indicate higher levels of teamwork, a finding consistent with Chen and Rainey (2013). The effect holds regardless of whether the teamwork occurs between or within departments. Based on this evidence, written rules appear to facilitate the integration of disparate organizational parts into a cohesive whole.

Of course, organizational rules can undermine coordination, particularly when they impose contradictory requirements based on conflicting values. The red tape literature cites this “negative sum compromise” as one precursor to the creation of ineffective or burdensome rules (Bozeman 1993, 286). Some North Carolina counties face this dilemma when they have two hiring systems, based on whether employees are covered or not by the North Carolina Human Resources Act (NCHRA). Employees covered by the NCHRA are entitled to procedural due process if they are fired, suspended, or demoted. But only county employees working in the departments of health, social services, and emergency management are covered by the NCHRA. Employees not covered by the NCHRA are at-will employees who can be fired, suspended, or demoted without procedural safeguards. Thus counties must track the personnel system under which each type of employee belongs and be prepared to impose a different system of rules with a different set of requirements and a different set of actors. The potential for conflicting personnel requirements has led some counties to consolidate and bring their own grievance procedures in line with state law, thus avoiding the potential for contradictory rules and the red tape they reap.

Figure 1.2Rule Formalization and Coordination

Source: Local Government Workplaces Study, Local Government Organizations 8 and 9, n=616.

Constraint and Empowerment

The notion that rules only constrain is a powerful myth; in reality, organizations use rules to both constrain and empower employees. While rules can no doubt excessively constrain, and on the whole perhaps constrain more than empower, they can also impose just the right amount of control and reap a host of benefits such as social leveling, trust, and procedural fairness, to name just a few (Olsen 2006).

Rules that constrain leave little room for discretion by specifying what can and cannot by done, by whom, and under what circumstances. By contrast, rules that empower give employees latitude in the decisions they make on behalf of the organization (see Box 1.1). Scholars have focused more on rule constraint than rule empowerment (Adler and Borys 1996; Clegg 1981; March and Simon 1958, 166).1 From the constraint perspective, rules are meant to minimize the uncertainty associated with human behavior (Merton 1940; Nelson and Winter 1982; Thompson 1961; Downs 1967). By eliminating this uncertainty, rules become “preformed decisions” (Kaufman 2006) or programs that trigger a “highly complex and organized set of responses” by specific “environmental stimuli” (March and Simon 1993, 162). Sociologist Alvin Gouldner coined this the “remote control” function of rules, allowing organizations to specify behavior across the farthest flung campus (1954, 166). Whether the rule requires letter-writers to use half-inch margins, purchasers to get five signatures, or fender-bending employees to take drug tests, rules tell employees what to do and when and how to do it.

Box 1.1Empowerment through Rules

Here is an excerpt from an interview with a public works director that illustrates the concept of empowerment through rules.

One policy change that I recently made delegates the authority to make adjustments to accounts. These adjustments were happening more and more and no one had a clear reason why or why not to do so. For example, there may be a billing error or we’ve done something causing the water bill to be high. Most of my staff wouldn’t adjust the bill; they didn’t want to get in trouble. Other staff members were adjusting bills liberally. But there was no paper trail and no oversight. I was getting more and more of these exceptions.

I can let staff do their thing, or I can get involved personally. So I created a new staff position that handles only requests for adjustments. This person has the ability to write things off. I don’t want to know about every one. And I documented this process in our policy manual. I put this change in writing as a financ...