![]() PART I

PART I

The American Constitutional Structure![]()

1

Federalism and Bioethics

Imagine that the national government passed a law that said, in effect, “Thou shalt not commit physician-assisted suicide.”1 At least one state—Oregon—already has a law that says just the opposite: in appropriate cases, it is very much okay to “actively” help a patient into the great beyond by prescribing a lethal dose of medication. How are we to decide which of these mutually inconsistent laws wins out?

It is these sorts of struggles between government behemoths that form the backdrop for much of the law relating to bioethics. Understanding how such struggles are resolved depends little on discerning which course of action is the best public policy—and even less on determining how best to protect a patient. The answer lies in working logically through the structure of this nation’s government. For readers with minimal or no background, this chapter provides a brief introduction to the somewhat dry subject of federalism.

As its very name demonstrates—the United States—our nation is structured as a union of distinct smaller units. The country is governed through a sharing of power between the national (also called the federal) government, and the governments of the individual states. Indeed, the word federalism itself refers to a governmental structure in which smaller political units come together and agree to give up some of their power to a centralized government. The framework for this sharing of power is the United States Constitution.

In allocating power between the national and state governments, the Constitution also indirectly plays a major role in providing power to a third group: the public. Often the Constitution will effectively deny certain powers to the national or the state government, or to both. For example, the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution notes that the “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” This makes explicit the concept that the United States government is one of enumerated (listed) powers: if a power is not mentioned somewhere in the Constitution, then the national government presumably cannot exercise it.

In point of fact, the Constitution grants a number of very broad powers to the United States government. Most of our attention, however, will be directed at the relatively few instances where the Constitution denies specific powers to national or state government. It is these denials that create individual rights, and effectively allocate power to the individual members of the public. Many of the issues that crop up in the study of bioethics relate to important aspects of people’s lives—issues turning on life, death, and reproduction—and these are exactly the sorts of rights created by the Constitution (and in some cases by state constitutions). To understand the law relating to bioethics, you must therefore understand the basic details of federalism.

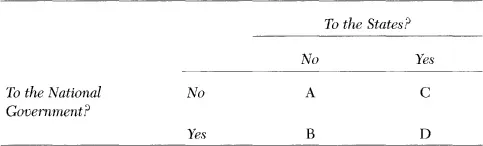

We should first note that there are four prototypical arrangements of power that may exist under the Constitution.2

How the Constitution Allocates Power

(A) Neither the national government nor the state governments may have been given the power to act in a particular area. Effectively, in such an area the people can do what they want. The classic “individual rights” created by the Bill of Rights—the right to freedom of religion, to name one—are good examples.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that denials of power are rarely absolute. On the one hand, the actual scope of the conduct protected by a particular right may be less than crystal clear. We have the right of freedom of speech, but that does not protect all speech. It does not give us the right to incorrectly shout “fire” in a crowded theatre. And some kinds of speech may be more protected than others (e.g., political speech v. commercial speech). Similarly, most constitutionally-created rights have definitional problems.

Assume in a particular instance that we are clearly dealing with conduct protected by a constitutional provision. A finding that a given law conflicts with such a “right” usually does not end the discussion. Instead it raises a second question: how important is the interest that the government is advancing, and how significantly does the law impinge on the individual right in question? Even constitutionally protected rights can be overridden. However, only extremely important government interests—often described as “compelling”—are likely to prevail in such situations, and only when the law is written so as to minimize its effect on the constitutional right.

Deciding whether the government interest or the individual right wins out is far from straightforward. An appropriate metaphor might be determining what gives when the hypothetical irresistible force meets an immovable object.

(B) The power to regulate an area may have been given solely to the national government. While Congress could enact laws to regulate such an area, state legislatures could not. Of course, the national government could also choose not to legislate in this area, which would effectively leave private conduct as free of regulation as would be the case under category (A).

(C) The power to regulate an area might be given solely to the states. This is the flip side of category (B). Any limitations on individual conduct in this area would depend on the state you are in, and whether that state has passed laws in that area.

Not that long ago, many would have said that few areas would fall into this category. Recent decisions by the United States Supreme Court have brought new attention to this category. Many now consider it one of the most important areas of constitutional law. Previously the power to “regulate commerce” was routinely accepted by Supreme Courts as giving Congress the authority to regulate things that the ordinary person would not view as having much, if anything, to do with commerce. Since 1995, the Supreme Court has dramatically rethought this issue, substantially cutting back on the power of Congress to use “the regulation of commerce” as a justification for its authority to enact laws. Charles Fried, former Solicitor General and retired federal judge, has described this general issue as follows:3

When, in 1995, the Supreme Court struck down the Gun-Free School Zones Act, which had been passed on the preposterous excuse that banning guns within 1,000 yards of a school somehow regulated interstate commerce, it made clear that Congress’s power over the country is not unlimited. Congress may not legislate just because something seems like a good idea; there must be a connection to one of the topics the Constitution entrusted to the care of the national government. And the claim that these topics are so vague that in reality Congress may legislate about anything at all was emphatically rejected.

A recent and dramatic example of this change in thinking is United States v. Morrison, 120 S. Ct. 1740 (2000). Christy Brzonkala claimed that while she was a student at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, two members of the football team raped her. After that attack, she was treated for depression and dropped out of school. During a school investigation, one of the men admitted having had sexual contact with her despite her having said “no” twice. He was initially suspended for two semesters, but on subsequent review by the school, his offense was recategorized as “using abusive language” and the suspension was set aside as being excessive.

Ms. Brzonkala then sued him and the school under the federal Violence against Women Act, which allows a woman to sue for money damages in federal court if she has been subjected to a gender-based violent attack. The Supreme Court determined that no provision of the Constitution—including the commerce clause—gave Congress the power to pass such a law, and declared it unconstitutional. As the dissenters to this 5–4 decision noted, the Court had in 1964 upheld the constitutionality of the federal civil rights laws on just such a commerce clause argument; it remained unclear why racial discrimination has a more obvious impact on commerce than violence against women.

(D) The national and state governments may have concurrent jurisdiction: they both have the power to pass laws in certain areas. Possible conflicts between these laws are resolved by the Constitution (Article VI, paragraph 2): “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof … shall be the supreme Law of the Land … any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” This “supremacy clause” assures that national laws will always win out in a battle with state laws. Often the hardest question, however, is determining what the state and national laws do in fact mean, and whether there is any conflict.

Finally, in addition to these four categories, it should be noted that even if the United States Constitution does not prevent a state from passing laws regulating particular conduct, the state’s own constitution may do so. It, too, may create individual rights that reserve powers to the people. If these rights are more expansive than those created by the United States Constitution, then that state constitution will effectively limit the powers wielded by its legislators.

To demonstrate the consequences of a particular issue ending up in one category as opposed to another, let us assume that Dr. X has been treating John Doe for end-stage AIDS. Both of them live in Oregon, where state law allows doctors to prescribe a lethal dose of medication for patients who request it. John is not complaining of pain but is disturbed by his growing loss of function: he is now blind, in addition to being bed-ridden and suffering from gastrointestinal difficulties as a result of AIDS-related conditions. John had concluded that his life “sucks big-time.” If he were rich, and had lots of servants to help out with day-to-day activities, he might find it minimally palatable. But given his current circumstances, and the minimal social services provided by the state, he has decided to ask Dr. X for the life-ending prescription.

We will assume that at the time of this scenario, there is a national law that criminalizes the conduct of a doctor who writes a prescription for a lethal dose of medication knowing that the patient intends to use it to end his life. Where does this situation fit in our categories?

There is a possibility (admittedly slim) that John’s situation might fall into category (A), with both the national and state governments being denied the power to prevent him from getting the life-ending prescription. As will be discussed later, the Supreme Court has rejected a broad constitutional right to physician-assisted suicide. However, a number of the Justices have acknowledged that in the appropriate (relatively narrow) situation, a person might be able to demonstrate a constitutionally protected right to actively end his life. If John’s situation were found to be such a situation—if, perhaps, he was suffering in a unique manner for which existing forms of palliative care are inadequate, or if the wording of the national law inappropriately restricted his access to palliative care—then the national law denying him the right to the lethal drug could well be declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court. Each state would similarly be prohibited from enforcing against him any of their own laws that were essentially equivalent to the national law that had been struck down.

On the other hand, based on the language of the Supreme Court’s opinions about physician-assisted suicide (see chapter 11), it is plausible to conclude that John does not have any constitutionally protected right at stake. Were that conclusion made, we would not be in category (A). We might, however, be in a relatively rare category (C) situation in which power has been denied to the national government and given solely to the states. Here is Charles Fried’s comment on a similar scenario:4

So what in the Constitution makes doctor-assisted suicide any of Congress’s business? … Imagine a different Congress passing a “Right to Life Protection Act of 2003,” prohibiting any state from imposing the death penalty. How could that be defended? As a regulation of interstate commerce because some of the material used in carrying out an execution might have crossed a state line? … You need only imagine the speeches that many of those who voted for a [national law against assisted suicide] would be making if death penalty opponents tried to introduce the bill I just described, and you will appreciate what a travesty of federalism [a bill banning assisted suicide nationwide would be].

If this scenario were under category (C), the national law would be a nullity; state law alone would govern. In John’s situation, since Oregon allows Dr. X to prescribe the lethal medication, he would be permitted to end his life. On the other hand, were they in any state other than Oregon, Dr. X’s conduct would probably be illegal because all other states ban such conduct.

Finally, it is possible that our scenario will come not under category (C), but under category (D). Whatever the recent attention being paid to situations where the national government has acted beyond its powers, the category (C) situation is still relatively rare. National legislation in areas that have no obvious relationship to a specific purpose mentioned in the Constitution has been upheld far more often than it has been struck down as unconstitutional.

If our assisted-suicide case winds up as a category (D) situation, both the national and state governments have the authority to legislate in this area. Since the national and the state laws are clearly inconsistent, under the supremacy clause, the national law wins out. John would be denied access to the medication.

As this example demonstrates, federalism is a complicated concept—and its application can play a pivotal role in determining what governments can or cannot do in a particular circumstance. Problems logically arise before, and to some extent apart from, a full consideration of the ultimate policy issues relating to what we might want a government to do in a particular situation. We will be revisiting federalism issues throughout this book, especially in discussions of the right to privacy, abortion, cloning, and the right to refuse care. But virtually any topic in bioethics has federalism implications.

Endnotes

1. This circumstance is far from hypothetical. The Pain Relief Promotion Act of 1999 (H.R. 2260) passed by the House of Representatives included a provision that would make it a federal crime to prescribe a federally controlled drug for the purpose of assisting someone to end his life. The Senate Judiciary committee later approved a similar bill, but as of July 2000 the entire Senate had not yet voted on it.

2. Geoffrey R. Stone, et al., Constitutional Law, 3d ed., 154 (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1996).

3. Charles Fried, “Leave the Personal to the States,” New York Times (Oct. 29, 1999), A-31.

4. Ibid.

![]() PART II

PART II

Reproduction![]()

2

The Right to Privacy

Privacy would appear to be a relatively simple concept, understandable by even young children: “Leave me alone!” Yet in the realm of law and bioethics, it has taken on a life of its own, one very different from its usual meaning. How did this state of affairs come about? The landmark case is Griswold v. Connecticut, which follows. To make sense of Griswold, we must first delve more deeply into the thicket of federalism.

The first ten amendments to the United States Constitution, adopted as a group in 1791, are commonly referred to as the Bill of Rights. They embody some of the best-known and most fundamental freedoms in this nation:

freedom of religion (first amendment)

freedom of speech (first)

freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures (fourth)

the right to due process of law (fifth)

freedom from double jeopardy (fifth)

freedom from self-incrimination (fifth)

the right to trial by jury, with representation by counsel, in criminal matters (sixth).

When these amendments were first adopted, they were understood to apply only to the national government, not to the actions of the state governments or private individuals. And, as was noted in Chapter 1, the Tenth Amendment highlighted special concerns about the actions of the national government, noting that if a power was not specifically given to the national government, then it was reserved for exercise by the state governments and the public.

Thus, as of the beginning of the ...