- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cover Name: Dr. Rantzau

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cover Name: Dr. Rantzau by Nikolaus Ritter, Katharine R. Wallace in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Arthur Owens (aka Snow and Johnny)

I began my work for the Abwehr on January 1, 1937. I sat at a desk in Hamburg, looking over a pile of questionnaires and other papers in front of me; my assignment was to recruit as many agents as possible to assist the Luftwaffe Operations Staff concerning the British Royal Air Force and aviation industry, and I was close to losing courage. The fact is, I had no prior knowledge of anything of that nature. All my knowledge about aviation was based on two reconnaissance flights as an infantry observer in an old open-cockpit Bücker double-decker. All I knew about espionage came from reading spy novels.

I had never received any special intelligence training. My short period of service in the army in 1935 and at various headquarter units in the autumn of 1936 merely helped to refresh my military knowledge. Now, I was sitting in Hamburg without the slightest understanding of the unfamiliar paraphernalia surrounding me. Previously I had reported to my immediate superior at general headquarters, Lieutenant Commander Joachim Burghardt, chief of the Intelligence I Subgroup. He was a roundish little man with thinning dark hair and a rather long nose. He greeted me jovially and briefly explained the organizational setup of the subgroup, but then he passed me along to another salt and pepper, extremely reticent gentleman by the name of Major Hilmar G. Johannes (Hans) Dierks.

Dierks was a section chief in the Navy Intelligence Service. He showed me a narrow, almost empty office, said I was to call him if I needed him, took his leave with a slight smile, and closed the door behind him.

A table, two chairs, and an empty safe stood in my barren office. I sorted through the papers on the desk. Baffled, I looked at one sheet of paper, put it down again, and picked up another one. Letters, numbers, and incomprehensible words danced before my eyes. They did not make sense. Burghardt and Dierks, of course, had explained to me beforehand the organization of Subgroup I, Secret Intelligence Collection for Navy, Army, industry, and Luftwaffe; but no one in Berlin had given any details as to how and where this procurement was to come from. I was simply told it was now my task to recruit agents and to answer the pressing questions put to us by the Luftwaffe operations staff.

But what were those questions? Looking at the questionnaires on my table, I read the following: ABW, L I/6, Ast-W-haven, Nest-Bremen, Gkdos, urgent, airport and factory Speke, details about Stapleford … and so on—just a bunch of mysterious abbreviations, numbers, and figures.

So, there I sat without a clue about where to begin. I had no predecessor’s files relevant to my assignment. I did not want to go to Lt. Commander Burghardt. It was hardly his task to teach me the meanings of abbreviations and the like. I needed someone who had time and patience. I thought of the man with the somewhat faded blue eyes who had taken me to my office. Fortunately, I remembered his name among the many introductions to other employees. Somehow, I felt he was knowledgeable. I had just gathered up my courage to look for Dierks when the door slowly opened.

I turned around, and Dierks stood before me. “Well,” he said in his usual calm style, “are you making any progress?”

“What do you mean ‘are you making progress?’” I murmured. “I was just coming to find you.”

“I knew that,” he said quite casually. “Come on! Let’s go have a cup of coffee.” He pointed at the papers covering my desk. “Put that stuff in the safe and secure it.”

Vaguely relieved, I stood up and did as I was told. Then we went through the iron fence that separated our wing from the other military duty stations of General Headquarters; we passed the gatekeeper and the guard and walked into the street.

On the way to the little café around the corner, Dierks said in a rather comradely tone of voice, “In the first place they shouldn’t have had you come here at all. It would’ve been better if they’d run you first through the wringer for a couple of weeks in Berlin.”

“One fellow,” I replied, “a very distinguished looking older lieutenant colonel with a monocle, I forget his name, made a veiled reference to that also when they were shopping me around in Berlin. But the others thought I should first start in Hamburg, so they could report to Admiral Canaris that the slot had been filled.” At that point, I gave Dierks a sharp look. “They said, there are enough experienced people in Hamburg who could show me the works.”

“Well,” he smiled, “I’ll be one of them. By the way, the gentleman with the monocle you described, his name is Seber. He’s a very keen and unusual man. It’s a pity he’s assigned to work on matters concerning the East and not in your territory.”

So, we sat in the café, drinking a coffee spiked with some cognac. I used the occasion to take a closer look at my new colleague. He was the kind of fellow I would hardly have noticed under ordinary circumstances. Dierks was about ten years older than I and already had completely gray hair. He had a high, intelligent forehead, but his mouth was too narrow for his face, which, upon closer observation, actually seemed ugly but still rather sympathetic. Listening to him for some time and observing him, you would automatically have been captivated by his entire personality. Later on, I found out, to my genuine astonishment, that he had something that was extremely attractive to women, women of any age, any type, and any nationality. He told me that he was divorced and his young son spent one day with him each week.

Coming from a Friesian farm family, Dierks displayed the slow, contemplative style that characterizes the Friesians. Friesians think first and talk later. They do not speak any more than necessary. They rarely display any excitement.

Dierks had a brother who was a kind of clairvoyant, and he himself, as I learned later on, was the type who would run around with a divining rod. He had been a reserve officer in World War I and was in Intelligence even then. Although he had been in the insurance business before he joined the Abwehr, I always had the feeling he already worked for Intelligence in the Black Reichswehr. He was ever so knowledgeable, and like an old fox in this field. I could not wish for a better mentor.

Dierks gave me a detailed overview of our organization, its mission, its operating procedures, and its contacts. Sitting back at my desk, I was able to put some order to my stacks of papers with the hitherto incomprehensible hieroglyphs.

“And don’t think that somebody expects you to answer all questions right away,” Dierks counseled me. “Before you can actually get down to work, you have to find someone who will go to England for you and make inquiries there about places, factories, and other things. Since you’re an Intelligence officer, you yourself must never visit the country you’re working on. On the other hand, you can travel all over the world to find suitable people.”

“So, where am I supposed to start?” I asked, somewhat subdued.

“I’ve got one for you,” Dierks said. “He’s a Welshman who offered his services to our embassy in Brussels when I was stationed there.”

“Why don’t you keep him for yourself?” I asked.

“No,” Dierks said, shaking his head. “I can’t use him because he has more contacts with the Luftwaffe than with the Navy. I have his address and a few notes concerning him. You can start with that. As you’ll see, the notes will give you an idea of how best to contact him.” I was much delighted. This was a good beginning.

“And then,” Dierks continued, “go to the Chamber of Commerce, and talk to Mr. Lerner. He’s our contact man there, and you’ll certainly get valuable contacts through him. He knows all the importers and exporters who work with Scandinavia and England.” “And,” he added with his characteristic, barely noticeable smile, “do not exaggerate things, do not get nervous, and do not expect any immediate success in this type of business. And if you write letters, you might never get an answer. That calls for patience on your part.”

I thanked him. He had given me far more than I had ever dared hope for. Before Dierks left his office that same evening, he gave me the notes concerning the Welshman. His name was Arthur Owens. I gave him the cover name Johnny [Snow to MI5].

Johnny was an electrical engineer and ran his own little company with a workshop in England. Additionally, he was a representative of foreign companies, including the Dutch Philips-Werke. He was thus able to move all over the continent in an official capacity. During a business trip to Brussels, he had made himself available to the German embassy. He gave as his reason for wanting to help that he was a Welshman who hated the English and therefore offered to provide information on the British aircraft industry.

I pored over the notes concerning Johnny, and I kept wondering with growing excitement whether this Welshman might not become my first “spy.”

2

Dr. Rantzau

The next morning, I wrote my first letter to Johnny; I described a new type of dry battery and offered him a chance to import it into England. This was a battery built in Hamburg by a company that specialized in dry batteries and was owned by one of our trusted contacts. I indicated that, if he was interested, I would be happy if he would visit me in Hamburg. I signed the letter, which was written on company stationery, using the name Dr. Rantzau. That was a routine business contact for Johnny’s alibi.

After the First World War, I had studied business administration; I had been a mercantile managing director in both Germany and America and was familiar with international commercial practices. In civilian clothing, I was primarily considered to be a businessman, so my camouflage was genuine in every respect. We rarely wore our uniforms.

Our cars displayed ordinary license plates without any military symbols, and our drivers were civilians. Dierks was the only one who had his own car at that time. Whenever appropriate, I posed as a textile merchant. That was the field in which I was technically and commercially competent. But, because I spoke fluent English, it was also quite natural for me to act as an interpreter for Johnny and the technicians making the batteries. This was later also the case with other contacts.

There were four telephones on my desk; three were used exclusively for my various business contacts. When one of the managers picked up the receiver, he always used the company name, but everyone else had strict orders to only answer with the relevant number. In this manner, Dr. Reinhardt, Dr. Jansen, or whoever was requested, would be called to the phone. In any country where I happened to be traveling, I had other names, each with a corresponding passport. In Hamburg, I was Dr. Renken, an emissary of various German companies.

Over time, with the help of Mr. Lerner of the Chamber of Commerce, I established a series of solid connections with Hamburg companies, for whom I often acted as representative, and as assistant to the managing director, who happened to be traveling abroad. In that way, it was quite natural that on some occasions I would need to correspond with my agents on the respective company stationery displaying their unique business logo.

Gradually, I became familiar with the practical side of the Abwehr, with all of its nuances, subtleties, and wiles. In many cases, my education and my past civilian experiences constituted a foundation that was not to be underestimated, and without which quite a few connections and successes would not have been possible.

I had been brought up according to the strict Prussian principles of my father—obedience, justice, decency, and good manners. I was raised to be God-fearing and patriotic. Our motto was “One who is free, does what is right and strikes what is wrong.” I had been taught to believe every person was good. That rule, in my later life, constituted a heavy burden and was often sorely tried by my knowledge of human nature.

My father would have liked for me to study theology, but I always was inclined toward the military. I was an inspired soldier during World War I, before I had any concept of the dedication required by a military career and of my life in general. In the army, I quickly discovered that not all men were honorable and that I had to remain vigilant lest I be driven into the wall.

What had begun during my hardened soldiering days was now behind me in New York. My beginning in New York was a difficult learning experience. I found it most demanding to defend myself against the rudeness of the reportedly “nice” people. But I soon learned the key phrases, and my English vocabulary expanded with the addition of expressions that, to this day, I have not found in any dictionary.

In 1935, the German Consulate General in New York contacted me and asked whether I might want to become an officer again; so, I went to Germany, took an exam, and returned to the United States somewhat frustrated. The following year, General Friedrich von Bötticher, the military attaché in Washington, asked me to contact him. He shared with me that the Wehrmacht High Command, the Foreign Bureau, was interested in me. Well, that was more like it. In the meantime, the president of my textile company in New York had died, and the firm was now in other hands. That made it easier for me to make my decision. I accepted the offer and returned to Germany.

My new military career started in Bremen on September 1, 1936; from there, after a short time, I was transferred to the Wehrmacht High Command, Foreign Bureau–Intelligence I, under Admiral Canaris.

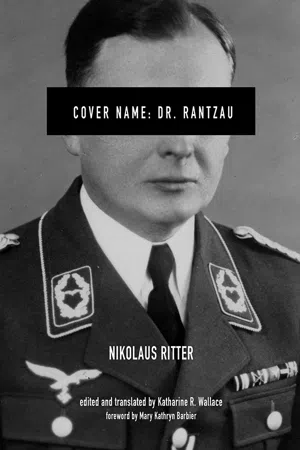

Nikolaus Ritter. From the editor’s private collection.

3

The Abwehr

I had never seen Admiral Canaris before I reported to him. I simply knew him from hearsay as the legendary chief of the Military Intelligence Service, the Abwehr; and I knew nothing at all about the Abwehr.

Secret intelligence is as old as history. The former German Intelligence was disbanded by the Allies after the First World War and was secretly resurrected a few years before Hitler took power. It was a powerful organization that developed gradually out of a small group that was originally affiliated only with Army General Headquarters. In the beginning, it engaged not simply in military affairs, but also in political intelligence; furthermore, it procured domestic political intelligence for the High Command of the Reichswehr.

After 1935, the political intelligence service was gradually removed and transferred to the SD [Sicherheitsdienst]. In 1938, after Admiral Canaris became Chief of Military Intelligence, he reorganized the Abwehr into three sections. Its activity was confined purely to military counterespionage and intelligence collecting.

The OKW [Oberkommando der Wehrmacht] Abwehr consisted of three departments:

• Intelligence I (Abw I)—foreign intelligence collection, espionage

• Intelligence II (Abw II)—sabotage

• Intelligence III (Abw III)—counterespionage

Departments were subdivided into four or five branches of the Wehrmacht: e.g., Heer (army, I H), Marine (navy, I M), Luftwaffe (air force, I L), and Wirtschaft (economy, industry, I Wi). In other words, I H, I M, I L, and I Wi and each branch of the service had further subdivisions, such as technical, communications, and Central intelligence (Z, the department for secret records...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Notes from the Author

- Introduction

- 1. Arthur Owens (aka Snow and Johnny)

- 2. Dr. Rantzau

- 3. The Abwehr

- 4. Launching a Network

- 5. Orders from Admiral Canaris

- 6. Departing for America

- 7. New York

- 8. Herman Lang and the Norden Bombsight

- 9. Contacts in America

- 10. Mr. X

- 11. A Close Encounter

- 12. Reconstructing the Bombsight

- 13. British Agents in the Abwehr

- 14. Lily Stein

- 15. Ein Glas Bier

- 16. Count László Almásy

- 17. Sabotage across Borders

- 18. Border Closings

- 19. Sea Rendezvous

- 20. Operation Sea Lion

- 21. Suspending Sea Lion

- 22. Africa Mission

- 23. Desert Devils

- 24. End of War

- 25. Reflections

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Nikolaus Ritter Military Awards, 1917–1945

- Glossary

- Selected Bibliography

- Index